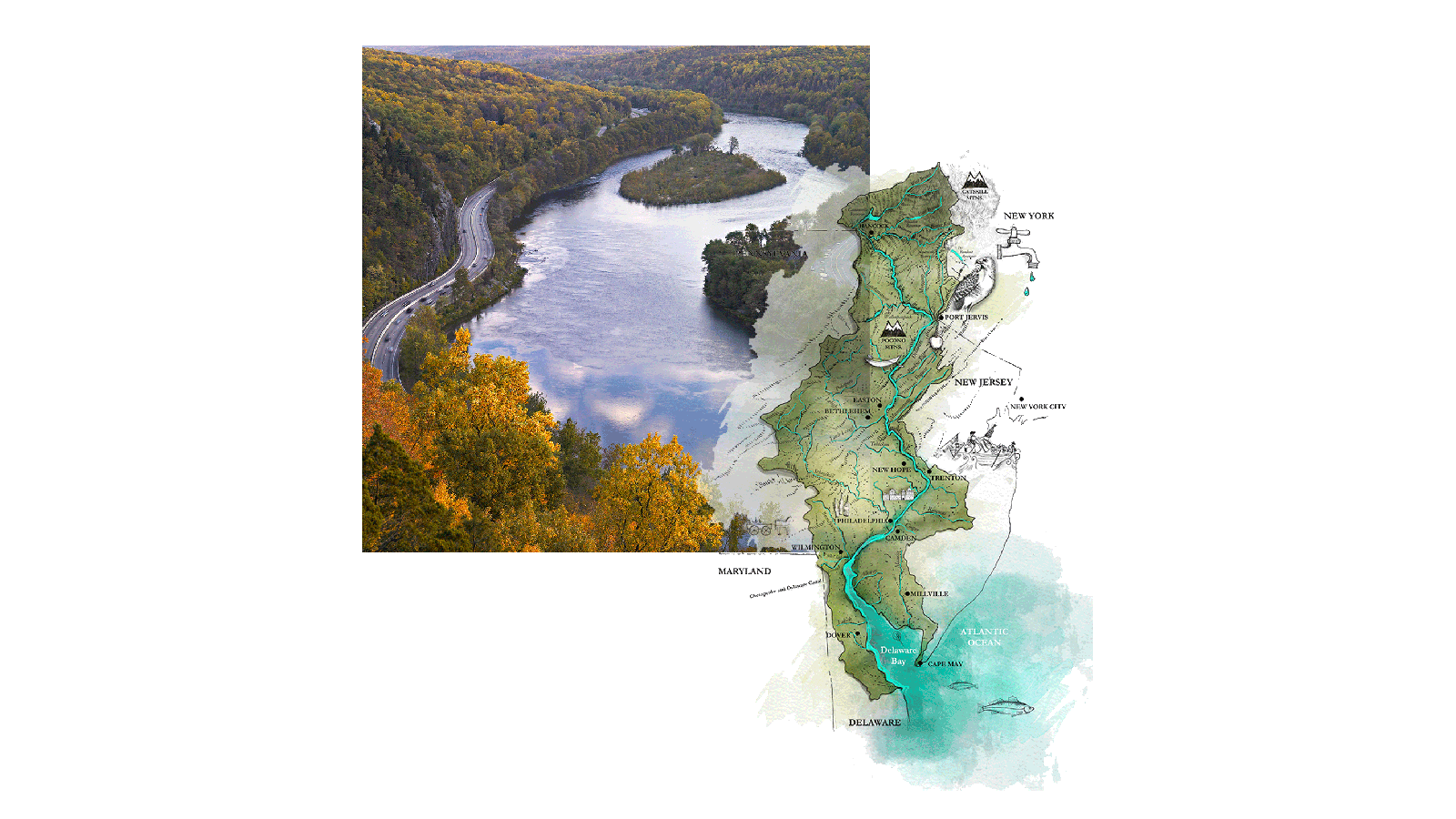

In late February, the Delaware River Basin Commission made a historic announcement: It banned hydraulic fracturing in the basin, a 13,539-square-mile area that supplies some 17 million people with drinking water.

“Prohibiting high volume hydraulic fracturing in the Basin is vital to preserving our region’s recreational and natural resources and ecology,” said New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, who represents one of the four states in the Delaware River Basin Commission, or DRBC. “Our actions,” he added, “will protect public health and preserve our water resources for future generations.”

The decision to permanently protect the watershed from fracking was the culmination of years of dedicated activism and public input. Politicians, environmental groups, and citizens alike celebrated the decision by the commission — a powerful, interstate-federal regulatory agency made up of the governors of Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania and the commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ North Atlantic Division.

But the same commission that made the historic decision to protect the basin from fracking also voted several months earlier to pave the way for a natural gas company to use the Delaware River to export its product abroad.

In December 2020, the DRBC voted to approve construction of a dock in the New Jersey city of Gibbstown, in Gloucester County. That dock, attached to an export terminal constructed on the site of a former Dupont munitions plant, will receive a fossil fuel called liquefied natural gas, or LNG, from a plant in northern Pennsylvania and then ship it overseas.

When complete, the Delaware River Basin’s first-ever liquefied natural gas project will pose immediate risks to a wide swath of the Eastern seaboard — to people who live near the liquefaction plant in Pennsylvania and to communities clustered along the 200-mile route between the plant and the export dock in New Jersey — as well as to the Delaware River itself.

The two decisions weighed against each other point to an interesting paradox in the DRBC’s attitude toward natural gas, a significant contributor to global warming. While the commission doesn’t want exploration to pollute the basin, it’s still tacitly permitting the industry to use the river for a different side of the natural gas business — one that’s not without its own environmental and health threats. The rulings illuminate the complex, often contradictory relationship with natural gas that many policymakers find themselves in at the moment, as pressure builds for communities to transition away from fossil fuels toward a clean economy.

Bait and switch?

In 2016, New Fortress Energy, a natural gas company, put in an application to build a dock in Gibbstown, New Jersey, via an infrastructure-focused subsidiary called Delaware River Partners. Environmentalists and some nearby residents opposed the dock at the time — it would be constructed on a 300-acre parcel of land and superfund site that used to be a Dupont munitions factory. Cleanup of contaminants left by Dupont was ongoing in 2016, and decontamination of the groundwater there still hasn’t been completed.

In order to reassure regulators and nearby communities, the managing director of New Fortress said it wouldn’t use the dock to export LNG. The subsidiary would instead stick to exporting fruits, vegetables, automobiles, and small quantities of propane and butane. The Gibbstown Logistics Center port was approved by the Delaware River Basin Commission in 2017 and constructed not long after that. The situation wasn’t ideal for environmentalists, but it was tolerable. It didn’t stay that way for long.

In 2019, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, one of the environmental groups that had opposed the initial project, caught wind that New Fortress Energy, via a different subsidiary called Bradford County Real Estate Partners, had applied for a permit to build an $800 million natural gas liquefaction plant in Bradford County, Pennsylvania — within the heart of the Marcellus shale formation — to be completed in the first quarter of this year. (That timeline was ultimately delayed by COVID-19.) When it’s up and running, the liquefier will produce 3.6 million gallons of LNG per day. In a Securities and Exchange Commission filing, New Fortress Energy said the gas would be exported from “a port on the Delaware river.”

“Everything clicked,” Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, said. A few months later, she saw an announcement for a DRBC hearing and immediately guessed what it would be about. Sure enough, Delaware River Partners, the New Fortress subsidiary that constructed the dock in New Jersey, was applying for a permit to build another dock, with two berths this time, attached to the Gibbstown Logistics Center. Carluccio knew what only a few other community stakeholders knew at the time: If approved, the new dock, called Dock 2, would be used to export fracked gas from Pennsylvania.

Danger, extremely flammable

LNG is natural gas that has been cooled to negative 260 degrees Fahrenheit — a temperature almost as cold as the planet Saturn — in order to transform it into a liquid. It expands to more than 600 times its compressed size if it is accidentally released from a storage tank and sometimes forms LNG clouds as it warms and expands. Those clouds can travel miles when the wind is blowing and will detonate if triggered by a spark. There’s no way to put out an LNG fire — it has to burn itself out. The thermal radiation from such an event can cause second-degree burns in as little as 30 seconds.

Because of these risks, there has long been a federal ban on transporting LNG via rail in dense areas in the U.S. But New Fortress got a special permit in 2019 from the Trump administration to use rail to transport the gas from Pennsylvania to New Jersey. And in 2020, then-President Donald Trump fully lifted the ban via executive order. His Department of Transportation released an analysis that said transporting LNG by rail or truck is relatively safe. An analysis from the environmental nonprofit Earthjustice estimated that the liquefied gas from a single rail tank car, if detonated, could raze an entire city.

New Fortress Energy plans to transport the liquefied natural gas in either tanker trucks or by rail some 200 miles from Bradford County to Gibbstown, snaking through dozens of communities along the way. More than a million and a half people live within a 2-mile radius of the possible LNG transportation routes. Twenty-nine percent of those individuals, a little less than half a million people, are people of color, and 24 percent, some 400,000 people, are low income. In a letter to the DRBC last December, Philadelphia city officials wrote that New Fortress Energy’s LNG transport route through Philadelphia “will expose black and brown and low-income communities to the most intense and inescapable zone of impact should there be an accident such as a derailment.”

The dangers of producing liquefied natural gas are also acute for the communities located near the LNG plant and export terminal. Roughly 600 people live in Wyalusing Township, the community in Bradford County where the plant will be built. Thousands more live within a few miles of the export terminal in New Jersey. Paulsboro Township, which qualifies as one of New Jersey’s “overburdened communities” because at least 35 percent of the households there are low income and minority, is three and a half miles away from the Gibbstown Logistics Center.

There have been 13 serious accidents at LNG plants, LNG terminals, and other onshore LNG facilities worldwide since 1994. The worst of those, a fire at a terminal in Algeria in 2004, killed 27 workers and 74 others. LNG liquefaction facilities can also produce air pollutants like carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide, as well as hazardous waste.

Then there’s the matter of the superfund site where Dock 2 will be built. According to a 2019 lawsuit from New Jersey attorney general, the Gibbstown site contains “a diverse and significant amount of hazardous waste” dumped into “unlined landfills, sand tar pits, pipes, and ditch basins.” The deep-water dredging required to construct the new LNG export dock — more than 134 million gallons of sediment over 45 acres of water — could launch lingering polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, into the river. PCBs have been linked to increased rates of many types of cancer in humans, including brain cancer, liver cancer, and gastrointestinal tract cancer.

Producing and exporting LNG affects the climate, too. In a 2019 Air Quality Plan Approval document, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection estimated the plant will produce more than a million metric tons of greenhouse gases in a 12-month period. Environmental groups say the true climate impacts of the plant are likely higher because “fugitive emissions,” leaks and other irregular releases of gases, are not typically taken into account by such assessments. When the LNG is actually burned by whichever countries end up buying it from New Fortress Energy, it will produce many millions more metric tons of emissions.

The green light

After hearing about the planned DRBC meeting to consider the construction of Dock 2 at the Gibbstown logistics center, environmental groups sounded the alarm, sending letters to state agencies and educating communities along the proposed route about the dangers of the project.

“New Jersey would get all the risk, there’s no reward for this type of project,” said Ed Potosnak, executive director of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters. “The surrounding community is already an environmental justice community.”

Yet despite opposition from environmentalists and community groups, the project has benefited from strong support from several business associations, policymakers, and unions — including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the Iron Workers Union, and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters — thanks to the promise of the jobs it would create.

At a hearing in June 2019, the commission unanimously approved Dock 2. In response to concerns about the environmental and climate impacts of the project, the commission said that such issues should be resolved “incrementally” at the state, interstate, and national levels. “Our evaluation,” it wrote in a memorandum, is “focused on management of the Basin’s water resources and not on wider energy policy questions.” The Delaware River Basin Commission declined to comment for this story, citing ongoing litigation around the port. New Fortress Energy did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesperson for Governor Murphy’s office told Grist that New Jersey voted in favor of the new dock because the DRBC was considering only the narrow question of whether Delaware River Partners could construct the dock, not whether New Fortress Energy could export LNG from New Jersey. Carluccio doesn’t buy it. “You would have to struggle to put on blinders and noise-canceling earphones to avoid hearing the wide-ranging issues that LNG presents at the facility,” she said.

Delaware Riverkeeper Network appealed the decision, but a federal judge affirmed the approval of the dock over the network’s objections and sent it back to the DRBC one last time for a final vote on the project. At that hearing, in December 2020, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the Army Corps of Engineers voted to approve the dock. New York moved to delay the vote, but the motion failed, and the state proxy ultimately abstained from voting.

An ongoing battle

The LNG export project is not a done deal yet. New Fortress Energy still needs to obtain environmental permits from New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection and an export permit from the Department of Energy. And it can’t start construction until September 15 at the earliest — the Army Corps of Engineers’ permit for the dock has a condition that does not allow for any construction work in the water during the Atlantic sturgeon spawning season, which runs for six months starting on March 15. Meanwhile, the Delaware Riverkeeper Network has sent a motion for summary judgment — which asks a court to decide a case without a trial — to the New Jersey district court requesting that the Army Corps of Engineers’ permit for Dock 2 be thrown out because the Corps failed to do a full environmental impact assessment of the dock before it approved the project, in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act.

Environmental and community groups are hopeful that the Biden administration will step in to stop the project, which was largely approved during Trump’s term. The Army Corps, for example, could choose not to defend itself in court if the Biden administration decides that it agrees with the Delaware Riverkeeper Network’s lawsuit. Or the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, which oversees many aspects of the U.S. energy landscape, could rule that it has jurisdiction over the construction of New Fortress Energy’s facilities. The commission’s new chairman, Biden-appointed Richard Glick, recently announced that the commission will be taking environmental justice into account when approving projects. That could affect Dock 2 and New Fortress Energy’s hopes of exporting LNG from New Jersey. “Possibly, for the first time, environmental justice considerations are going to be heard on a consistent basis at the commission,” Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at nonprofit consumer rights advocacy group Public Citizen, who has been keeping tabs on New Fortress Energy’s dealings with FERC, told Grist. “That’s really, really important.”

President Joe Biden could also revoke Trump’s executive order allowing LNG to be transported by rail. At his confirmation hearing in January, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg was pressed by Senator Ted Cruz from Texas on his views on Trump’s LNG-by-rail rule. “The best, honest answer I can give you now is that I’ll be taking a hard look at it,” Buttigieg said.

Dock 2 is a test case for how far the Biden administration will go to prune the Trump era’s pro-industry legacy. The LNG-by-rail rule, FERC’s new environmental justice considerations, and the Army Corps of Engineers’ role in the DRBC will come into play in the coming months. Whether or not the project eventually hits a dead end, the years-long controversy over the export of natural gas in Gibbstown demonstrates that “banned” doesn’t always mean “eliminated.”