This story originally appeared in Truthout and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

In a push to capture the rural vote, 62 percent of which went to President Trump in 2016, both the Trump and Biden campaigns are ramping up efforts to appeal to farmers and ranchers.

On September 22, the Biden campaign launched a new radio ad blitz in eight battleground states, in which Biden appeals to older voters whose families have lived in rural areas for generations. “No longer are we going to be faced with children or grandchildren believing that the only way they can make it is to leave home and go somewhere else to get that good job,” Biden’s voice assures. “There’s no reason why it can’t happen here.”

In a contrasting approach, at a rally in North Carolina, just a few hours ahead of the opening of the Republican National Convention in August, Trump claimed that, under his administration, “The American farmer has done very well. I never hear any complaints from the American farmer.” Remarks later that week during the convention followed suit. “The economy is coming up very rapidly, our farmers are doing well because I got China to give them $28 billion because they were targeted by China,” Trump said on the first night of the convention.

But that assessment doesn’t square with the hardship many U.S. farmers are facing — particularly small farmers. U.S. farm bankruptcies increased 20 percent in 2019, reaching an eight-year high, on account of factors like the trade war, increasing costs of production, and crop loss related to the climate crisis.

Since April 2020, farmer support for the incumbent president has fallen from 89 percent to 71 percent, according to an August 2020 survey by DTN/The Progressive Farmer. A recent report by the Government Accountability Office revealed that under the Trump administration, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Market Facilitation Program payments to farmers harmed by the trade war went disproportionately to large-scale cotton and soybean farmers, ignoring the needs of small farmers who grow food. On account of Trump administration changes in payment maximums for the USDA’s Market Facilitation Program, the top 1.3 percent of payment recipients received an additional $519 million, while the average individual farmer in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania got $11,829 and $8,661, respectively. The finding is in line with earlier analyses revealing Trump’s disproportionate financial support for the largest capitalist farmers.

According to the USDA, more than half of the 2 million farms in the United States are “very small farms,” grossing less than $10,000 annually. When asked what political capital this group could hold, Wingate University Assistant Professor of Political Science Chelsea Kaufman told Truthout that the increased pressure small farmers face from forces like the overlapping COVID-19 pandemic and climate crisis could make them a “relatively unique” political force, as has been the case with farmers experiencing economic shocks during past election cycles.

In 1932, incumbent President Herbert Hoover lost votes from normally Republican-voting northern farmers, and the same happened for Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956. Academics attribute this to low crop prices during election years. According to the Cook Political Report, many of what are expected to be key battleground states in 2020, like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, are also top agricultural producers.

The majority of the smaller farmers Truthout spoke with for this story want to see a federal government that tackles climate change head-on and restructures agriculture to be a solution by encouraging diversified farming that stores (rather than releases) carbon. Industrial agriculture is a major contributor to climate change, through its reliance on chemical fertilizers, the manufacturing of which releases carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, and depletes the soil of nutrients. It’s a system that farmers are “stuck in,” says Tom Rosenfeld, who grows apples, blueberries, strawberries, and peaches on 120 acres of farmland in southwest Michigan. Rosenfeld purchased a conventional orchard in 2005 and has been converting it to organic ever since, which he says has been a challenge in a system that prioritizes conventional practices. Dealing with climate change has made it even more difficult, a sentiment that reflects a wider experience among farmers. In 2018, 75 percent of Farm Aid hotline calls were related to extreme weather and weather-related crises like wildfires.

Rosenfeld says more frequent late freezes due to climate change have been all but impossible to bounce back from. After temperatures dropped to 25 degrees Fahrenheit in May 2020, he lost 65 percent of his strawberries, 40 percent of his blueberries, and all of his Red Delicious, Gala, Empire, and McIntosh apples. On top of that, the changing climate has brought new pests to the region, like the apple flea weevil, which destroyed a full season’s worth of crops when it first appeared in 2010. “Every year I keep thinking, is this it?” he tells Truthout. “I can’t afford this financially; I can’t afford the time and energy and it doesn’t seem to be getting to any kind of manageable place.”

In 2018, when President Trump signed the latest Farm Bill, he reauthorized the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), which provides financial and technical assistance to farmers who implement certain conservation practices like mulching to protect soil, or “karst sinkhole treatment” to protect runoff from reaching groundwater supply.

But Rosenfeld, who is in the midst of transitioning all 110 acres from conventional to organic, says the program doesn’t offer the kind of assistance he needs. When government representatives paid his farm a visit to assess what kind of EQIP program they might support, Rosenfeld says they proposed he build a retention wall near where he fills his sprayer, to help catch runoff. “But what good does that do?” he said, referring to his ultimate goal of moving away from using any kind of hazardous material on his land. “They’re not offering the types of programs that are relevant to me as an organic grower.”

Rosenfeld says he wants to shift away from using diesel- and gas-fueled tractors and to have on-site renewable energy to power his farm. But no existing government programs make that financially feasible. When he considered investing in solar panels a few years ago, he found one program that would have cost him around $30,000, but with the kind of crop loss he has experienced, he couldn’t afford it.

Two hours north of Rosenfeld’s farm, in White Cloud, Michigan, Luke Eising is a farmer who uses silvopasture techniques, letting cows, pigs, and chickens graze together amid integrated forest and plant landscapes. Rotating the animals to different pastures encourages plants to develop more robust root systems, which returns carbon to the soil and improves soil quality. In addition to producing food for his community, Eising says, being able to help sequester carbon and rebuild degraded soil is a major reason he chose to be a farmer. According to the 2018 United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, sequestering carbon in the soil is the most cost-effective option for economic activity generating “negative emissions.” “I very much see it as a solution for food systems,” Eising told Truthout.

Eising would like to see subsidies for corn and soy cut, because he thinks regenerative practices like his would become competitive. “We’re fighting an uphill battle when I can see chicken breasts or pork chops in the store for less than I pay to process [my product],” he says, referring to animals raised in confinement and fed monoculture corn and soy feed the federal government subsidizes. Another issue the current administration hasn’t helped with, Eising says, is a major meat processing backlog. Whereas Eising can usually get a date within six to eight weeks at a meat processing plant, given meat plant shutdowns amid COVID-19, leading to short supply of meat processing facilities, it’s been hard to find a date any time before 2022. “This is not okay. I have animals outside that are ready to process, I have customers lining up because they’re hungry and I have a freezer that’s empty,” he says. Existing laws prohibit small, local butchers from processing meat headed for market.

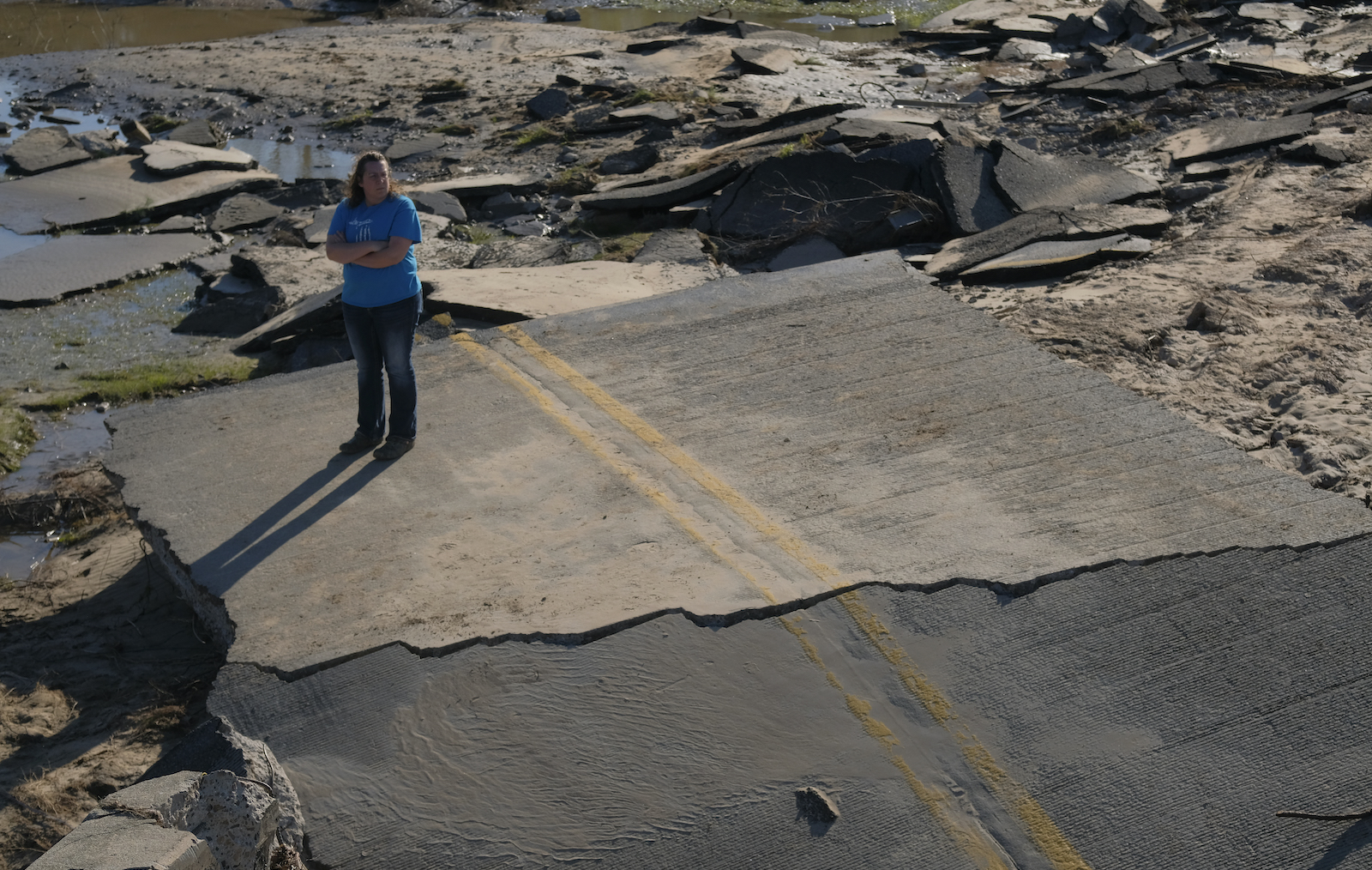

Eising tends to vote for conservative or libertarian candidates in local and national elections. In 2016, he voted for libertarian candidate Gary Johnson. But Eising says he’ll likely vote for Biden if polling remains close in Michigan. “Nobody else is at all interested in what regenerative farming could do for this country,” he says. Biden has recently talked about paying farmers for “planting certain crops that in fact absorb carbon from the air,” but his climate plan makes no mention of organic, diversified, or regenerative farming. According to a report by Data For Progress, conventional farming practices that rely on pesticides and monoculture practices are linked to $44 billion in annual damage related to soil erosion in the United States, which is perhaps felt most acutely in areas where soil can no longer retain moisture in the advent of a heavy rain, leading to catastrophic flooding.

Ecologically minded farmers in swing states outside of Michigan similarly reflect a desire for leadership that addresses climate through agricultural reform. Kemper Burt began farming 40 years ago in California. He now lives in Arizona, where he grows lettuce and other produce on a 40-acre farm powered by solar energy. Burt points out that tackling climate change will entail decolonizing the way we produce food, in direct contrast with the “feed the world” mentality behind the so-called “Green Revolution” of the 1970s, which led to the fertilizer- and pesticide-heavy monoculture farming he and other small-scale farmers want to break away from. “Let’s just try feeding our community, then let’s just try feeding our state, and then let’s just try feeding other states,” Burt says. Burt is registered as an independent, though he wouldn’t say exactly how he’ll vote in November. “I look to what people are doing to help protect nature, which then in turn protects you and I,” he said.

Many small farmers say they’ve yet to see a presidential candidate or down-ballot candidate fully address their needs in this election cycle. President Trump’s reelection campaign has not yet put out a climate plan. And Biden’s climate plan does not yet spell out what small-scale farmers say they want, like a return to the New Deal-era concept of “parity,” a supply-management strategy designed to prevent the kind of wasteful overproduction of soybeans and corn that wipes the land of biodiversity and results in unstable prices. Rosenfeld wants to see a shift away from crop insurance, which comprised one-third of farmers’ income in 2019, toward income insurance, which would provide financial support for people growing food, rather than cash crops.

As long as agriculture is considered a solution to the climate crisis, whether in a Green New Deal or as part of another climate plan, says Maine farmer Craig Hickman, he’d consider it a step forward, noting that he thinks his neighbors in Maine, many of whom are libertarians, would agree. “Investing in food infrastructure is as important as roads and bridges,” he told Truthout.

In 2019, Maine, a “purple” state, passed the first state-level Green New Deal backed by labor unions. Facing increased pressure from forces like climate change, the potential “farm vote” could build swing power, “although it is not clear whether that would happen in 2020 or a later election year,” Kaufman said. “We can look to the lessons of history: Farmers had quite unique behavior at points in time where they faced economic instability, which led them to support candidates and parties that addressed these issues.”