In 2019, renewable power was having a moment — but not where you’d expect. Arkansas, South Carolina, and Utah, among the reddest of red states, passed landmark legislation paving the way for expanding solar and wind power.

The bills these states enacted were all sponsored by Republicans, passed by Republican-controlled state legislatures, and approved by Republican governors. They were also bipartisan bills, getting support from Democrats, too.

Many Republican legislators still deny the scientific consensus around climate change and oppose policies to address the problem outright. But a recent study found that these red-state successes weren’t a fluke. The analysis, recently published in the journal Climatic Change, shows that states approved roughly 400 bills to reduce carbon emissions from 2015 to 2020. More than a quarter — 28 percent — passed through Republican-controlled legislatures.

“Even though some of these policies in red states might not be as ambitious as blue states, I just want people to know that things are happening,” said Renae Marshall, a co-author of the study and a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who is researching ways to reduce political polarization around environmental problems. Marshall hopes that her study could be instructive for collaboration at the federal level, where attempts at bipartisanship tend to be less successful.

In late April, Senator Joe Manchin, the Democrat from coal-friendly West Virginia who tanked his party’s climate and social policy package over concerns about government spending and inflation, started meeting with lawmakers to discuss a potential energy package that could muster up bipartisan support. At least five Republican senators have shown up so far, but securing the 10 Republican votes needed to pass a bill is a long shot. And if Democrats lose control of the House in the midterm elections, as expected, and possibly the Senate as well, any effort to pass climate legislation would require even more bipartisan cooperation.

If federal lawmakers followed the lead of their counterparts in Arkansas, South Carolina, and Utah, it could be a game-changer. So what’s causing the state-level breakthroughs on a highly polarized topic like climate change? It’s partly a matter of Republicans defining climate action on their own terms, and partly a matter of economics.

Economic opportunity

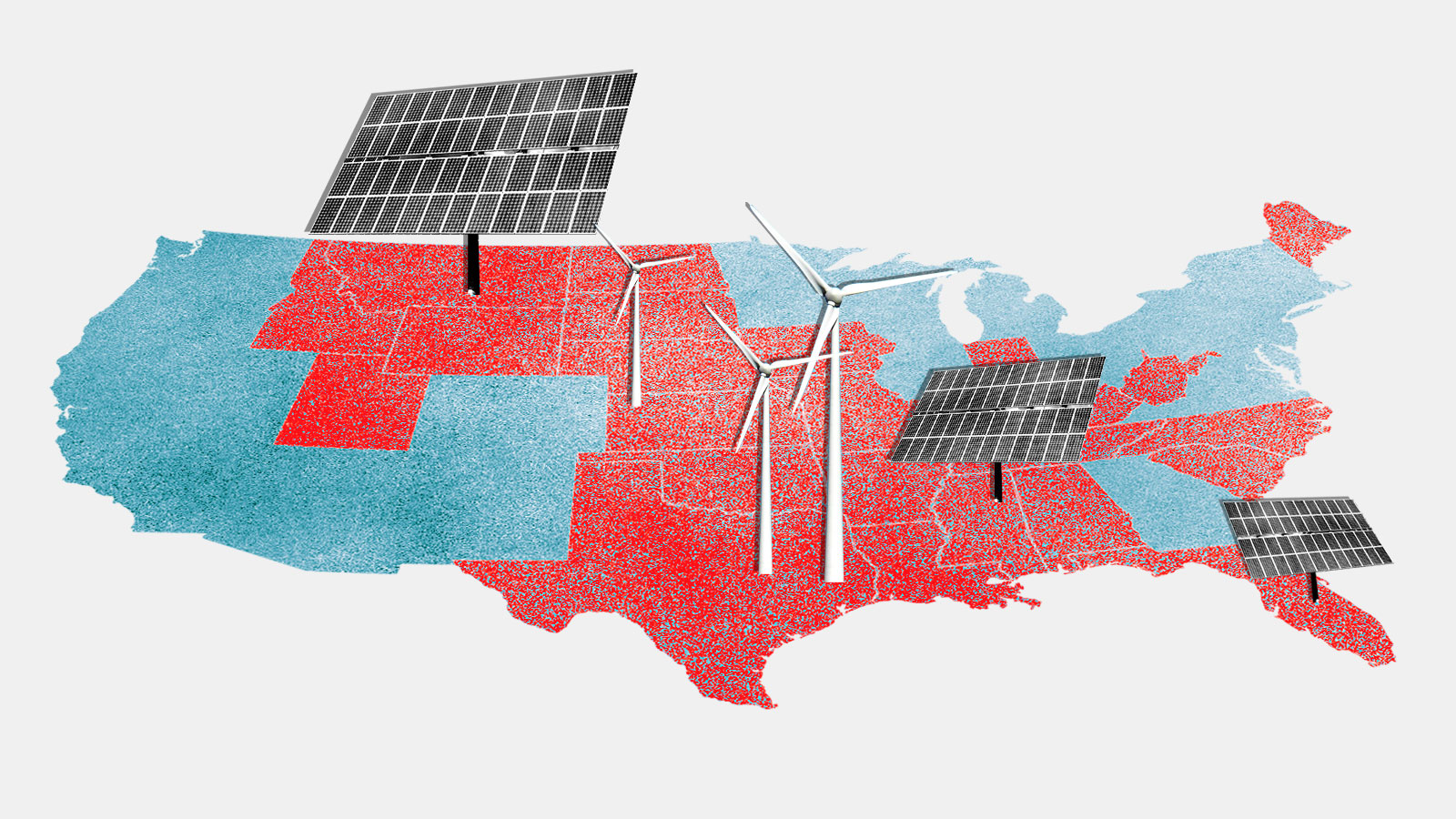

Most of America’s land is in red states — nearly two-thirds of it, going by last election’s results. And that’s space needed for things like installing wind farms and burying carbon underground. “We really cannot win on climate change without including rural America in finding solutions,” said Devashree Saha, a senior associate at the World Resources Institute in Washington, D.C.

But at the same time, Saha says, rural America has a lot to gain from renewable energy. Farmers can earn money by leasing land for wind projects, tax revenue from local solar farms can fund schools, and workers are needed to operate and maintain clean energy projects, creating new job openings.

Red states are already home to some of the largest clean energy projects. The biggest solar farm in the United States — a 13,000-acre project fittingly called “Mammoth Solar” — is being constructed in northern Indiana. Texas and Oklahoma are among the states that added the most clean power to the grid last year. Although there’s still a lot of resistance to these changes, Saha suggests that red states are doing more than you’d think to tackle the climate crisis.

“We often think of rural America as being very opposed to climate policies, but I think that’s not a very accurate portrayal of what’s happening,” Saha said.

Republican resistance to climate-friendly initiatives can start to soften if there’s a strong economic case for them. “Done right, we don’t need to lose U.S. jobs over this,” said Senator John Curtis, a Republican from Utah, during a recent panel discussion on climate change and bipartisanship. “I think we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and actually fuel our economy at the same time.”

Expanding choices

While Democrats tend to lean toward mandates and regulation — say, ending the sale of gasoline-powered cars after 2030, a goal Washington state made recently — Republicans prefer climate legislation that expands choices, rather than limiting them, according to Marshall’s study.

Take the clean energy bill that passed in Arkansas in 2019. The Solar Access Act removed the state’s ban on leasing land for solar farms, along with other solar-friendly measures, and ended up spurring new projects across the state. “It’s a great day for the Arkansas consumer,” said State Senator Dave Wallace, the Republican who introduced the bill, after its passage. “They will have more choices in the market now.”

Another example is Utah’s Community Renewable Energy Act, sponsored by Republican State Representative Stephen Handy. The act created a novel clean energy program for cities, encouraging them to adopt a goal of meeting their net electricity needs with 100 percent renewable power by 2030. Handy developed the legislation with Rocky Mountain Power, the utility serving most of the state. He says the utility’s motivation was not necessarily about climate change, but about responding to the desires of its customers, who said they wanted clean energy. “It’s all about letting the free market innovate,” Handy said.

Considering a broader set of technologies — like nuclear power and carbon capture — can also help drum up Republican support. Handy sponsored a bipartisan bill, which Governor Spencer Cox signed in March, that would allow the Utah Division of Oil, Gas, and Mining to establish regulations for capturing carbon from industrial facilities and storing it in the ground. “It never was opposed politically by either the Republicans or the Democrats,” he said.

Avoiding ‘climate change’

Some communication experts say that the term “climate change” has become so polarizing that, depending on the audience, you’re better off avoiding it altogether. Consider the name of South Carolina’s 2019 bill that made it easier for solar power to expand: the Energy Freedom Act.

“The climate debate has become part of the culture war,” said Josh Freed, who oversees the climate and energy program at the think tank Third Way. Some Republicans acknowledge the problem and are willing to discuss solutions, but rarely just to address the planetary crisis. “As soon as it’s discussed within the context of climate for climate’s sake, they sort of retreat into their corner,” he said. But that hostility can dissipate if you talk about “freedom,” national security, or economics instead.

Republicans are also more likely to support legislation that avoids other “culture wars” issues. While Democrats have recently started using language related to racism and other social injustices in their policymaking, Marshall’s study found that climate bills with bipartisan support were more likely to use language around “economic justice,” meaning that they explicitly aim to help lower-income people.

Some political scientists argue that the best climate bills are the ones that don’t get much attention. So-called “quiet” policy tackles a planet-wide problem with hundreds of small tweaks, hidden away in broader congressional bills or departmental spending. Without fanfare or attention from Fox News, these policies don’t blow up into polarizing debates. By the same token, they aren’t celebrated as political “wins” for Democrats, either. Instead, they fly under the radar, slowly shifting the country to a greener economy by giving tax credits for renewable projects or by installing charging stations for electric vehicles, for example.

Looking at the big picture of how climate policy has faltered in Congress over the last few decades, it’s easy to miss the smaller successes, even when they make it through Congress. Manchin and Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska co-sponsored the Energy Act of 2020, which included investments in renewables, energy efficiency, carbon capture, and nuclear. It passed through a Democratic House and Republican Senate and was signed by President Donald Trump in December 2020. It also phased down the production of hydrofluorocarbons, “super-pollutants” that are thousands of times more potent than carbon dioxide at heating up the atmosphere.

It was one of the most important clean energy packages the country has passed in the last 10 years, Senator Curtis of Utah said at the recent panel on bipartisan climate action.

“We don’t often tout enough our successes,” he said. “There’s so much work to be done in the climate realm, that rarely do we look back and say, ‘Oh, good job.’”