It’s important, this time, to draw conclusions, and to do so publicly. Because Bali has taken us — barely and painfully — over a line and into a new and even more difficult level in the climate game we’ll be playing for the rest of our lives. In fact, it’s not too much to say that, with the realizations of the last year and their culmination at the 13th Conference of Parties, the game has, finally, belatedly, begun in earnest.

First up, we knew going into Bali that if the old routine continued without variation, we’d really be in trouble. The timing of this meeting alone made this clear. Here we were, after the skeptics, after the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report, after Gore’s (and the IPCC’s) Nobel Prize. We know now how grave the situation is. So it’s with great relief that I’m able to say that, judging at least by Bali, the game has indeed changed — except, of course, for the United States.

The most important change was that the G77, the South’s negotiating bloc, did not put its unity above all else. This unity was always easy to understand, for the South is weak and the G77’s members know all too well that when they don’t hang together they hang separately. But it’s been clear for years now that the G77’s unity can itself be a terrible problem, one that allowed its most retrograde members (the Saudis come to mind) to override the interests of weaker parties (like, for example, the Alliance of Small Island States). So Bali, the COP where China, South Africa, and Brazil stepped forward to announce their willingness to take on binding “commitments or actions,” was a real breakthrough, not least because the attached condition — “measurable, reportable and verifiable” assistance from the industrialized to the developing countries — was so widely understood as being both just and inevitable.

Not that we didn’t already know that, without southern support for rapid action, there won’t be any. But the G77’s “flexibility” gave us a different kind of knowledge, concrete knowledge of a deal made and a way forward. While it didn’t change everything, it changed a great deal.

Second, there’s the matter of money. Money for adaptation. Money for technology transfer. Money for capacity building, and money, most of all, for development, which must go on, albeit in new ways, even in this climate constrained and otherwise strained world. We knew about the money, too, of course. How could we not? But not like we know it today, when the need for rapid global emissions cuts of at least 50 percent has, as Bali made absolutely clear, become the consensus position.

Case in point: Nicolas Stern, who only a few days before the Bush delegation’s humiliation at Saturday morning’s overtime plenary (see here for a vivid account), heartened the attendees of a small, poorly attended side event by telling them that the rich countries would have to not only make sharp domestic reductions, but would also have to finance parallel reductions in the developing world. This because, as he put it in a published commentary called “now the rich must pay,” “even a minimal view of equity demands that the rich countries’ reductions should be at least 80% — either made directly or purchased.” Moreover, and significantly, Stern went out of his way to note that the needed financing would not result from a regime in which equal per-capita emissions rights were taken as proxies for the necessary rich-world financial commitments. “Contraction and Convergence,” he said, is “a very weak equity principle,” and something stronger would be needed.

Third, Bali saw the long-overdue encounter between the climate movement and the global justice movement finally pass beyond its scattered preliminaries. These are still early days, of course — for a quick review of how things played out in Bali see this article by Walden Bello — but it’s already clear that neither movement will ever be the same. Even mainline climate folks talk often about equity now, and this is new. Moreover, they do so even though they fear its implications, which, frankly, they’re right to do: Taken seriously, climate equity has the potential to raise the stakes visibly and dangerously high, so high that both our politicians and our populations would tend to balk. That’s all the more reason to admire the ground crossed, because fewer and fewer people within the climate movement can imagine a future without justice, and for the most part they do not wish to try.

Nor will the greens be the only ones transformed by this encounter. Global justice activists will also have to shed old skins for larger, more capacious frameworks and approaches. There’s much to say here, but the key is that a “radical” movement — which has, to this point, made its mark by exposing the charade of the Clean Development Mechanism and then going on to oppose all market mechanisms — is now visibly confronting a larger challenge in which mere opposition is not enough. If it would speak effectively for the poor and the vulnerable, then it must find a larger frame. The question now is motion, very rapid motion, and if false solutions are a terrible danger, so too is the illusion that by exposing that danger we have done all we must, all that we are called upon to do.

This too was clear at Bali. Or so at least it seems so in the final statement of the grassroots groups that joined together in a “Solidarity Village” near the Bali conference center. That statement says that, “By climate justice, we understand that countries and sectors that have contributed the most to the climate crisis — the rich countries and transnational corporations of the North — must pay the cost of ensuring that all peoples and future generations can live in a healthy and just world, respecting the ecological limits of the planet.”

In any case, global emissions must peak, and very soon. In the face of the astonishing arrogance and duplicity of the Bush administration, the final Bali Action Plan (PDF) did not make this explicitly clear, but there are at least clear references to the Fourth Assessment Report, and they will do. Everyone knows what they mean. If we’re to bend the emissions curves as we will need to, we’ll have to start soon, and we’ll have to create new understandings and institutions as we go. It’s not enough to oppose false solutions. We need real ones.

So Bali was perhaps as great a success as could be expected under the shadow of today’s Washington. The negotiations are go, and we shall fight another day. And we’ll do so within a framework that — by the insistence of the G77! — calls for measurable, verifiable, and monitorable progress on finance and technology. To be sure, this is not a concrete success. Bali did not lay out national obligations, or even a global target, and its outcome is easy to criticize. I could do it myself, no problem. But the truth is that Bali was never going to lay out the details, or even a comprehensive framework. And it did manage to lay down the challenges, to be faced again in the real battle, the one that will be fought in two years time. Bali is all that was possible, and it’s enough.

Moreover, we are wiser now — and, hopefully, more ready for the coming rounds. They will be vicious indeed. And I must add that, from here on out, they will not be won with frameworks and good intentions. We now need to step beyond the conditions of possibility of a fair and viable global accord, and spell out the thing itself.

When we get down to cases, we’ll have no choice but to face the details of an extremely daunting reality. Fortunately, Bali brought good news on this front as well. Not just the fact that, a few skeptical dead-enders notwithstanding, the threat was taken all around as justifying emergency action. But also that, at least as far as I could tell, people were ready, if not actually eager, to connect the dots.

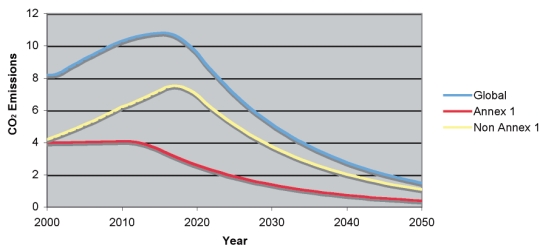

That, at least, is the conclusion I draw from the warm reception afforded to one of our own graphs, one embedded in a slide deck we prepared for our Greenhouse Development Rights project and presented in a number of side events — one that almost seemed to “go viral” to the point that, by the end of the COP, we were encountering it in other peoples’ presentations. We would find ourselves listening as others they displayed, and spoke to, our “subtraction slide.” Which looks like this:

The story here is the story of the future, and it’s as simple as it is significant. Think of it as one that involves a little bit of science, little bit of conjecture, and a little bit of arithmetic.

The blue line is the science, which is to say it shows what the science is telling us our global emissions trajectory must be if we want to preserve a reasonable likelihood of keeping the warming below 2°C. It’s a global emergency pathway, and there is no denying that it is extremely ambitious — it sees emissions peaking by 2020 and declining 80 percent by mid-century. Yet even this — a pathway that would require an unprecedented global mobilization — implies considerable climate risks. It would leave us with a probability of exceeding 2°C of roughly 20-35 percent, which is vastly better than doing nothing but somehow not tremendously comforting.

The red line is the conjecture, which is to say that it isn’t entirely far-fetched to suppose that the developed countries will accept their obligation to make very, very ambitious cuts in the North. Suppose that they all managed to reduce their emissions as quickly and deeply as Al Gore, for example, has called for in the U.S. The red line shows this 90 percent reduction in emissions (below 1990) by 2050, across all of the Annex 1 countries. Thus, it shows us the portion of the available global carbon budget that the North would consume if it were to follow a very ambitious course of emissions reductions.

Now, if the North managed this, what would it imply in the South? Here’s where we come to arithmetic. The yellow line shows how much of the limited remaining global carbon budget would be left to be consumed by the South. And it’s not much. In fact, the South, even though on average its people are still quite poor, would need to somehow develop along a path that peaks and declines very, very soon indeed: by 2020. And this is precisely the challenge of climate stabilization in this divided world. This is where the tension between climate protection and development comes in. This is where the global climate policy impasse resides.

The truth here is more than inconvenient. It’s shocking, even terrifying. Because what it tells us is that we’re going to have to get this right, and soon. And that the battle of 2009 will be a doozy. And that there will be no way to win it without both trust and technology, and both of them on a grand scale. And that before we get either we’ll need breakthroughs in financing and, of course, burden sharing. And that we’ll also need to step outside the climate negotiations to fight for “policy coherence,” in which the institutions of trade and investment are brought quickly into line with the imperatives of the climate regime.

And that we’ll need justice. For without it there will not be cooperation, or solidarity. And without global solidarity, we will fail.