In 1981, a Democratic president who’d made energy policy a centerpiece of his administration left the White House after just one term — voted out partly due to the perception that he didn’t do enough to combat inflation and high energy prices amid destabilizing conflict in the Middle East. His successor promised to open up the country’s oilfields and to “make America great again.”

It’s not exactly 1981 all over again, but today — as the country holds funeral services for Jimmy Carter, the 39th president, who died on December 29 at the age of 100 — the echoes of his term in office are loud enough to warrant taking a second look at how Carter’s presidency inaugurated the world we live in, one in which energy is central to American politics.

“From the minute he took office, Jimmy Carter made it clear that energy reform was top of his agenda. Literally,” the Princeton historian Meg Jacobs, author of the book Panic at the Pump: The Energy Crisis and the Transformation of American Politics in the 1970s, said in an email. “He got out of his limo during the procession to the White House, during the freezing cold, and watched the rest from a solar-heated viewing stand.”

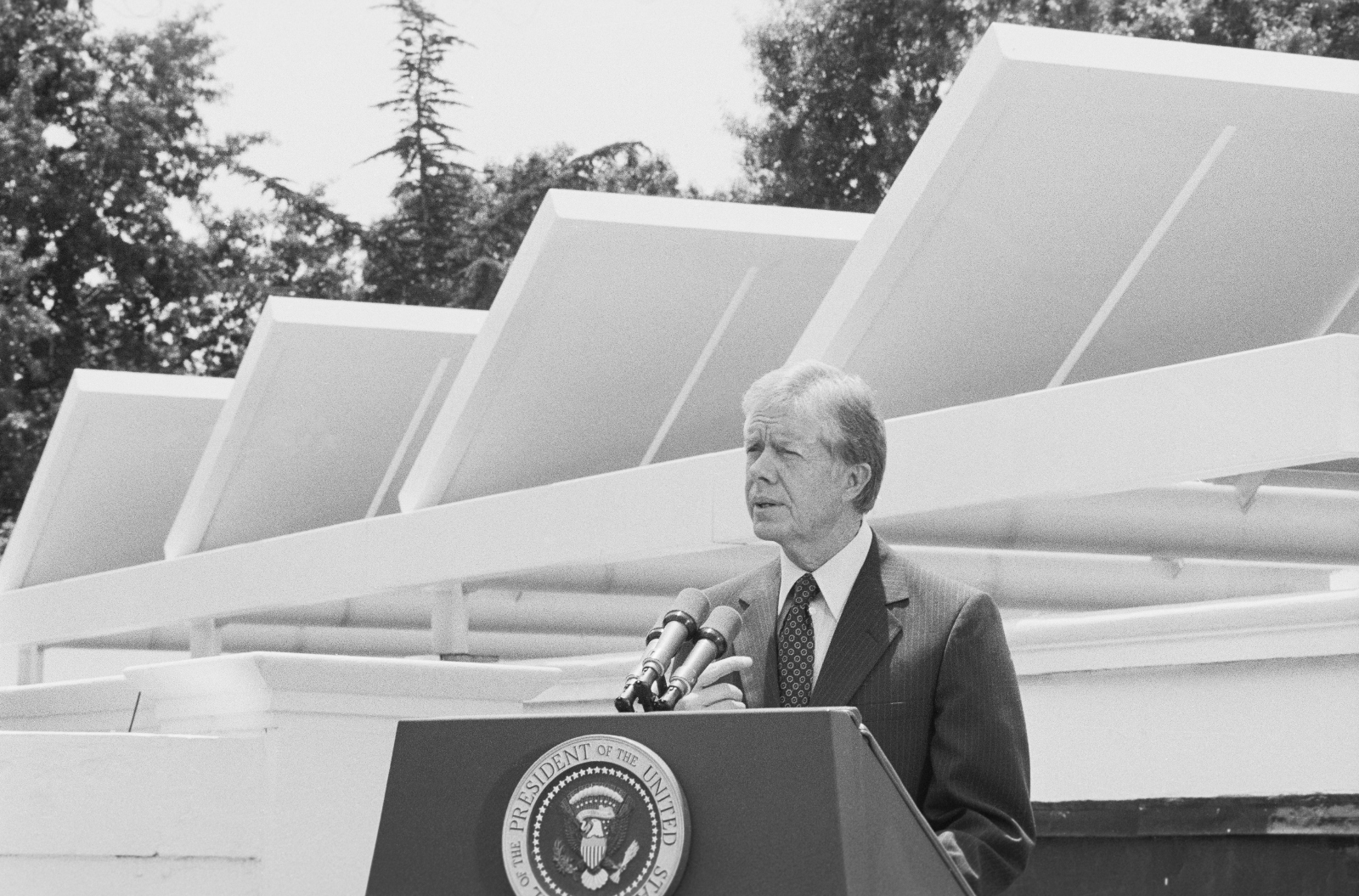

In symbolism and substance, President Carter displayed an obsessive attention to energy. He famously installed solar panels on the roof of the White House, but more consequentially, he created the Department of Energy, and allocated what remains a record amount of funding into energy research and development.

Carter’s energy policy had two primary objectives: reducing the U.S.’s dependence on foreign oil, and reducing its energy consumption altogether. The first goal has remained the watchword of the nation’s energy policy ever since. But the second, rooted in the Sunday school teacher’s conservationist and communitarian ethos, helped end his presidency — and helped convince future leaders that Americans’ refusal to be told to make do with less was an immutable political fact.

Carter’s attention to energy was the result of its appearance in the 1970s as a novel political problem. For most of the 20th century, the country had had little in the way of a coordinated energy policy, and the subject was far removed from political contestation in the public eye — even as the postwar American dream of car-dependent suburban homeownership was predicated on the assurance of oil’s eternal abundance and cheapness. The ’70s was the decade in which that promise started to crack up.

“By the mid-1970s, if you’re a middle-class working person who’s been encouraged to move to the suburbs and buy a V8 Ford or Pontiac, you’re structurally dependent on cheap oil and access to that oil for the reproduction of your everyday life,” said Caleb Wellum, a historian at the University of Toronto.

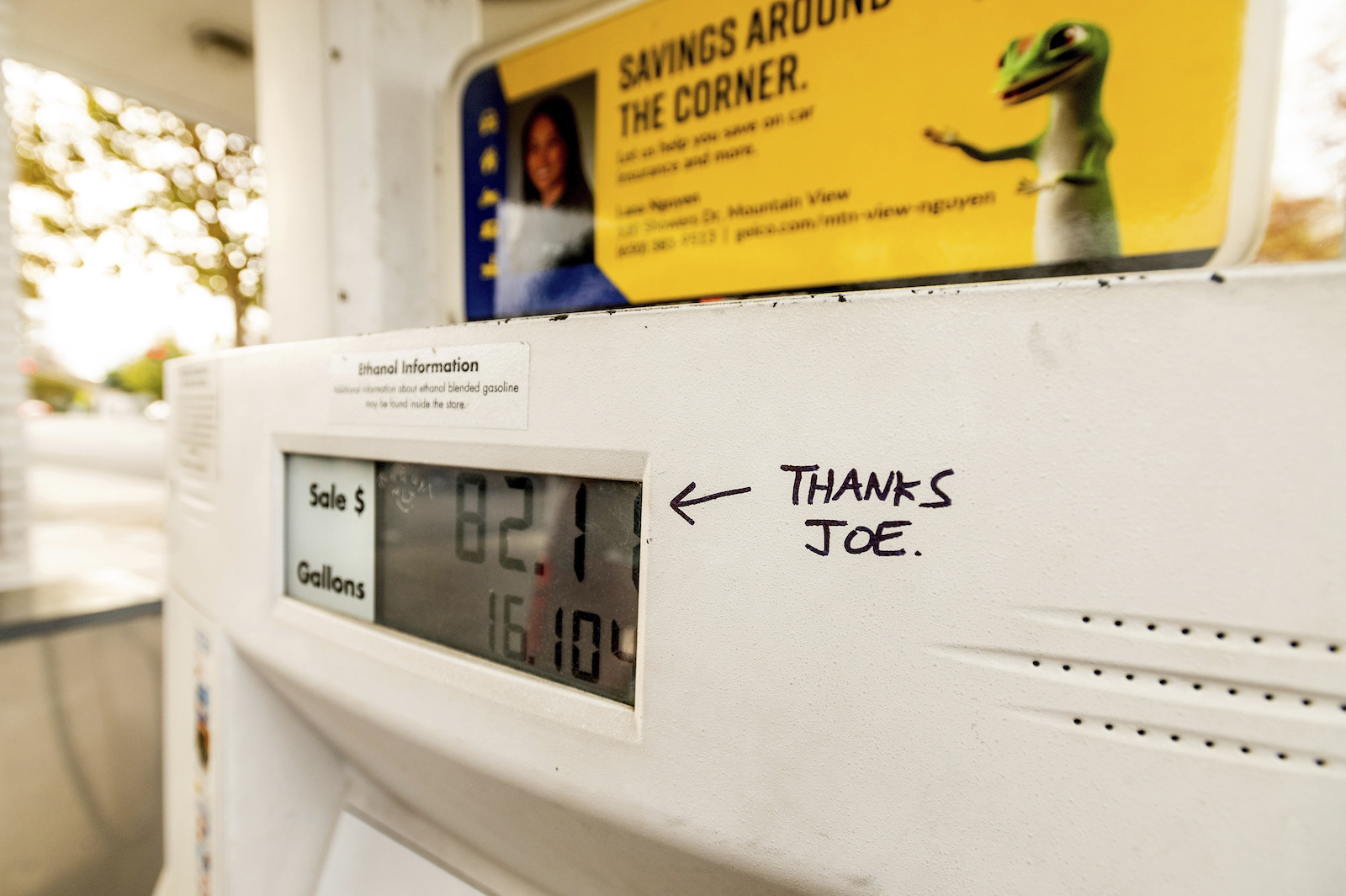

So it was a profoundly disruptive moment for the nation when, in October of 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries announced an embargo on exports of oil to any country that had supported Israel in the Six-Day War — catalyzing high gas prices in the U.S., lines of cars at gas stations stretching for blocks, and a years-long period of “stagflation” characterized by the demoralizing combination of high inflation, low growth, and high unemployment.

Besides the economic devastation it wrought, the embargo carried symbolic weight: “This comes after the Vietnam War, which was a blow to the collective ego of the United States because we had not emerged victorious. And then these nations that we thought were sort of our client states in the Middle East all of a sudden dictating to us about certain things. It was rather stunning at the time,” said Jay Hakes, the former administrator of the U.S. Energy Information Administration and director of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library.

The presidents who immediately inherited the situation, Richard Nixon and, upon his resignation, Gerald Ford, sought to remedy the situation primarily by expanding domestic energy production. But their focus on energy was less zealous than Carter’s — and far less visionary.

By the time Carter took office, on January 20, 1977, memories of the gasoline lines were already starting to fade. But with inflation and oil prices still high, and the U.S. still reliant on foreign imports of oil, Carter made it his mission to remind the country that it needed to think about energy. “A lot of his presidency was about convincing Americans that there still was an energy crisis even though the embargo was over,” Wellum said. “The conditions that the embargo had taken advantage of were still present, and the U.S. still had this problem it had to figure out.”

But Carter had a complex political coalition to wrangle behind his ambitions. The Democratic Party he led was split between two visions of how to address the issue: “You have the kind of old left, New Deal Democrat who is interested in protecting consumers, protecting the working class, and making life more affordable for more people, and that is in tension with the new left, environmentalist side of the left wing that’s questioning the ethics of consumption, saying that maybe oil is too cheap,” said Wellum.

On the other side of the aisle, animated by free-market economic doctrines then on the rise, was a Republican Party insistent that the gas shortages were “not a matter of scarcity but a matter of government overreach, bad government policy, and environmentalist overreach,” Wellum said.

The prescription, eagerly supported by the oil industry: “We need access to Alaska. We need access to the Outer Continental Shelf. We need to rethink how we restrict or regulate oil production,” Wellum continued. “If we do that, the free market and the oil companies and the American spirit will innovate and produce our way out of this energy crisis. We don’t need to consume less; we can have even more.”

This narrative was more or less anathema to Carter, who complemented his push for energy independence with an insistence that Americans do their part and collectively sacrifice for the nation. Clad in a cardigan, he addressed the country two weeks after taking office and implored Americans to turn their thermostats down to “65 degrees in the daytime and 55 degrees at night” to address the ongoing natural gas shortages.

At the same time, Carter was a contradictory figure who in some ways embodied aspects of each of the coalitions of his time — at once a big-government liberal and a deregulator; simultaneously the conservationist who fought the oil industry to preserve vast areas in Alaska and the energy hawk who expanded domestic coal production despite being aware of the science, already established, behind human-made global warming. “People often talk about Jimmy Carter the peanut farmer, but he’s also Jimmy Carter the nuclear engineer,” said Wellum.

In some ways, Carter’s economic policy marked the turning point toward the era of neoliberalism — a transition that Wellum argues in his book Energizing Neoliberalism: The 1970s Energy Crisis & the Making of Modern America was directly spurred by the oil crises of that decade. Driven by a belief in the efficiency of markets, Carter lifted the price controls on oil that Nixon had imposed in 1971 — a move characterized by critics at the time as a giveaway to the oil industry.

But Carter also signed the country’s first significant appliance efficiency standards into law, and invested unprecedented amounts of federal funds in energy research and development. These investments laid the groundwork for later breakthroughs, including the drilling technology behind hydraulic fracking, which enabled the U.S. shale boom in the 2000s. They also included a full-scale embrace of solar energy — a policy that, Hakes argued, “50 years from now, will be considered Carter’s major achievement.”

Carter characterized the nation’s need to secure and conserve its energy as the “moral equivalent of war” — a phrase derided in the press using its acronym, MEOW. The political problem was simple: “Hectoring the electorate in that way is not good politics,” said Wellum. Carter had already cemented the public image of himself as a preachy moralizer when things came to a turning point in 1979, with dramatic events in Iran.

After the Islamic Revolution, another symbolic repudiation of American global hegemony, came a second oil shock — and more gas-station lines, which Hakes argued may have contributed even more to sinking Carter’s reelection than the hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. “Carter’s poll ratings were lower in the spring of 1979 when we had the gasoline lines than they were later after the hostages were taken,” said Hakes.

It was a perfect opportunity for a presidential candidate whose message to Americans was that they could have everything they wanted.

“Reagan was the candidate who was optimistic about America, who would talk about how, if we can get government off your backs, we can liberate you ‘to do those things that I know you can do so well,’” said Wellum. “And Carter came across as this kind of moralizing guy, saying, ‘Americans have become decadent and no one’s listening to me.’”

In the presidential debates, Wellum said, “Carter emphasized conservation, and Reagan was emphasizing how we can restore abundant American production in the future, as opposed to a more efficient, environmentally friendly future.”

Reagan won the Electoral College by 489 votes to Carter’s 49. “At the popular level, that is a blow to the 70s as the environmental decade — the creation of the EPA, the Department of Energy, Earth Day in 1970,” said Welum. “There’s the backlash to that, the feeling that it’s anti-American, it’s anti-growth, it’s anti-freedom.”

The lesson was heeded by politicians of all stripes. Hakes, whose books on energy policy include The Presidents And The Planet: Climate Change Science and Politics from Eisenhower to Bush, said the word “sacrifice,” once a political cliché, almost completely disappeared from presidential speeches after Carter. Hakes puts this down partly to the fact that Carter was among the last presidents from a generation with a different attitude towards abundance and sacrifice. “The political leaders of that time generally had experienced World War II,” notes Hakes. (Carter was at the Naval Academy during the war and didn’t graduate in time to serve.)

But for a few decades after Carter’s presidency, energy conservation became a nonissue in U.S. politics. Due in part to Carter and Reagan’s policies, as well as European and Japanese gas taxes, the world became far less reliant on Middle Eastern oil in the 1980s. Oil prices tanked in 1986 and remained low through the duration of the century.

Needless to say, the importance of reducing oil consumption has since returned with a vengeance to the foreground of current affairs, fueled by climate crisis as well as new geopolitical conflicts. But we have yet to solve the issues that Carter confronted.

Within the climate movement, self-described “ecomodernists” argue that environmentalism’s legacy of conservationism is an albatross that permanently tars it in the public eye with the unpopular politics of austerity, while proponents of “degrowth” insist on the need to focus on reducing consumption. For socialist critics of the environmental movement, meanwhile, the ingredient missing from its ability to persuade people to take climate change seriously is a class politics, given the levels of money and power invested in the status quo.

“Environmental politics around energy, but also on climate, is really difficult to do, especially without some form of redistribution,” said Wellum — and the times feel bleak for those invested in this approach: “I’m pessimistic, or sad, that we don’t really know what to do around rethinking and reorganizing consumption, and the argument around redistribution seems even more in the wilderness,” Wellum said.

To Hakes, the apparent defeat of Carter’s approach is tragic. “If climate change is a problem, people should feel under some moral obligation: I will turn off the lights, or I will obey the speed limit because I know that my pollution will be a lot less, or I will go out of my way to buy the most efficient appliances and automobiles that meet my needs and I can afford. Or maybe I’ll walk a mile to pick up something rather than drive,” Hakes said.

“But politicians since Carter have not dared to say that, and maybe that’s a political reality we have to live with,” Hakes added. “One would assume that at this point people would say, ‘Our children and grandchildren deserve to have nature, and we shouldn’t be changing the environment pell-mell,’ and conservation would come back onto the agenda. I haven’t seen that yet. And I don’t even see seeds of that.”