H

ey there, welcome to another issue of Record High. My name is Zoya Teirstein, and this week I’m taking you inside emergency rooms in Phoenix — a place that just endured 31 consecutive days at 110 degrees Fahrenheit or above. It was the hottest month, on average, in any U.S. city on record.

To understand how those temperatures are affecting residents in real time, I spoke to two physicians in Phoenix about what this summer of extremes looks like in their domain, the emergency room. As I reported this week, Kara Geren and Frank Lovecchio, two emergency medicine physicians in the metro of 1.6 million people, have been seeing patients show up with the same exact symptom: dehydration. No matter what the patient comes in for — whether it’s chest pain or a chronic health condition such as diabetes — they also likely need fluids. “What surprised us is even people that came in for completely unrelated things are dehydrated,” Geren said. “It’s just so hard to stay hydrated.”

The patients presenting with surprise dehydration add to the considerable number of people coming to the ER with symptoms consistent with heat-associated illness: heat rashes, cramps, vomiting, diarrhea — and the most severe form of heat sickness, heat stroke. But Geren and Lovecchio have also seen a number of patients with severe burns from hot pavement and scorching surfaces. On a 100-degree Fahrenheit day, asphalt in direct sunlight will heat up to 160 degrees — more than hot enough to give someone a third-degree burn. “Our burn unit is very, very busy,” Lovecchio said.

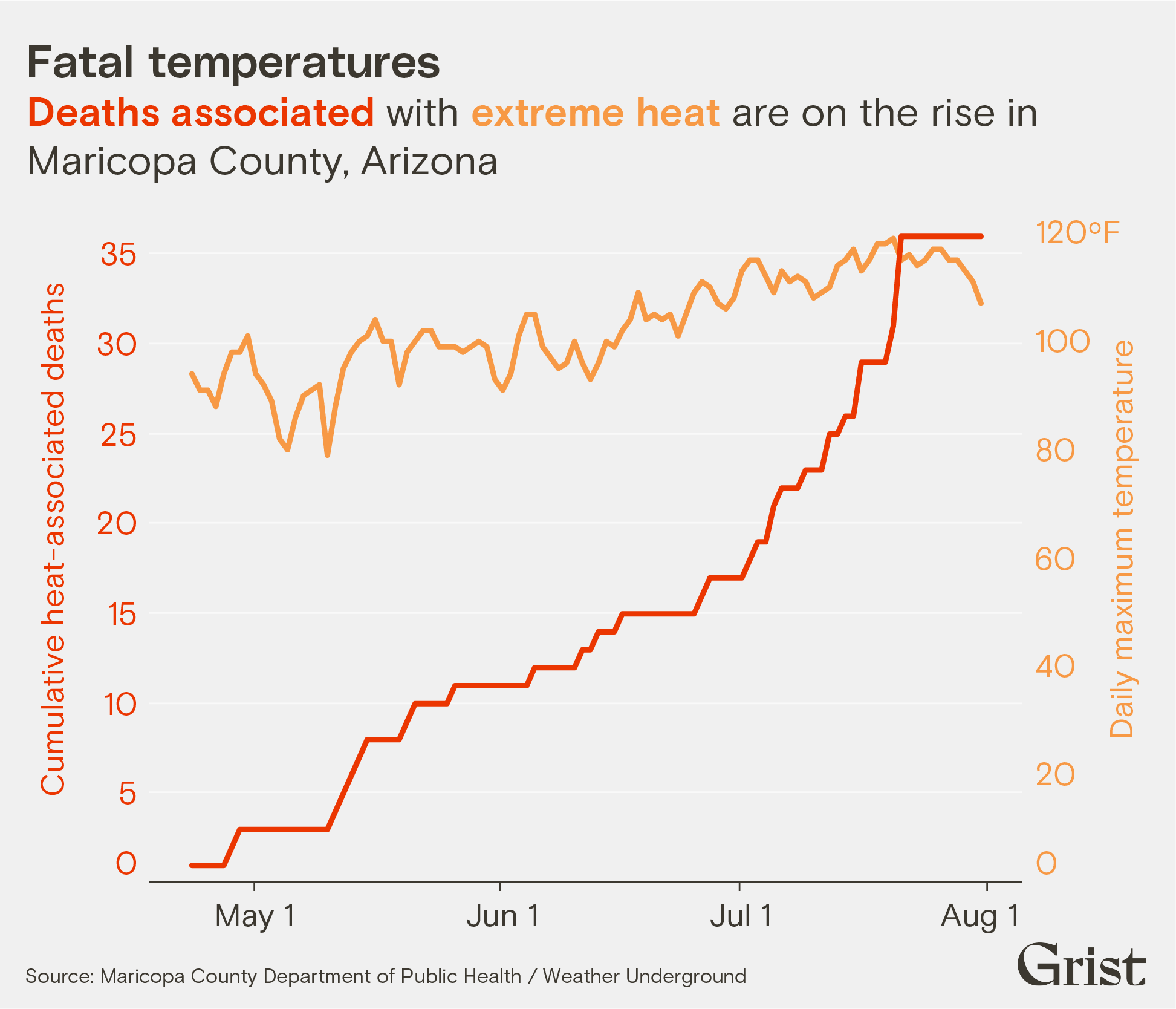

The Maricopa County Department of Public Health, covering metro-area Phoenix, has reported 39 deaths connected to heat since April; the medical examiner’s office suspects there have been 312 more deaths associated with heat in the county, which are currently under investigation. The elderly, the unhoused, and people who use opioids are especially at risk of developing severe heat sickness and dying.

Geren and Lovecchio have been cooling people down however they can — they immerse patients in large tubs of cold water or zip them into body bags filled with ice. They chill intravenous fluids and oxygen before administering them, and cool patients with industrial-strength fans. But both doctors worry about the future.

“A lot of people have that billion-dollar question: Is [Phoenix] going to become unlivable? I think it’s pretty close this summer.”

Frank Lovecchio, ER doctor in Phoenix

There are efforts underway at the federal level to fund solutions. Last week, Democratic lawmakers, including Arizona’s Ruben Gallego, reintroduced the Preventing HEAT Illness and Deaths Act, legislation aimed at mitigating deaths by reducing people’s exposure to extreme heat. That’s in addition to Gallego’s efforts to get FEMA to add extreme heat to its qualifying list of major disasters, as my colleague Jake Bittle reported in this newsletter last week.

But it’s unclear how far those bills will get. Many Republican lawmakers, improbable as it sounds, are moving in the opposite direction. In mid-July, House Republicans proposed deep cuts to the budgets of both the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Interior. The effort is unlikely to be successful, with Senate Democrats sure to block it. But the GOP’s spending bill, which proposes slashing EPA funding by nearly 40 percent, shows how the right is thinking about this summer of extremes.

Policy experts at the Environmental Defense Fund told Grist that one of the programs that could face the chopping block if Republicans get their way is the EPA’s Heat Island Reduction Program. The initiative seeks to decrease exposure to extreme heat in urban areas with little tree cover, particularly in low-income and minority communities that are disproportionately burdened by extreme heat.

Meanwhile, Geren is thinking ahead to next summer and even hotter summers to come. “If we’re keeping the way we are, I just don’t know how people can live here,” she said.

By the numbers

In Arizona, one of the states where heat-related deaths are most common, the number of fatalities in metro-area Phoenix have been rising in recent years. This year, officials have reported 39 deaths connected to heat so far, but that number will likely change as the summer continues and hundreds of other deaths are investigated.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern / Grist

What we’re reading

The wacky world of heat insurance: You’ve heard of flood insurance and wildfire insurance, but what about heat insurance? A new suite of unconventional heat insurance products has emerged in a range of countries around the world. Can they help protect us? My colleague Jake Bittle reports.

How heat isolates: Americans are becoming increasingly isolated. Believe it or not, that can make extreme heat more fatal. My colleague Akielly Hu explains how isolation compounds the risks of heat exposure and how cities can reduce those risks.

Children threatened by extreme heat: A United Nations report shows 460 million children under the age of 18 in South Asia are already exposed to 83 or more days a year in which temperatures exceed 95 degrees. Three-quarters of children in the region are exposed, compared to one in three children globally.

South America is rewriting the climatic books: It’s supposed to be the middle of winter in Chile and Argentina, but temperatures in the region are abnormally high — upward of 100 degrees Fahrenheit in some areas. “Some places have even reached all-time maximums — surpassing summer temperatures, even though it is winter,” Ian Livingston wrote for the Washington Post.

Extreme heat is ‘boring’: Scoff at the headline, but give this essay on cabin fever, or “climate ennui,” in Arizona a chance. Caroline Tracey writes a blazingly good first-person account of being trapped indoors during the summer in Tucson for Zocalo Public Square.

Heat comes with a steep price tag: New research shows extreme heat is costing the U.S. economy big time — $100 billion in 2020 and a projected $500 billion annually by mid-century. “From meatpackers to home health aides, workers are struggling in sweltering temperatures and productivity is taking a hit,” Coral Davenport reports for the New York Times.