During a campaign season in which climate change featured most prominently as a laugh line at the Republican National Convention, the low point was when CNN’s Candy Crowley addressed “all you climate people” in her explanation of why climate didn’t come up during the presidential debates. Who knew that human disruption of the global climate had become such a narrow, provincial concern?

But there’s important information in the fact that a senior reporter for a major network could dismiss climate change as essentially a special interest issue. It’s evidence, if more were needed, that “all us climate people” got our butts kicked in the battle for the narrative in the 2012 election.

And like the Republican Party, which is now undergoing the usual soul-searching that follows a big electoral defeat, those of us who believe that inaction on climate is the greatest threat facing our civilization (never mind the economy) have some serious soul-searching to do about our own defeat, which occurred long before any votes were counted.

Crowley’s explanation was consistent with the conventional wisdom on why the president didn’t make climate an issue. Because it was an “economy election,” and everyone in the D.C. press must accept that government action on climate change could do serious harm to the economy (because “it’s become part of the culture,” even if it’s not true), any discussion of climate policy by the president would have been off-message and worked against his chances for reelection.

The unconventional wisdom, popular among “climate people,” is that the Obama campaign failed to recognize the high level of popular support for action on climate change and missed a golden opportunity to seize a winning wedge issue when they chose the more politically expedient route of ignoring it.

There’s probably some truth to both of these explanations, but here’s a third one that is particularly useful in the context of a presidential election: The campaigns avoided talking about climate policy because they believed that raising the issue would be harmful in a few areas of key swing states that would likely decide the election.

Look, it’s tempting to point to all the national polls showing popular support for climate policy and say, “Climate is a winning campaign issue.” But a political strategist would find nothing useful in those polls, because campaigns are not won by appealing to the sentiments of the average American. Similarly, when a presidential candidate is speaking to a national audience, it’s easy to believe they are speaking to us — all of us. But they’re not. By and large, the candidates’ speeches are written to appeal to a handful of undecided voters in a few swing states, with just enough partisan red meat thrown in to motivate the party base to volunteer for the campaign and turn out to vote.

Americans understand that those swing areas are the “tail that wags the dog” of our national elections, but don’t necessarily think about the logical conclusion of that fact; the concerns and attitudes of swing voters in swing states are the “tail that wags the dog” of campaign messages, media coverage, and thus public understanding of which issues are important in the campaign.

The problem is, fossil fuel interests have figured out how to wag that dog. They know they can’t win public opinion nationally, but by focusing resources in key areas of swing states such as Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, they can frame the local discussion of climate policy and environmental regulations to their advantage (i.e., as a “job-killing war on coal”) and essentially neutralize those issues at the national level — at least during the election season.

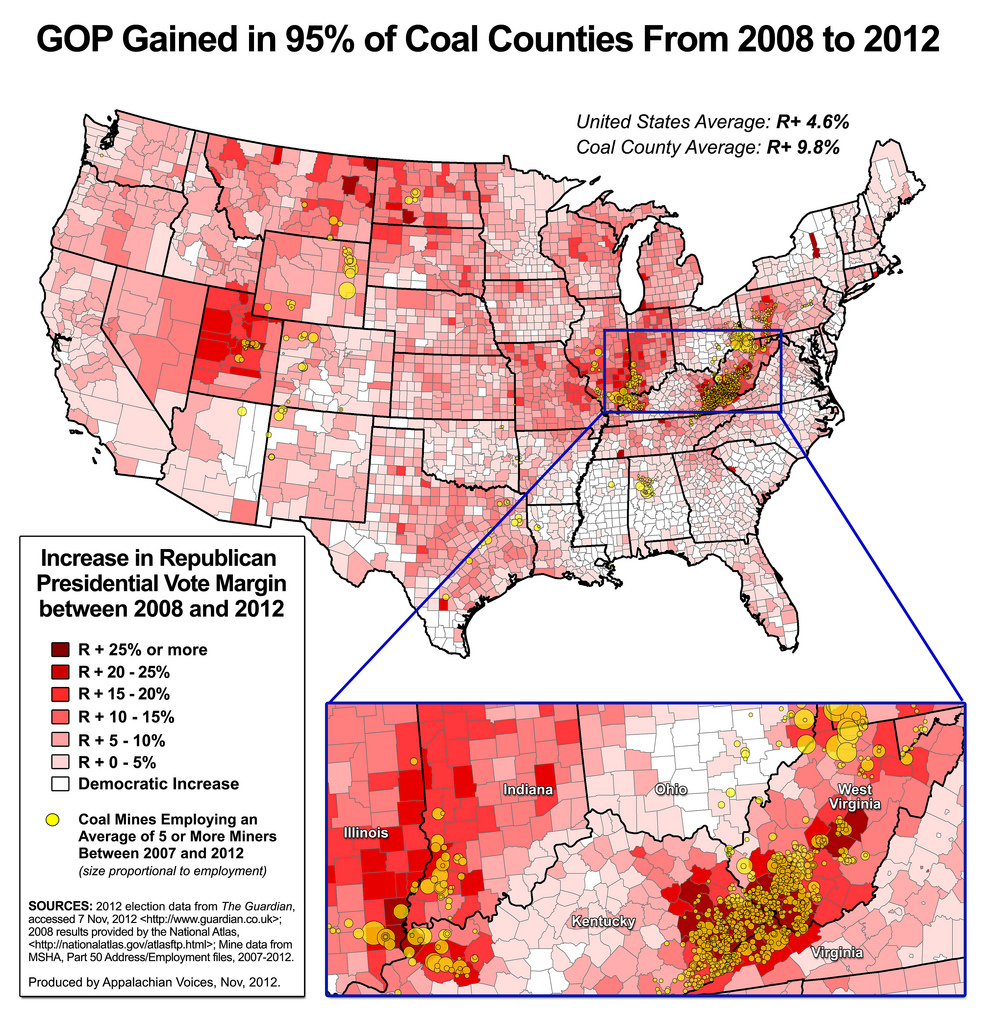

If the Obama campaign’s pre-election polling looked anything like the maps of election results in coal-mining regions of southwestern Virginia and southern Ohio, it’s easy to imagine strategists telling the president, “Don’t exacerbate this ‘war on coal’ thing or it could hurt us in swing states”:

Appalachian VoicesClick to embiggen.

This is the kind of map that pundits would be waving around if the election had gone the other way. The dark-red areas show the bleeding edge of the electoral and demographic movement toward the Republican Party that would have won the election for the GOP if those shifts had not been overwhelmed by pro-Democratic movement in other parts of the country. They also show where the Republican economic message of easing regulation was resonating with voters — as well as where Obama failed to win the union vote.

If Romney had won, it would be the rural, white demographic in coal-mining regions that would be the focus of the “how he won” stories, not the historic impact of the Latino, women’s, and youth vote. Pundits would be talking about how anti-regulation messages like “stop Obama’s war on coal” resonated with the electorate and how Republicans won a mandate to roll back environmental and public health regulations.

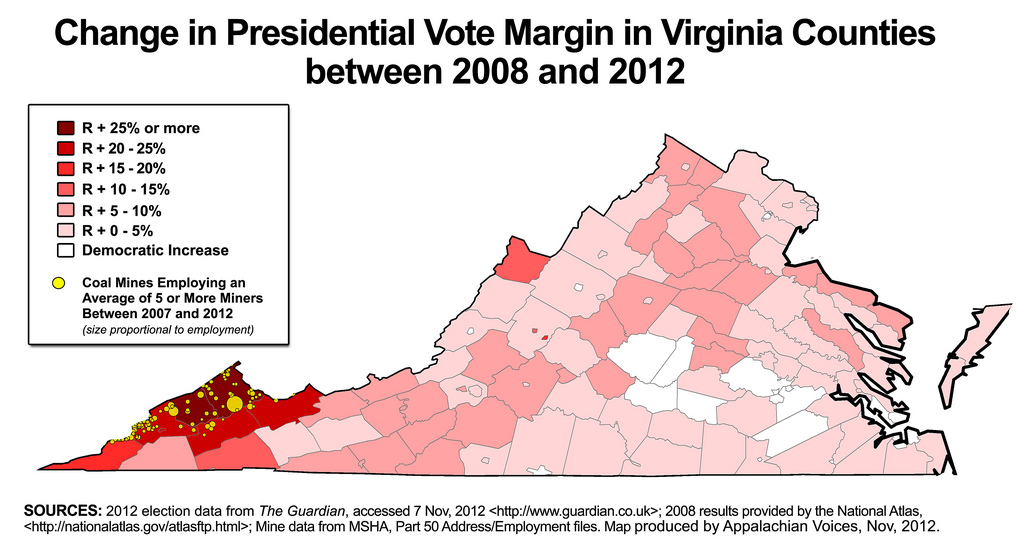

Exhibit A of that winning Republican strategy would have been Boone County, W.Va., which produces more coal than any other county east of the Mississippi River, and saw the largest pro-Republican swing (42 percent) of all 3,140 counties in the U.S. between 2008 and 2012. Of course, West Virginia is hardly a swing state, but the same pattern holds for southwestern Virginia, where the vote margin in the six coal mining counties swung in favor of Republicans by 24 percent — by far the best showing in a state that Romney barely lost:

Appalachian VoicesClick to embiggen.

Of course, some will look at maps of where Republicans made gains and say “So what? The Republican strategy failed.”

That is a fair point, from a purely political perspective. But there’s a lot of important information in these maps for those of who us aren’t concerned with electing Democrats, but rather with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, accelerating the deployment of clean energy solutions, ending mountaintop-removal coal mining, or all that and then some. They show the political price the administration paid for EPA’s actions to address greenhouse gas emissions, mercury pollution from power plants, and the impacts of mountaintop-removal mining on streams.

In other words, the maps demonstrate environmental and public health advocates’ collective failure to provide “political cover” in a politically critical region of the country for the EPA actions we demanded. They show why legislators tend to get defeated for supporting the issues we care about, and they help explain the embarrassing public displays of obeisance to the coal industry by politicians who survive, like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), who shot a bullet through the climate bill in a 2010 campaign ad, and Rep. Nick Rahall (D-W.Va.), who jumped out of an airplane in support of mountaintop-removal coal mining.

Nevertheless, as much as the coal industry would like us to believe that these anti-Obama voting trends are a backlash against the economic impact of EPA rules on hard-working people, there is simply no economic data to back that up. Mining jobs haven’t declined in most areas, even though demand for coal has dropped precipitously due to competition from natural gas.

The real reason for the pro-Republican swing is that coal industry-sponsored groups, with the assistance of billionaire-funded right-wing groups like Americans for Prosperity, were on the ground in coal-mining regions for the past three years holding rallies, putting up billboards, generating massive turnout to public hearings, and basically doing the kind of effective community organizing that is straight out of the progressive playbook.

As for what we can do better next time around, Bill McKibben got the soul-searching process for “climate people” going in the right direction even before the election was over, blaming our lack of progress on the fact that “we keep waiting for our political leaders to lead.” In other words, we need to stop worrying so much about what presidential candidates are or are not saying and get out and start building a movement of people talking about it to their neighbors, to their newspapers, and to their elected officials. That is exactly what McKibben is doing with his 20-city “Do The Math” tour that kicked off the day after the election.

But the lesson from the climate silence in the last election is that we can’t just build a movement in urban areas. We also need a ground game in the remote corners of swing states where national elections are won and lost, where campaign narratives are targeted, and where climate activists rarely tread. We need a strategy to provide key members of Congress and presidential candidates the kind of political cover that they need to support our issues without getting slaughtered in the next election.

It’s not as impossible as it might look from a LEED-certified, urban office building, because people in coal-mining regions care about the same things that people everywhere else care about. The difference is people in places like Appalachia have a stronger cultural and economic attachment to coal — one that the “agents of climate inaction” know how to exploit and that most environmental and climate advocates have no idea how to honor.

What coal companies and allies have done so well in mining communities is to frame every climate, public health, and environmental policy implemented by the Obama administration as part of a “war on coal” that threatens the economy of the region. However, if policies to protect clean water or stop the dumping of mine waste into streams are disaggregated from the “war on coal” frame, they’re actually nearly as popular in Appalachia as they are elsewhere in the country.

I haven’t seen any regional polls specifically about climate change, but I suspect we’d find a similar pattern revealing that Appalachians believe climate change is a problem and support action to address it. But people in mining communities are not going to support a war on coal, and the problem for “all you climate people” in breaking through the coal industry’s framing is that many of you actually do support a war on coal, or at least your rhetoric suggests you do.

That’s been particularly evident since the failure of the climate bill, when much of the focus of green groups and climate funders shifted to a strategy of “targeting” old coal-fired power plants for retirement. While there are certainly good arguments for why old coal plants should be retired, the public focus of big green groups on shutting down coal plants and their penchant for claiming credit for retirements that are the result of unrelated economic factors only strengthens the coal industry’s “war on coal” narrative and exacerbates the administration’s problem with swing-state voters.

Another reason that the organizing of right-wing groups like AFP has gone largely uncontested in coal country is a simple matter of resources. There are groups like Kentuckians For The Commonwealth that are doing extraordinarily effective organizing in regions where coal is mined, but when a group like AFP comes in with an $11 million ad campaign and bottomless pockets for on-the-ground organizing, we’re in the position of bringing a knife to a nuclear showdown.

Environmental and community advocates will never match the resources of the powerful industries they challenge, but the problem is particularly acute in places like Appalachia, where the big climate funders have largely turned a blind eye to the region. They have so far chosen not to support efforts to stop mountaintop removal and other egregious mining techniques, even though those are the issues that have proven to be effective in swaying public opinion and opening minds. In Appalachia, for instance, mountaintop removal and drinking water pollution are potent “gateway issues” that have inspired many residents to question the honesty and benevolence of the coal industry and their political allies in general.

But by far the most effective way to challenge the power of the “agents of climate inaction” in coal country is to enact policies to diversify the economy and build local support for clean energy industries. While a lot of resources have rightly been expended toward building the energy efficiency and renewable energy industries across the country, climate funders and big environmental groups have provided little if any support for economic initiatives to diversify the economy specifically in coal-dependent regions.

To make matters worse, local politicians in the pocket of the coal industry have shown little initiative in seeking to attract clean energy investments to the region, which puts coal mining regions at an even greater disadvantage.

The best thing that “all you climate people” can do to help break polluting industries’ grip on the tail that’s been wagging the dog of our national energy debate is to support policies to bring clean energy investments to coal-mining communities. Coal use is on the decline, but the political and economic power of the industry in the region where coal is mined has not waned — and won’t, until other industries replace it.

That’s not just good strategy, but it’s also the right thing to do. The communities that have supplied the brunt of America’s energy needs since the Industrial Revolution and powered our rise to be the greatest economy on Earth should not be tossed aside as we move toward a future powered by clean and renewable energy — they should be part of it. And the more we make them a part of that future, the faster we’ll get there.