This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

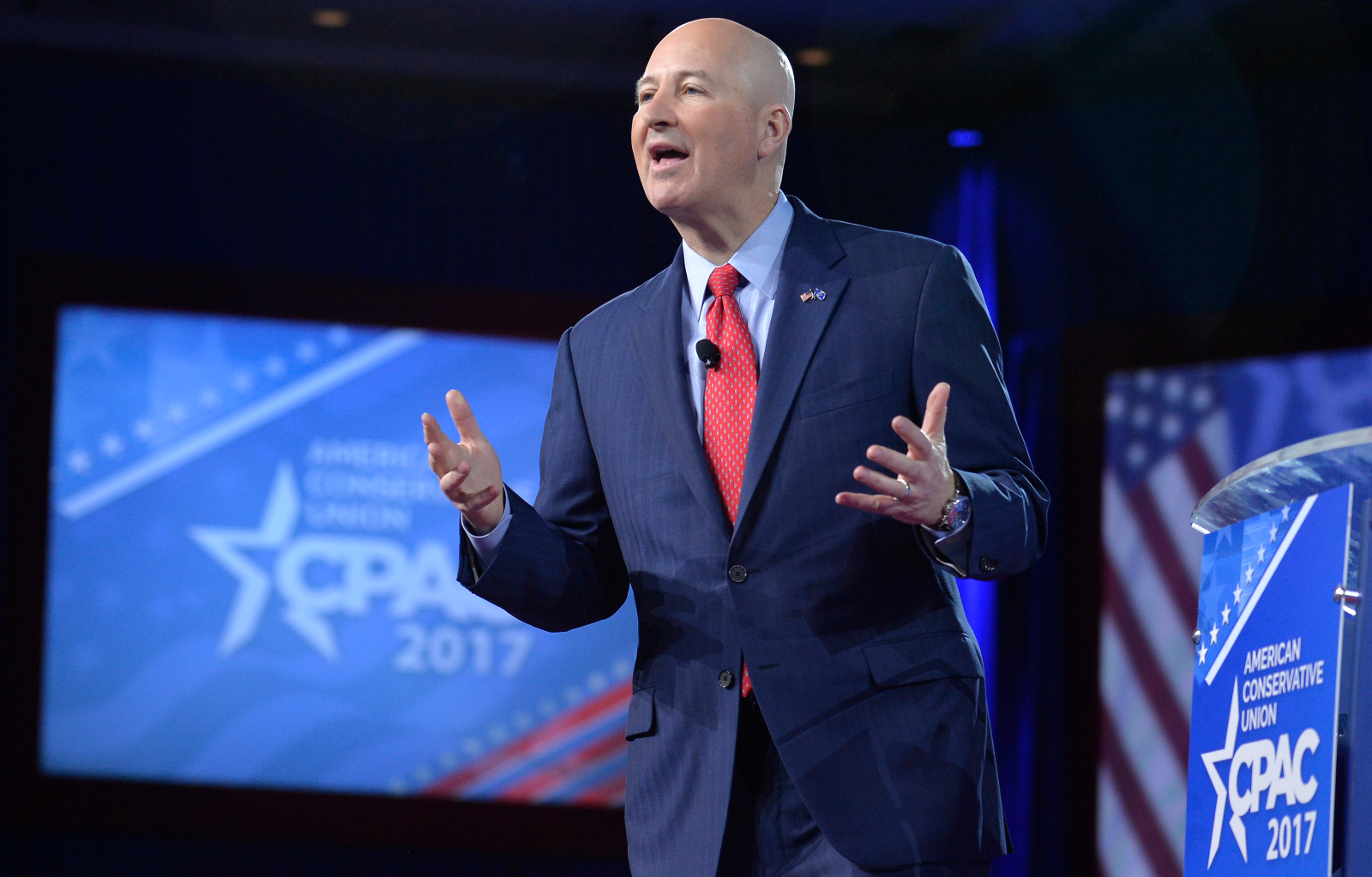

Earlier this spring, Nebraska lawmakers passed a bill authorizing construction of a canal that would siphon water from neighboring Colorado, igniting a war of words between the two states’ leaders. Nebraska’s governor, Republican Pete Ricketts, says that the canal will “protect Nebraska’s water rights for our kids, grandkids, and generations beyond.” Colorado’s Democratic governor, Jared Polis, calls the scheme a “canal to nowhere” that is “unlikely to ever be built.”

The two states share rights to water from the South Platte River, and Republican politicians in Nebraska say that a new canal is necessary to guard the state’s water supply from encroachment by its fast-growing neighbor to the west.

The strange thing about the political firestorm, according to water experts, is that the canal wouldn’t really do anything. The water Nebraska wants to protect doesn’t face an immediate threat from Colorado, and in any case it’s not clear the canal would provide Nebraska any additional water beyond what it already receives. The total amount of water that could flow through the planned $500-million-dollar canal is unlikely to change the course of either state’s future.

“It’s sort of a weird claim,” said Anthony Schutz, an associate law professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and an expert on water issues. “I’m not sure what exactly this thing would protect us from.”

Even if the canal doesn’t alter the balance of water between the two states, however, it does help Nebraska lawmakers spend down federal funding they received from the $1.9 trillion stimulus package passed by Congressional Democrats last year. It might also allow them to score political points by antagonizing the Democrats who govern Colorado. The episode comes as other parts of the western U.S. really do face wrenching, zero-sum tradeoffs in allocating water during an ongoing megadrought that has been exacerbated by climate change — and it may be a preview of how anxieties around those issues can be mobilized for partisan warfare.

The history behind the canal project is a curious footnote in the larger story of western water. Way back in 1923, Colorado and Nebraska signed a treaty that governed the use of one segment of the South Platte River, which flows from the Colorado Rockies through Denver and into Nebraska. The treaty required Colorado to send 150 cubic feet of water per second to Nebraska for the duration of the irrigation season—in other words, it prevented Colorado from drying up the river before Nebraska farmers could use it. The treaty also gave Nebraska the right to build a canal large enough to divert an additional 500 cubic feet of water per second during the irrigation offseason, but the project never came to fruition: Engineers had already tried and failed to build a canal through the rocky territory connecting the states in the late 1800s, and no one ever revived the idea.

For about a century, the treaty collected dust. Nebraska has perhaps the largest groundwater resources of any state, not to mention thousands of miles of rivers, so water wasn’t a huge issue. Plus, Colorado often exceeded its treaty obligations on the South Platte: From 1996 through 2015, the state delivered Nebraska almost 8 million more acre feet than it was required to deliver under the treaty. Around the same time, however, Colorado began drawing more from the South Platte to support booming population growth, primarily in the Denver area.

In January of this year, Colorado officials released an updated plan for the South Platte, outlining almost 300 possible water diversion projects along the river. This list of projects was just hypothetical, but it caught the attention of Nebraska lawmakers. Governor Ricketts released a statement saying he was “vigilantly watching” the construction of new water infrastructure in Colorado, and he told the legislature “they are trying to take our water.” Even though water from the South Platte is far from essential to the survival of Nebraskan agriculture, and even though Colorado already delivered far more to Nebraska than it needed to under the treaty, Ricketts insisted the state needed to protect its water rights from the growing liberal metropolis to the west.

“It’s a bit of a straw man,” Schutz, the University of Nebraska water law expert, said of Nebraska’s concern about the Colorado projects. “A lot of those projects that [Colorado] is proposing wouldn’t actually decrease the availability of water.”

Even so, the century-old treaty gave Nebraska the theoretical rights to build a canal of its own, and the state had plenty of money to pursue such a project. That was thanks to President Biden’s American Rescue Plan, which doled out billions of dollars of pandemic recovery aid to Nebraska and left the state with a significant budget surplus. The state’s unicameral legislature has spent most of this year’s session trying to find ways to spend down that surplus, and the $500 million canal project was a perfect candidate. The legislature passed a bill in April that allocated $50 million to start canal construction, enough to start purchasing land in Colorado and conduct preliminary designs.

The legislature’s sudden move on the bill came as a shock to water experts. As one Colorado water manager put it, “the water world was rocked” when the bill passed.

That’s because, according to Schutz, the very premise of the canal project is flawed. Ricketts argued that the canal would avert a “decrease [in] agricultural water supplies and [increased] pumping costs,” but neither scenario is in the cards, even if Colorado’s population keeps growing. Nebraska relies on groundwater for more than 80 percent of its farming irrigation, and the water that comes from the hypothetical canal would only arrive during the offseason anyway, so it wouldn’t help the state’s farmers. Meanwhile, the state’s water rights only cover one section of the South Platte, and Colorado has unlimited rights over a section of the river farther upstream, meaning the Centennial State can sustain future growth even without encroaching on Nebraska’s water.

Furthermore, Schutz says, it isn’t clear that there’s even enough water in the river to fill the canal, should it ever be built.

“If you look at the amount that’s coming in right now, that’s probably the maximum amount of water that we would ever get in the canal,” he told Grist. “And that is not a lot of water.” Not only that, but the treaty also only gives Nebraska the right to build a canal that can divert 500 cubic feet of water per second. It doesn’t actually give the state the right to that much water.

“From a political perspective, I think that the governor had to make Colorado into a bad guy, but then when you really get into the weeds I don’t know how bad of a guy Colorado is,” Schutz said, arguing that the state’s conservative government has been straining to find ways to spend away the federal stimulus money so that lawmakers “don’t have to deal with the political dynamics of having a bunch of extra cash to spend on social programs.”

As the bill neared passage this spring, the two governors sniped back and forth at each other in the media. Colorado Governor Polis called the project a “boondoggle” and said his state would “aggressively assert” its water rights. Ricketts shot back: “I didn’t know Jared Polis was so concerned about taxpayers here in Nebraska…. In fact, he’s never really talked to me.”

For now the debate is just a war of words, but it could escalate if the canal moves forward. Colorado and Nebraska have sued each other in the past over water, and indeed Colorado reached a settlement with Nebraska just a few years ago over claims that Colorado violated a water-sharing compact on a different river. Building the canal would require Nebraska to purchase or condemn farmland across state lines in Colorado, which would likely lead to litigation from private landowners as well. Colorado probably wouldn’t sue Nebraska until the latter actually began to build the canal, but if it did sue, the dispute would go straight to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The fact that such a minor water project can generate so much controversy is a sign that water security is becoming a key political issue even in places where the drought situation is not yet catastrophic. The century-old compact between Nebraska and Colorado, like the treaties that anchor the use of the Colorado River farther to the west, was designed in an era of cooperation and compromise between the states. As water supplies across the region continue to vanish, though, that interstate friendliness is vanishing with them. In its place has emerged a conflict over how to balance competing interests like agriculture and urban growth. In this case, though, the conflict is more reminiscent of a schoolyard fight than a grand political debate.