In February, on the eve of the release of a major new report on the effects of climate change by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, several of its authors met with reporters virtually to present their findings. Ecologist Camille Parmesan, a professor at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, was the first to speak.

Scientists are documenting changes that are “much more widespread” and “much more negative,” she said, than anticipated for the 1.09 degrees Celsius of global warming that has occurred to date. “This has opened up a whole new realm of understanding of what the impacts of overshoot might entail.”

It was a critical message that was easy to miss. “Overshoot” is jargon that has not yet made the jump from scientific journals into the public vernacular. It didn’t make it into many headlines.

But just days earlier, the topic generated extensive debate when Parmesan and her coauthors went over their findings with government representatives from around the world. And next week, after the IPCC releases another big report on climate solutions, you may just start hearing about it more and more.

“Remember this word: overshoot,” Janos Pasztor, the executive director of the Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative and the former United Nations assistant secretary-general on climate change, wrote in an op-ed published in January. “It will gain increasing importance as the herculean difficulty of reducing emissions to net zero and removing vast stores of carbon from the atmosphere become clearer.”

The topic of overshoot has actually been lingering beneath the surface of public discussion about climate change for years, often implied but rarely mentioned directly. In the broadest sense, overshoot is a future where the world does not cut carbon quickly enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre industrial levels — a limit often described as a threshold of dangerous climate change — but then is able to bring the temperature back down later on. A sort of climate boomerang.

Here’s how: After blowing past 1.5 degrees, nations eventually achieve net-zero emissions. This requires not only reducing emissions, but also canceling out any remaining emissions with actions to suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, commonly called carbon removal. At that point, the temperature may have only risen to 1.6 degrees C, or it could have shot past 2 degrees, or 3, or 4 — depending on how long it takes to get to net-zero.

The global temperature will begin to stabilize, but it will not decline. So next, nations will aim to scale up carbon removal even further. This will lower the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and bring the temperature on earth back down below 2 degrees C, if not to 1.5, or even lower, by the end of this century.

This possibility of overshoot was first conceived by scientific models that map out potential pathways for climate policy. And in the realm of a computer model, overshoot is a success story. We may fail to meet global climate targets in the next few decades, but hey, we can always turn things around and achieve them by 2100. But Parmesan and other scientists are warning that overshoot should not be considered lightly. While the rise in temperature is theoretically reversible, many of the consequences of a temporarily hotter planet will not be.

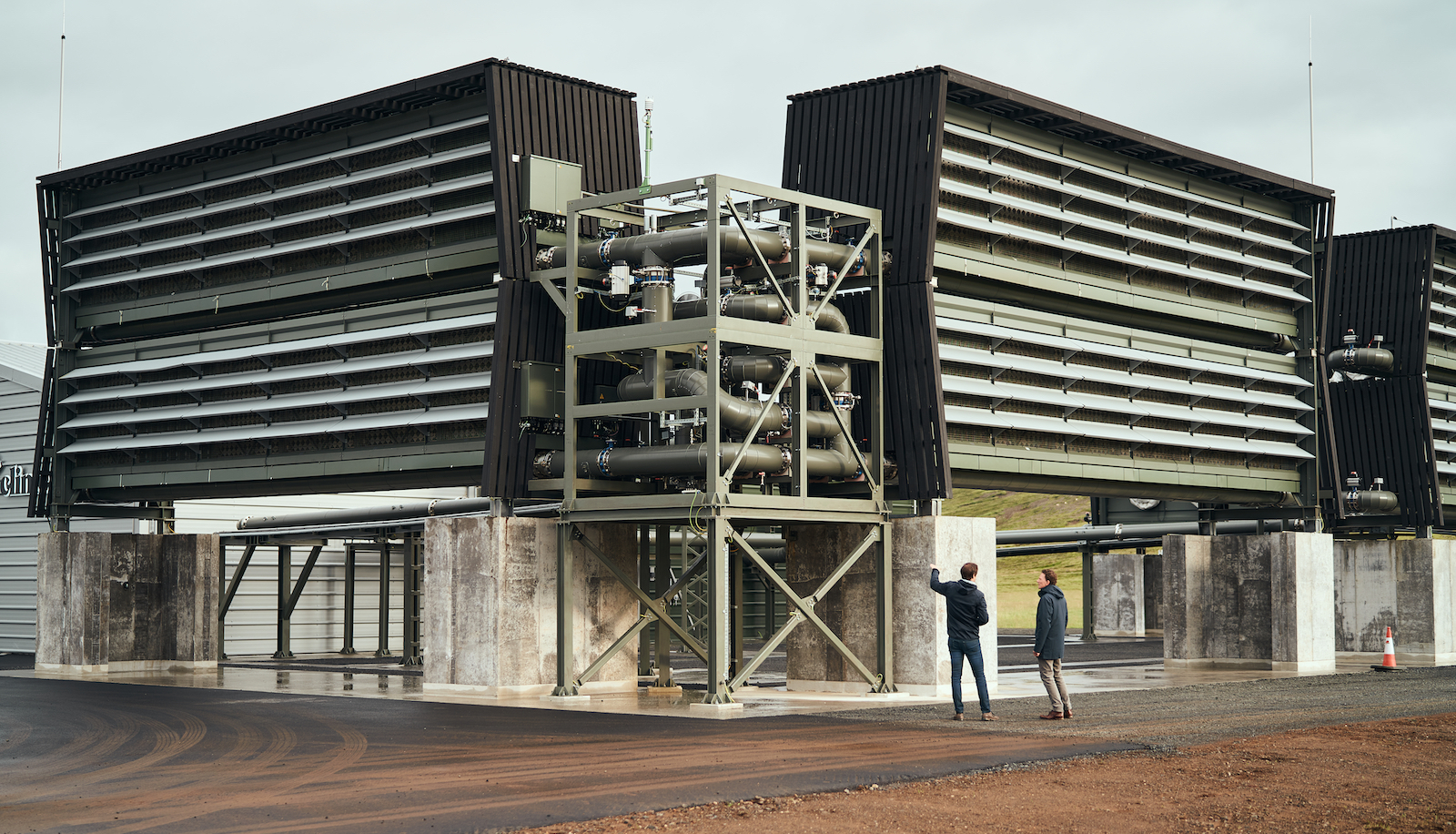

In a sense, we are on the pathway to overshoot right now. Warming is already dangerously close to 1.5 degrees, emissions are not going down, and existing policies put the world on track to warm 3 degrees by the end of the century. Policymakers are also beginning to seriously invest in carbon removal research and development, however, these solutions are still nowhere near being able to turn temperature rise around.

When I reached out to Parmesan to ask about her statement in the press conference, she was eager to talk about overshoot. “It’s so important, and really being downplayed by policymakers,” she wrote.

“I think there’s very much an increased awareness of the need for action,” she told me when we got on the phone. “But then they fool themselves into thinking oh, but if we go over for a few decades, it’ll be okay.”

The effects of overshoot could undermine climate solutions

The February report was part of the sixth major assessment of climate science by the IPCC, a body of hundreds of scientists convened by the U.N. The assessment is published in three volumes that look at the physical science of climate change, the effects of a warming planet on ecosystems and people and how to adapt to them, and the options for cutting emissions and removing carbon from the atmosphere. That third volume will be released next week.

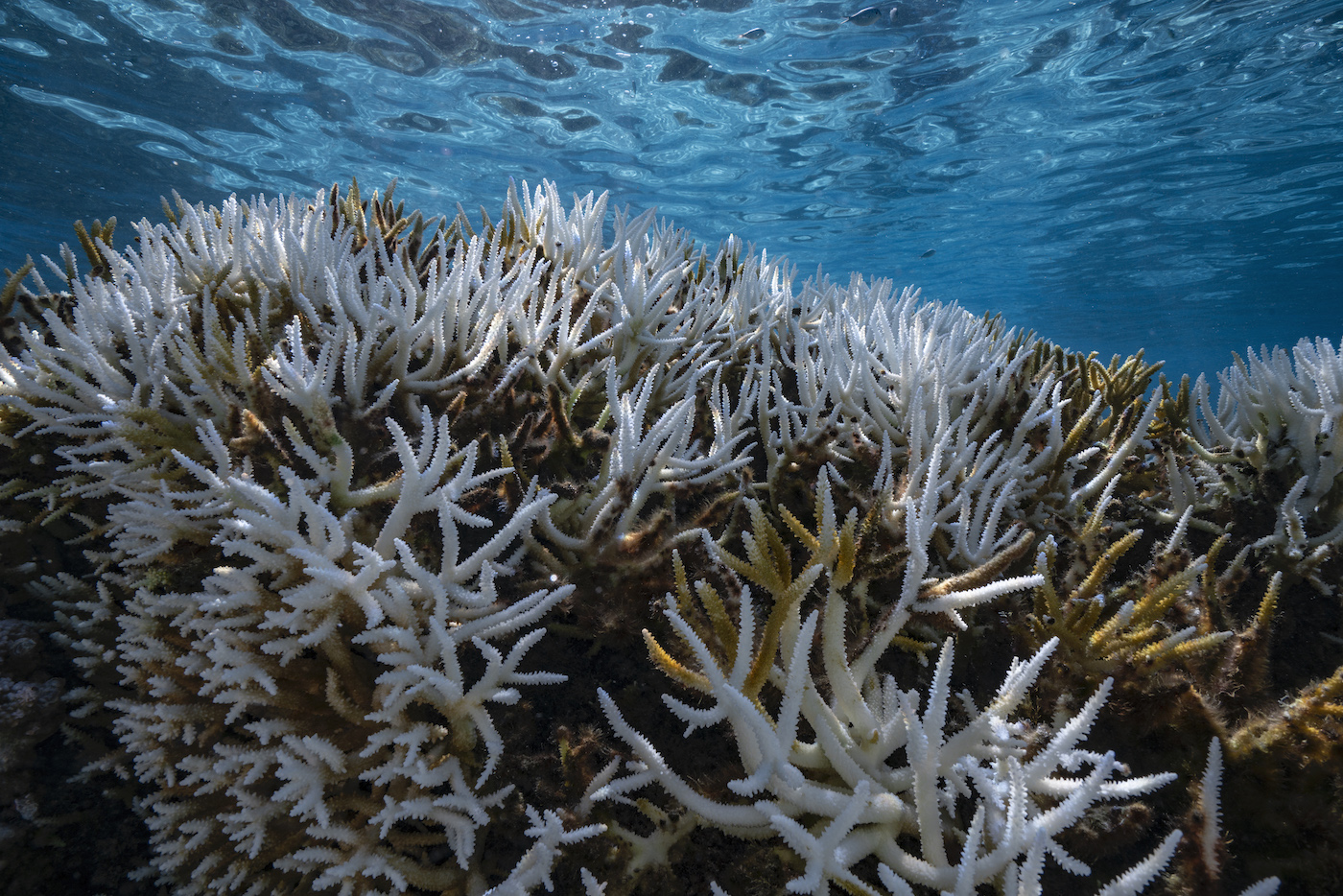

Parmesan said the IPCC’s recent impacts report shed light on two key risks of a future period of overshoot that she felt people were not paying enough attention to. The first is that some impacts will be irreversible, like the loss of coral reefs and species extinctions. “Global warming coming back down is not going to bring you that species back,” she said.

Though Parmesan did note that for many threatened species, “the shorter the overshoot, the lower the overshoot, the less likely they are to actually go extinct.”

Sea-level rise is also irreversible — the heat collecting in ice sheets and the ocean will continue to drive sea-level rise long after the temperature is stabilized or even lowered. Not to mention the possibility of losing entire nations and cultures to the sea, or the mass loss of human life from a world with more dangerous heat waves and storms.

But the second risk throws the whole possibility of eventually reversing global warming into question. This is the part that stirred up confusion and controversy prior to the IPCC report’s release, when scientists were going over their findings with government delegates.

It has to do with climate feedbacks — changes to natural systems caused by climate change that then exacerbate climate change. The report documents countless examples that scientists are already observing. Insect outbreaks and wildfires are killing trees, causing huge releases of greenhouse gases from forests. Heat and drought are causing some parts of the Amazon rainforest to release more carbon than they suck up — even in intact, old-growth areas that have not been disturbed by agriculture or development. Arctic permafrost — frozen, carbon-rich soil — is thawing and beginning to release the carbon stored within. Scientists estimate that there is five times as much carbon stored in permafrost than has ever been emitted by humans.

Scientists say it is still possible to stop or even reverse these feedbacks with aggressive cuts to fossil fuel emissions and by actively restoring ecosystems. Walter Oechel, a biologist at San Diego State University who first discovered that Arctic permafrost was becoming a net source of emissions in the 1980s, said that in northern Alaska, the permafrost is more than 1,000 feet thick, and for the most part, it’s just the surface layer that’s melting and releasing carbon. “But it’s going to get harder and harder to ameliorate or to reverse the longer we wait,” he said.

This is the crux of Parmesan’s second warning. Once some of these processes get chugging along, they may reach a point where it becomes impossible to stop them. “Humans can control human actions, but humans cannot control the biosphere’s responses to climate change,” she said. “And we’re witnessing responses that are going to make it harder and harder and harder for humans to get global warming down.”

If permafrost and rainforests begin pumping carbon into the atmosphere, the possibility of achieving net-zero, or even net-negative emissions would become a much bigger uphill battle. Even if we develop significant carbon removal capacity, these feedback emissions could make trying to remove carbon from the atmosphere feel like trying to shovel the walkway in the middle of a blizzard.

Scientists cannot pinpoint a specific temperature, or how long of an overshoot period may lead to unstoppable emissions from these systems. “But we can tell you these processes have already started,” said Parmesan. “And the longer they go on, the higher the warming, the longer the warming, the harder it’s going to be to reverse.”

Wolfgang Cramer, a co-author on the IPCC impacts report, said that when they explained this to government delegates, the discussion grew thorny. Some felt that talking about this would discredit the idea that we can aggressively cut carbon later in the century and reverse global warming. “It was seen as a way to be policy prescriptive,” Cramer said. “As if we wanted to tell them that if you don’t get it now then there’s no point in trying later.”

But to him that missed the point. “We’re just telling you that you may find it harder to come back later in the century than you think,” he said. “We were just making a case against delaying action.”

From models to policy

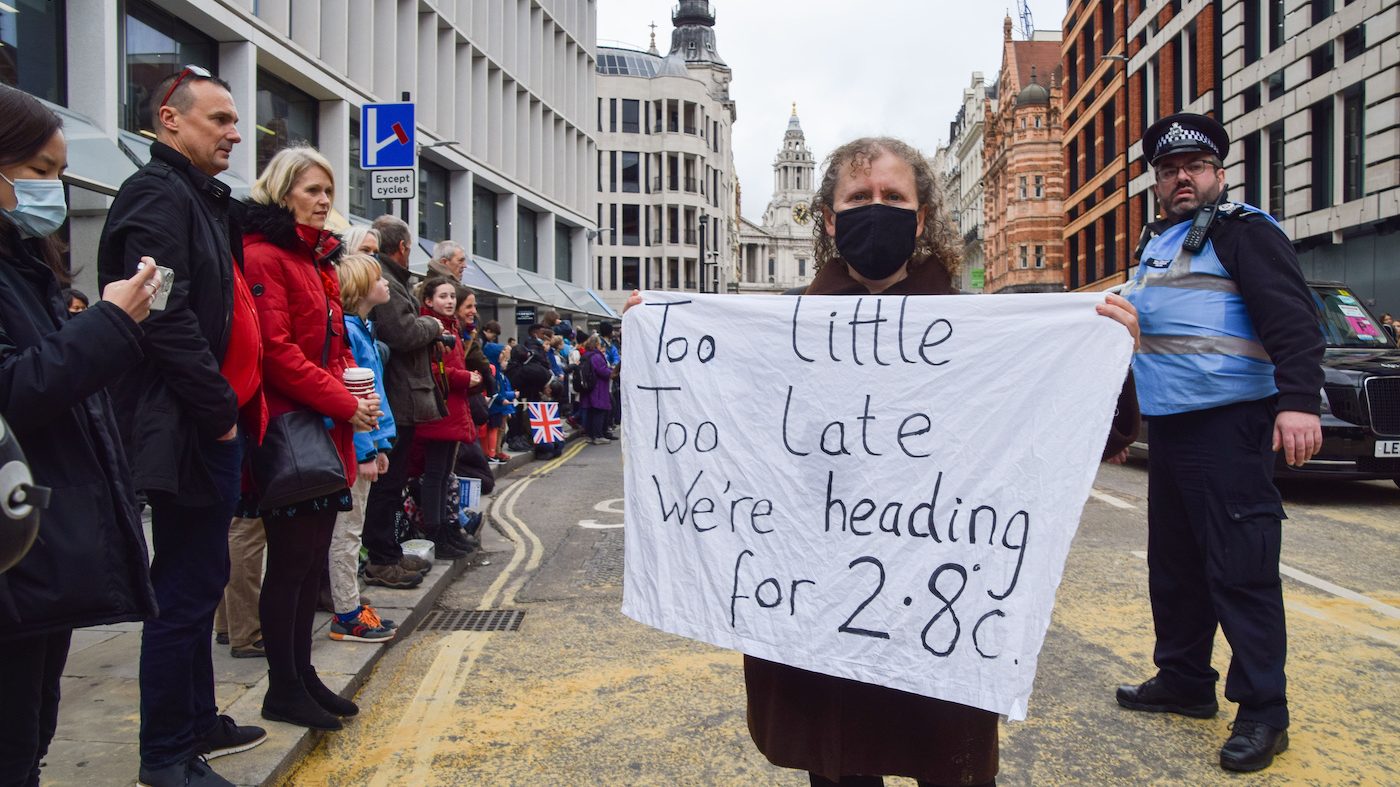

A future with overshoot is not some niche idea. Parmesan said the impression she gets from global climate talks like COP26 is that this is what some policymakers are planning for. “They have been talking about it as though okay, this isn’t great, but, you know, this is probably what’s going to happen,” she told Grist.

It’s unclear whether that was the case when world leaders signed the Paris Agreement in 2015, promising to limit warming to “well below 2 degrees” and “pursue efforts” to stay below 1.5 degrees. David Morrow, the director of research for the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy at American University, said it struck him at the time that 1.5 was an aspirational target, something that people took less seriously then than they do now.

“I think it was what climate ethicist Steve Gardner calls ‘bearing witness’ to our collective failure in climate policy,” he said. “It was small island states pointing out, 2 degrees is a death sentence for us. We are not willing to accept that and so we want you to acknowledge this 1.5 degree target.”

Keywan Riahi, director of the energy program at the Austrian research institute IIASA and a prominent climate modeler, speculated that 1.5 degrees would not have been on the table in Paris if it wasn’t for climate models that showed pathways to bring temperatures back down after a peak.

Overshoot scenarios dominate the climate modeling literature. In a 2018 IPCC report, researchers analyzed more than 200 modeled climate action pathways that would keep warming under 2 degrees by the end of the century. Only nine of them avoided going beyond 1.5 degrees. For those nine, it wasn’t even a sure bet — the likelihood of staying below that threshold throughout the 21st century was only 50 to 66 percent.

There are a few reasons for this. One is time. Morrow said modelers build in an assumption that climate action will ramp up gradually, rather than accelerate dramatically in the near term and then level out. We’re already dangerously close to 1.5 degrees, so that gradual process doesn’t do us any favors. And because the goal of these models is to achieve a specific temperature far away in 2100, they can make up for the slow start by ratcheting up climate policies, as well as negative emissions, later in the century.

Riahi said another reason was cost. The models are designed to find the most cost-effective way to achieve temperature targets. “The quicker we reduce emissions, the higher the cost will be,” Riahi explained, “because we have a lot of long-lived fossil-based infrastructure which would need to be prematurely phased out if we really try to accelerate and achieve zero emissions early.”

But now, modelers are beginning to try a new approach where instead of studying how to achieve end-of-the-century outcomes, they are looking at how to cap global warming at a specific maximum level. Last year, Riahi published a paper in Nature exploring the costs and feasibility of achieving temperature targets with no or limited overshoot. Contrary to the argument that gradual climate action is more cost effective, he found that the upfront investments needed to limit overshoot would bring long-term economic gains.

But these models, which are underpinned by climate science, still do not take into account the climate feedbacks that Parmesan and her co-authors are warning about. She said there’s still not enough data to plug those observations in.

That’s important to keep in mind next week, when the IPCC releases its next report on the topic of climate change mitigation. The report will evaluate our options for achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, with and without overshoot. It will also wrestle with the risks of presuming that we will be able to remove significant amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and evaluate the promise of various options for doing so.

Parmesan felt that the government delegates started out thinking she and her co-authors were exaggerating, but after two weeks of discussion, they started to get it. “They actually started realizing, Oh, we’ve seriously underestimated the risk of overshoot. And it’s like, yes, you have. That’s the whole point.”

It might not seem like a very challenging idea that climate change will bring irreversible impacts. Of course there are irreparable consequences of a future with more drought, heat, floods, and fires.

Cramer laughed when I put this to him. “You’re right,” he said. “It is actually not very complicated. You’re probably right that most people will understand it as soon as you talk to them about it. I think where there’s a sense in talking about it is to make people aware that the current engagement for reducing emissions is insufficient. We actually need to get emissions down now. Every 10th of a degree counts.”