This story has been updated.

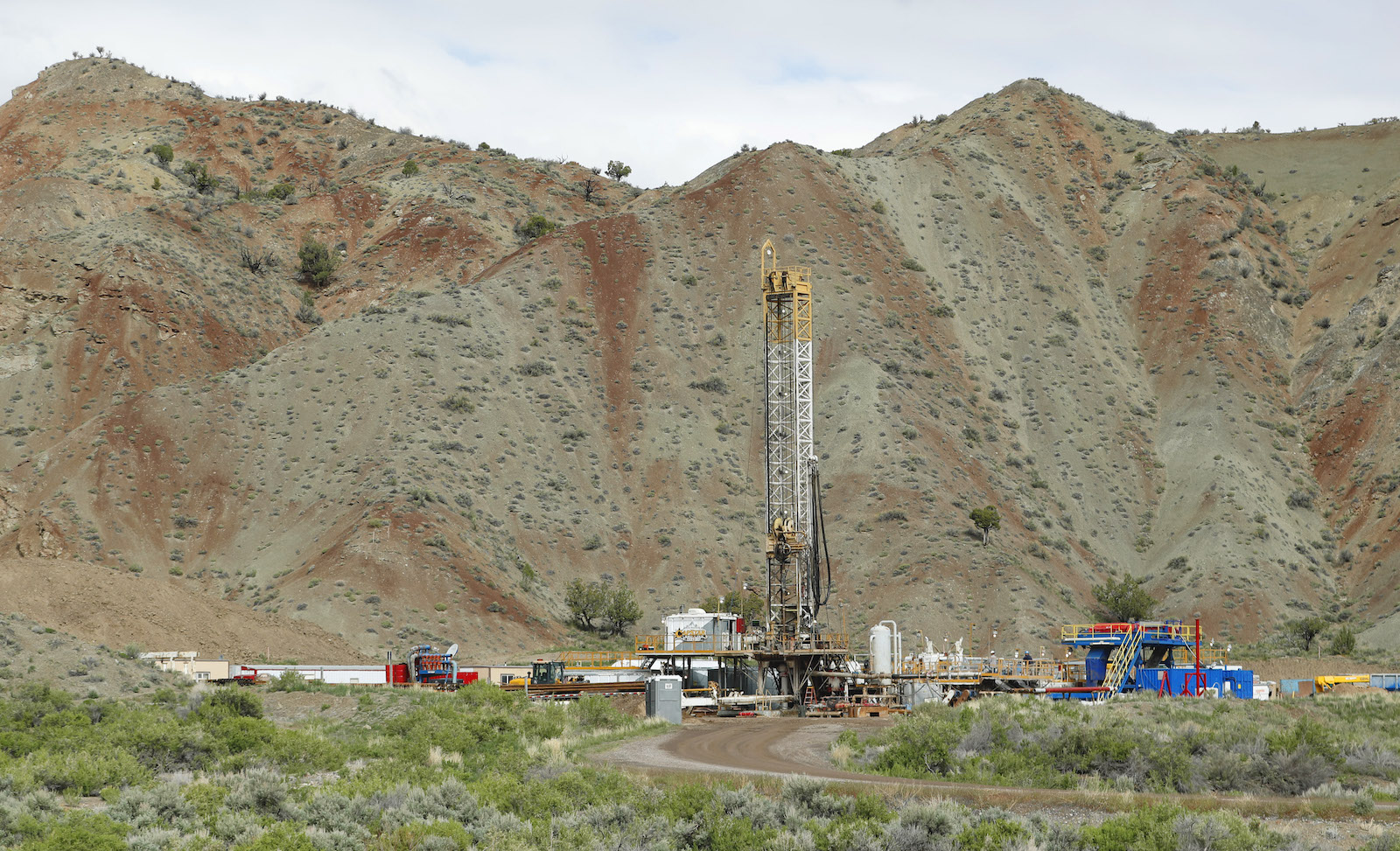

Joe Biden caused a big kerfuffle in the run-up to the 2020 election when he said during a primary debate that he supported “no new fracking.” Then-President Donald Trump’s campaign ran with the quote, accusing his Democratic opponent of wanting to abolish fossil fuels and kill jobs. But Biden’s plans for restricting oil and gas production have always been narrow. His debate remark was a slip of the tongue for the then-candidate who actually meant to say that he intended to ban new oil and gas permitting on public lands and waters, areas that account for only 6 and 8 percent of total American oil and gas production, respectively.

Since Biden took office, even that tentative step toward a fossil-fuel-free future has proven to be tough. The new president quickly announced a moratorium on the sale of drilling leases while the Interior Department conducted a review of the federal oil and gas program. But in the meantime, Biden’s Interior Department has been approving drilling permits for previously sold leases at a fast clip. It approved more than 2,100 permits in his first six months, a pace that surpasses monthly approvals during most of Trump’s presidency, according to the AP.

The leasing pause also came under attack in March, when Republican attorneys general from 14 states sued Biden, arguing that lease sales are mandated by Congress. In June, a federal judge in Louisiana sided with them, issuing an injunction against Biden’s moratorium.

This week, the Interior Department announced it would appeal that decision, while also resuming leasing in compliance with it. But what happens next is an open question.

For one, it’s unclear whether lifting the moratorium means the administration will begin selling leases anytime soon. The oil and gas industry and the states that filed the lawsuit argue that the Interior Department is required by law to hold quarterly lease sales for onshore drilling. But Kyle Tisdel, a senior attorney at the Western Environmental Law Center, told Grist that the law in question, the Mineral Leasing Act,* builds in “significant discretion” for the Interior Department, “including the ability to defer leasing as needed to complete necessary analysis and to not lease parcels where it determines other resource values should be prioritized.”

In its announcement on Tuesday, the Interior Department acknowledged that discretion and indicated it wouldn’t exactly be rushing to sell leases. “Interior will continue to exercise the authority and discretion provided under the law to conduct leasing in a manner that takes into account the program’s many deficiencies,” it said.

The statement enumerates the leasing program’s many problems, including its failure to consider the climate impacts of drilling or to incorporate the costs of climate change into royalty rates. Past assessments of the program have found that it frequently sells off drilling rights for less than $2 dollars per acre, allows companies to sit on leases for up to 10 years, and generates only a fraction of the revenue in royalties that drilling on state or private lands does. The department also noted its poor track record when it comes to consulting impacted communities, and its responsibility to balance its obligations under the Mineral Rights Act with other uses for public lands, like wildlife conservation and protecting historic and cultural resources.

One analyst told E&E News the statement struck a “defiant tone” that “reinforces our expectation for the Biden administration to look for other ways to pause leasing.”

The other unknown, besides how the Interior Department will conduct lease sales, is how long it will take the agency to complete its review of the program. It was originally supposed to issue an interim report on its initial findings early this summer, but that has yet to happen. A spokesperson for the agency told Grist that it does not have a new deadline or estimated time of completion. The report is expected to offer recommendations for the agency and for Congress “to improve stewardship of public lands and waters, create jobs, and build a just and equitable energy future.”

In the meantime, other recent developments at the federal level signal small shifts toward more stringent regulations of fossil fuels. On Thursday, a U.S. District Court Judge threw out key permits for a major oil drilling project in Alaska due to deficiencies in the environmental review conducted under the Trump administration, including its estimate of greenhouse gas emissions. Also on Thursday, the Interior Department made a long-awaited announcement that it will conduct a review of its program for leasing coal mining rights on federal lands. The review was first ordered by the Obama administration toward the end of his presidency, but Trump quickly halted it when stepping into office. The agency does not intend to pause leasing while it conducts its review, as it did with oil and gas.

* Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified the Mineral Leasing Act.