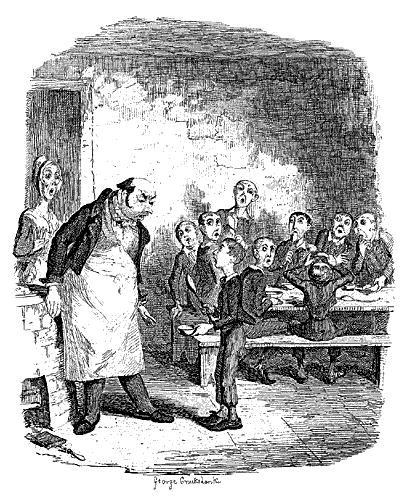

Scene from Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Drawing by George Cruikshank, circa 1837.At a time when many families are struggling with money — and racking up millions of dollars in debt at school cafeterias — school lunch is about to get more expensive. The hike is mandated by the recent Child Nutrition Reauthorization passed by Congress and signed into law by the president.

Scene from Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Drawing by George Cruikshank, circa 1837.At a time when many families are struggling with money — and racking up millions of dollars in debt at school cafeterias — school lunch is about to get more expensive. The hike is mandated by the recent Child Nutrition Reauthorization passed by Congress and signed into law by the president.

Schools that now charge only $1.50 for lunch would, over time, have to increase the price to at least match the federal contribution for a fully-subsidized meal — currently $2.72 — according to a provision in Congress’ recent reauthorization of the federally-subsidized school meals program.

The mandate for higher prices passed virtually undetected as the public debate over the school food bill focused on the measly six-cent raise Congress gave the program and some $2.2 billion lawmakers borrowed from the food stamp program to pay for it.

The measure is aimed at children who do not qualify as low income and pay “full price” for school lunch. Some have hailed it as a potential boon for school kitchens. The USDA estimates it would, over 10 years, generate some $2.6 billion in additional revenue — assuming millions of kids don’t opt out of the program and start bringing food from home. (Would you pay full price for the food most schools serve?)

The current practice of giving a price break to kids deemed able to pay is seen as unfair because it drains money that should be supporting poor children. One prominent food writer even suggested that bands of rich kids — with “parents making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year” — were mooching cheap food in schools here in the nation’s capitol. D.C. school officials would certainly like to know who those children are, since families making that kind of money typically send their kids to one of the private schools that proliferate here. Participation in the meals program drops sharply with higher income and family education level.

School boards objected to the proposal, saying the federal government has no business telling local officials how to price school meals and that raising prices could exclude many children who don’t technically qualify as “low income,” but still can’t afford more expensive cafeteria food.

The cost of complying with new federal meal guidelines that call for more fruits and vegetables, more whole grains, and less salt, may well force cash-strapped schools to raise the price of lunch and breakfast.

But what school districts are grappling with at the moment are too many students who don’t qualitfy for free lunch but who arrive at school without either a home-packed lunch or the money to pay up in the cafeteria. Typically, cafeteria workers let them eat, but record their unpaid dues as debt. In New York City, for instance, schools since 2004 have absorbed at least $42 million in unpaid lunch fees, and now principals are being told they must collect the money or have it docked from their budgets.

Of the city’s 1,600 schools, 1,043 owe a collective $2.5 million to the department for meals served in the first three months of this school year. That puts them on track to be $8 million behind by the end of the school year.

Under city rules, elementary and middle school students who are behind on payments but come to school without their own lunches must be fed the same meal as everyone else. High schools are not required to feed such students.

Similar stories are playing out in school districts across the country, reports the New York Times. In some cases, districts are imposing a kind of austerity on kids who can’t pay — and a kind of de facto stigma. Schools in Albuquerque have started serving cold sandwiches and milk, instead of full hot meals, to students whose parents fall behind on their bill. In Wake County, N.C., those students may eat as many fruits and vegetables as they want, but not the rest of the lunch offerings.

Framingham, Mass., hired a constable to collect money from parents, but the schools are still short $40,000. School officials make repeated phone calls to parents and send letters home, to no avail. “I struggle every day to recoup these funds — every day,” said Brendan Ryan, the school system’s food services director.

The School Nutrition Association (SNA), representing some 53,000 cafeteria workers across the country, reports that nearly 40 percent of its members saw an increase in unpaid meals in the last year.

School food advocates look to the federal government to pay for school meals. Instead, Congress, faced with its own budget crisis, is trying to pass the cost onto struggling state and local governments — and now onto parents unable to make ends meet.

A House version of the bill called for the price hikes to expire after 10 years and for the USDA to perform and impact assessment after four years. But in a frantic effort to pass the legislation before Congress adjourned last year, the Senate’s version imposing price hikes was adopted unchanged. The SNA says the feds need to take a second look and test the idea before forcing schools to raise prices nationwide. Given that an unemployment crisis seems to be settling in long-term, that seems a wise idea — if we accept the idea that every kid needs a decent lunch in order to learn properly.