Hello, and welcome to the last issue of Record High. I’m Zoya Teirstein, and today, we’re going to talk about the elephant in the room: heat inequity.

In his book Fevers, Feuds, and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History, the physician and medical anthropologist Paul Farmer explains, unflinchingly, why the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak killed more than 11,000 Africans while almost every single Westerner who contracted the illness survived. The difference between life and death came down to, quite simply, access. In clinics in Guinea, Libera, and Sierra Leone, equipment and fluids that would have saved countless lives were nonexistent. A few simple interventions would have made all the difference. “How many of these deaths were caused more by the virulence of social conditions than by the virulence of the pathogen?” Farmer asked.

I was reminded of Farmer’s book recently while interviewing a researcher about an unrelated topic, a study on the temperature thresholds at which the human body can no longer keep itself cool. That researcher, a scientist at the University of Oxford, found that parts of the world have already become too hot for human survival. As climate change accelerates, more portions of the globe will approach this threshold, what the study calls “the danger zone.” Whether someone dies in that zone depends in large part on their access to cooling strategies — such as fans, cold drinking water, and, of course, air conditioning.

Climate reporter Jeff Goodell writes extensively about this divide between the “cooled and the doomed” in his new best-selling book The Heat Will Kill You First. “There’s a profound gap in every city, everywhere, between people who have air conditioning and people who don’t,” Goodell told me in July, as Phoenix was experiencing what would become a 31-day stretch of 110 degree days — the hottest month in any U.S. city on record.

“There’s a profound gap in every city, everywhere, between people who have air conditioning and people who don’t.”

Heat is swiftly becoming one of the most formidable climate-fueled health threats of our time. It kills more people than any other extreme weather condition. Like Ebola and other deadly outbreaks in global history, it kills unequally. Finding this inequality in the United States is appallingly easy — just follow the racial boundaries that divide many cities and towns. Wealthy, white neighborhoods are less likely to experience deadly heat than non-white areas. A lot of these segregated communities are clustered in Southern states, among the hottest in the nation, and big cities that lack green space.

A recent paper published by the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory found that the average Black urban resident is exposed to markedly higher heat stress than the average white urban resident. On average, Black people are exposed to temperatures that are a little more than half a degree hotter than the city average, while white people live in areas that are a little less than half a degree cooler. Much of this temperature imparity — which leads to more hospitalizations and deaths within minority communities — is due to segregation and redlining. “The findings reveal pervasive income- and race-based disparities within U.S. cities,” the study’s authors wrote.

This newsletter may be winding down, but heat isn’t going anywhere. It’s likely that in the future, we’ll remember the summer of 2023 — the hottest on record — as among the coolest summers of this century. There are as many right ways to approach the challenge of a hotter world and its health impacts as there are wrong ways. Successfully mitigating extreme heat also necessarily means fighting inequalities in health, the built environment, and local and national government policies, which will determine who lives and who dies as the planet continues to warm. Any effort to address the impacts of extreme heat that doesn’t take that into account the “virulence of social conditions,” as Farmer wrote, isn’t much of a solution at all.

Today concludes our run of Record High, but our team still has a few big stories in the works. We’ll be using this newsletter to (very occasionally) let you know when those new projects publish over the next few months.

Thanks for sticking with us this summer. We’ll see you next time.

P.S. If you’d like to keep seeing Grist content in your inbox, sign up for our flagship newsletter — 10 of our newest stories delivered to you once weekly — here. And if you want to play a role in shaping next year’s extreme weather newsletter, fill out this audience survey. It takes just a few minutes.

By the numbers

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

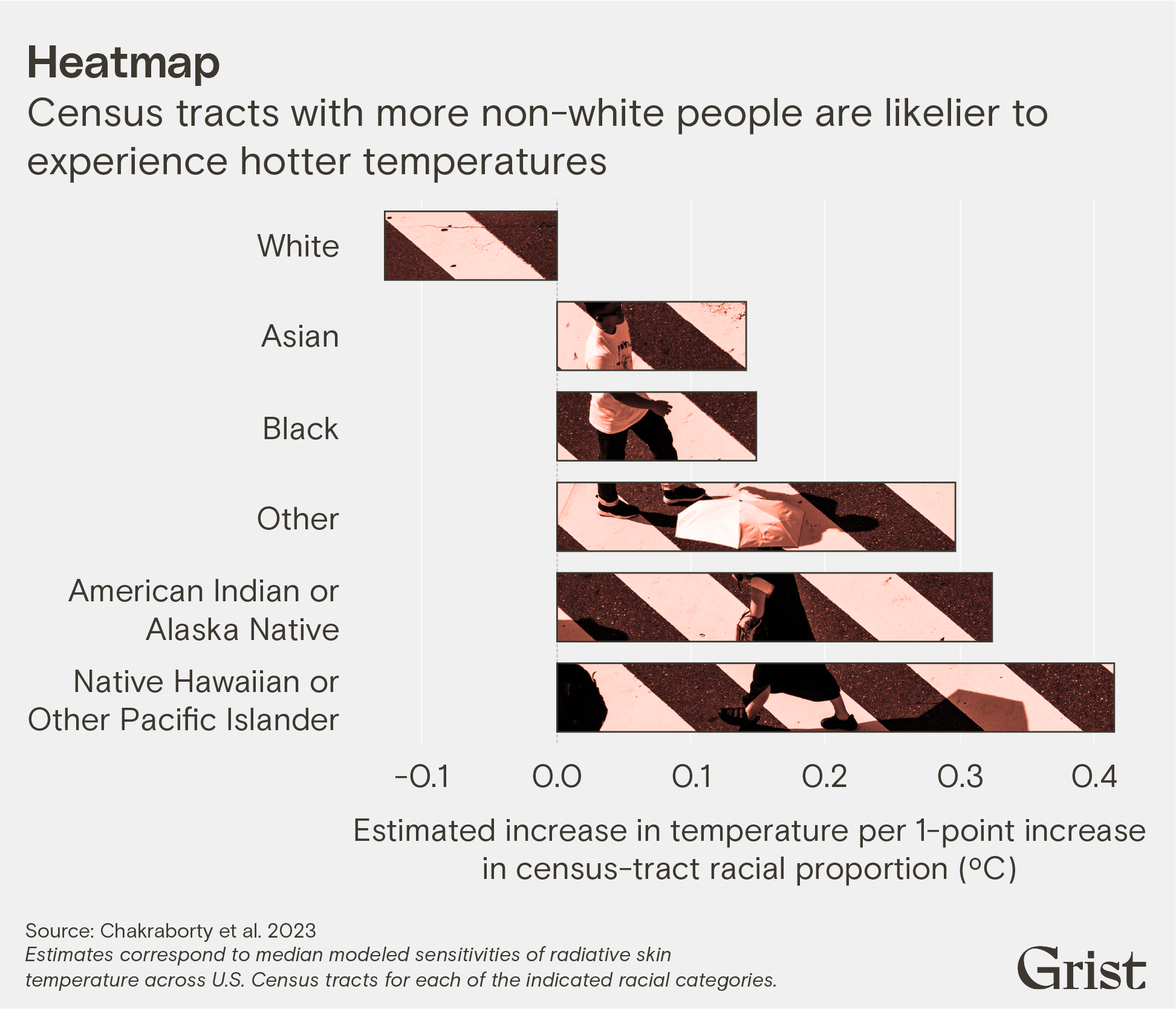

In the U.S., non-white populations are exposed to higher temperatures than white populations. Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders experience this disparity most acutely, but all non-white people are subject to elevated temperatures, while white populations experience cooler-than-average temps.

What we’re reading

The strange connection between alcohol and heat: A new study found short-term temperature spikes lead to marked increases in the rate of hospitalizations for alcohol-related disorders. Even a slight increase in temperature, say from 15 degrees Fahrenheit one week to 20 degrees F the next week, or from 60 to 65 degrees F, led to more hospitalizations for substance use.![]() Read more

Read more

South America’s hot winter comes to a close: And it’s 110 degrees in parts of Brazil. It looks like an enormous heat dome afflicting much of South America isn’t going away anytime soon. My colleague Max Graham writes about what the beginning of summer following a record-breaking winter means for the continent and the rest of the world.![]() Read more

Read more

This summer’s record-breaking heat in charts: Heat this summer has broken previous records “by a truly staggering margin,” Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at the Breakthrough Institute wrote in a blog post. Hausfather said there’s a chance 2023 will “emerge as the first year exceeding 1.5C above preindustrial levels.![]() Read more

Read more

The worst heat wave ever recorded happened in … Antarctica? A new study shows the most intense heat wave on the planet took place in Antarctica in March 2022, when temperatures on the continent spiked 70 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. Kasha Patel writes about it for the Washington Post.![]() Read more

Read more

Another victim of extreme heat: recess. Schools across the country closed early, trimmed recess, and canceled outdoor after-school activities altogether due to sweltering heat this month. This isn’t the first year kids have suffered at school due to rising temperatures, and the trend has experts worried. NPR’s Sequoia Carrillo and Beth Wallis have a great segment about the issue on All Things Considered.![]() Read more

Read more