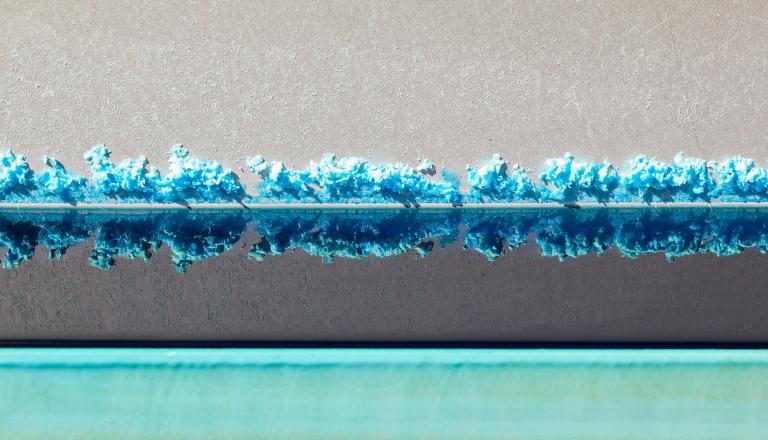

With intermittent sources like wind and solar becoming more common, energy storage is increasingly seen as crucial for greening the grid.Photo: mike_tnIn just about every story on renewable energy, there’s a familiar cast of characters: green power developers, utilities, and sundry state and federal regulators. But there’s one key player that often lurks in the background — the grid operator.

With intermittent sources like wind and solar becoming more common, energy storage is increasingly seen as crucial for greening the grid.Photo: mike_tnIn just about every story on renewable energy, there’s a familiar cast of characters: green power developers, utilities, and sundry state and federal regulators. But there’s one key player that often lurks in the background — the grid operator.

In the Golden State, most of the power grid is controlled by the California Independent System Operator. Based in a suburb of Sacramento, Cal ISO, as it’s known, essentially ensures that electricity supply and demand stay in balance to prevent brownouts, blackouts, and other catastrophic failures.

The agency also approves requests for big solar power plants, wind farms, and other renewable energy sources to connect to the grid. You may win approval for your project from the California Energy Commission and the United States Interior Department, but unless Cal ISO gives you the green light to plug into the grid, that big solar farm is nothing but a big white elephant.

The prospect of thousands of megawatts of intermittent sources of electricity like solar and wind jolting the grid — and then blinking off when a cloud passes overhead or the wind dies — poses a huge balancing act for grid operators. That’s especially true in place like California, which has mandated that a third of its electricity be generated from renewable sources by 2020.

So it was significant, if little noticed, when Cal ISO this month announced it would begin to integrate energy storage devices like batteries and flywheels into the grid.

Energy storage is increasingly seen as crucial for greening the grid. Electricity from wind farms, which in California typically generate the most power at night when demand is low, could be stored in giant battery arrays and released during the day when demand and rates rise.

Utility Pacific Gas & Electric, for instance, plans to store energy in the form of compressed air pumped into a cavern. When needed, the air would be released to power an electricity-generating turbine. The utility is also exploring using renewable energy to pump water uphill to a reservoir. When demand spikes, the water would be allowed to flow downhill and run a turbine.

Another utility, the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, plans to install lithium ion battery arrays at solar-powered homes to store electricity produced by photovoltaic arrays.

And last year, the California Legislature passed a law requiring regulators to determine if the state’s three big investor-owned utilities should be required to generate a certain percentage of electricity from energy storage.

Cal ISO’s early energy storage plans are modest, with just an initial 5 to 10 megawatts of storage integrated into the grid once federal officials given their okay. But it’s likely to be only the start.

“The integration of renewable sources introduces new requirements to reliably manage the grid,” Cal ISO’s chief executive, Yakout Mansour, said in a statement. “Our five-year strategic plan points out that storage technologies bring unique operational solutions to grid management as a tool for helping balance renewables on the system.”