Our partners at Climate Desk have an overview of a series of recent polls that lead to one conclusion: People are increasingly concerned about climate change. And “people” obviously means “undecided voters” — since those are the people who count for the next 34 days.

[protected-iframe id=”dd29f8cf3bb5f97746bbce656e6219f0-5104299-36375464″ info=”http://www.nbc.com/assets/video/widget/widget.html?vid=1418227″ width=”470″ height=”264″ frameborder=”0″]

The findings, in summary:

[I]t is not that any type of climate communication is a guaranteed win—just that it is far from a guaranteed loser. But that still leaves a growing disconnect between politicians’ fear of the climate issue on the one hand, and emerging public opinion data on the other. “Democrats don’t need to be as afraid of this issue as they are,” says [Harstad Strategic Research pollster Andrew] Maxfield. From President Obama on down, if candidates who talk about climate change win in 2012, expect that situation to rapidly change.

For all of the optimism that climate and the environment will become a point of political leverage for candidates, it won’t. And the reason is apparent if you dive a little deeper into the numbers.

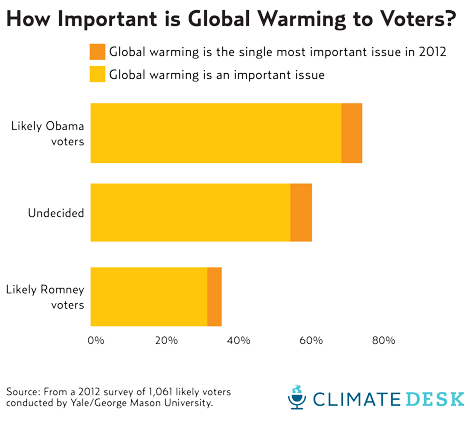

The key is this chart.

This is the closest we get among the data cited to the core question: How much do people prioritize the climate? And the answer, after a quick read, is “not very much.”

Ignore the pale yellow bar. Being “an important issue” to a voter is like being “an issue that I have heard of.” Is preserving the safety net important to you? Getting troops out of Afghanistan? Food safety? Lots of things are important to lots of people. What matters is that dark orange, those people who say that climate change is the top issue for them, the most important thing — because those are the people who will insist that politicians hear them. Even among Obama supporters, that figure is less than 10 percent.

There are two things that influence political decision-making: relationships and cover.

By relationships, I mean literal, in-person relationships. The reason people contribute thousands of dollars to political campaigns isn’t because it’s a form of bribery; people give money so that a candidate knows them. So that when they call or stop by, the candidate will sit down and listen. So that, someday, the candidate and the donor can be friends. That’s a relationship that gives a lobbyist a lot of time to make his case.

By cover, I mean that this is a democracy. Politicians are hesitant to take action on an issue unless they feel as though there is a visible base of support. The key there is “visible.” Politicians don’t want it to appear that they’re rejecting popular opinion, nor are they excited about facing loud opposition without any backup. Politicians are risk-averse. If everyone believes that something is popular, they’ll do it — even if it isn’t actually popular. This is part of the explanation for the Tea Party. The group got an outsized amount of attention (thanks, Fox!) meaning that politicians faced a steep road if they chose to oppose Tea Party policies.

There’s a corollary to cover: fear. Politicians face the threat of losing their jobs every two, four, or six years. During a campaign, they want to do everything they can to limit damage. So they’re loathe to take an action that will result in a million dollars worth of TV ads attacking them.

In the current political debate, D.C. politicians are given an enormous amount of political cover by the fossil fuels industry. The industry runs ads, it creates advocacy organizations, it lobbies heavily. It leverages the relationships it buys with its massive political contributions to present the case that fossil fuels are popular and necessary. It threatens to — and does — launch massive ad blitzes against unfriendly politicians.

The fossil fuel industry is demolishing environmental advocates, and it’s likely to continue doing so for some time. The big environmental organizations are resource-constrained nonprofits. They don’t have the kind of money it takes to build relationships on Capitol Hill and they’re ineffective when engaging in political campaigns. Relationships with politicians exist, mind you, but they’re with sympathetic elected officials — not nearly enough to carry a majority in the House or Senate. Especially when politicians can see ExxonMobil pulling out a checkbook.

Which at long last brings us back to voters. Sometimes, voters change the dynamic. They build so much pressure, establish so much political cover, that they can’t be ignored. Think gay marriage, Vietnam. Victories that were slow in coming but were catalyzed by grassroots energy and passion.

That orange and yellow graph makes one thing clear: Among voters, that energy and passion is missing. It shows awareness and dispassion, meaning that elected officials can safely ignore the issue. People know it exists, but they don’t care. They’re not going to fund a campaign; they’re not going to march on Capitol Hill. No relationship, no cover, no fear. So no political clout.

And now, a ray of sunshine from that Climate Desk post. Sort of.

[E]xtreme weather is leaving Americans increasingly worried about climate change. A mid July survey from the University of Texas-Austin, for instance, found that 70 percent of the public thought climate change was happening, an increase from 65 percent in March.

People are coming around to climate change as a function of lost homes and lost lives. As the impacts of climate change become more pronounced, passion will be engendered. Political cover will exist.

And, with a lot of luck, it won’t be too late.