This story was co-published with Alaska Public Media.

A dusting of snow clings to the highway as Barbara Schuhmann drives around a hairpin curve near her home in Fairbanks, Alaska. She slows for a patch of ice, explaining that the steep turn is just one of many concerns she has about a looming project that could radically transform Alaskan mining as the state begins looking beyond oil.

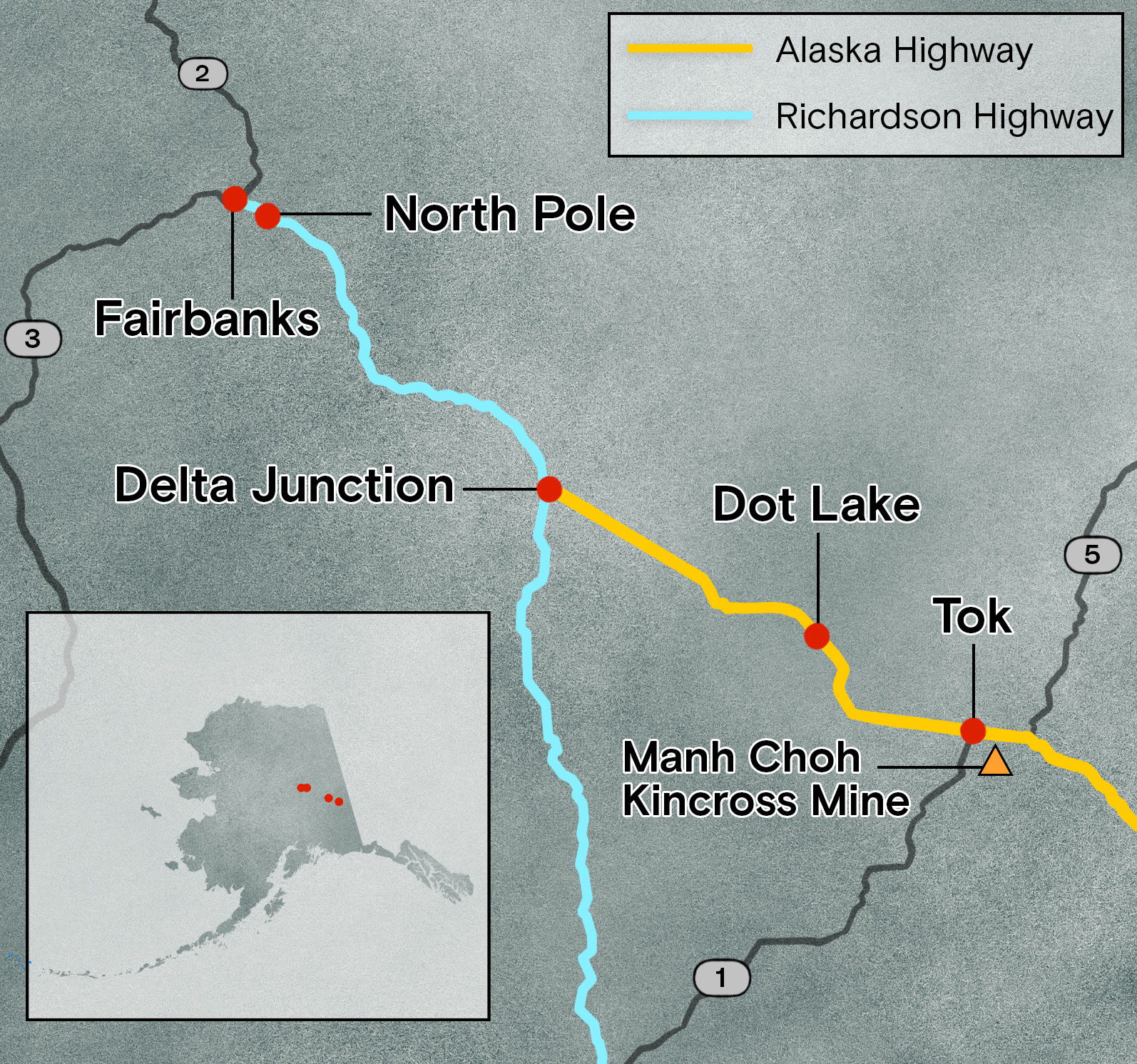

Roughly 250 miles to the southeast, plans are developing to dig an open-pit gold mine called Manh Choh, or “big lake” in Upper Tanana Athabascan. Kinross Alaska, the majority owner and operator, will haul the rock on the Alaska Highway and other roads to a processing mill just north of Fairbanks. The route follows the Tanana River across Alaska’s interior, where spruce-covered foothills knuckle below the stark peaks of the Alaska Range. Snowmelt feeds the creeks that form a mosaic of muskeg in nearby Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge, a migration corridor for hundreds of bird species.

When Schuhmann first heard about the project about a year ago, she was surprised. Kinross’ contracted trucking company, Black Gold Transport, will use customized 95-foot tractor-trailers with 16 axles, which will weigh 80 tons apiece when fully loaded. These trucks will soon rumble by homes and businesses every 12 minutes, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with trial runs starting this summer. “It sounded pretty crazy at the time, moving a mountain from one area of Alaska to another,” she recalls. “It just seemed unbelievable that this would be allowed without special permitting and safety considerations.”

She doesn’t often bring it up, but Schuhmann knows just how dangerous the road can be. Her husband lost his mother, brother, and sister on that highway when a truck crossed the centerline, hitting their car head-on. “So, accidents happen,” she says.

The risks go beyond traffic. The mine and its tailings at Fort Knox, the state’s largest gold mine, have the potential to pollute the air and waterways. But unlike most other mines in the state, there has been no environmental impact statement prepared for Manh Choh. Residents in communities along the route worry about the increased violence and housing shortages that often follow the arrival of such projects. Others question the state’s ability to impartially oversee the permitting process when it has invested $10 million from a state fund in the mine.

Kinross, which declined repeated interview requests and told others not to speak to Grist, says the project will create more than 400 jobs. Supporters point to the economic boost it could bring to the Native Village of Tetlin, which is leasing the land to Kinross, as well as to nearby Tok, home to 1,200 people.

But Manh Choh is just the beginning of a surge in mining projects in the state. While gold is not a critical mineral, Alaska holds large reserves of cobalt, copper, and rare earth minerals essential to the green transition. If Kinross is allowed to use public roads, it will set a precedent for other companies eager to expand — one in which significant health and safety risks are underwritten by taxpayers. Other looming projects, like the planned Ambler Road in the Brooks Range, are already quietly preparing to use the state’s highways.

Alaska is at a pivotal moment: Oil and gas production, historically the most important driver of the state’s economy, has been declining for decades. Mining, meanwhile, saw a 23 percent increase in production value in 2021 alone. As the Biden administration pushes to shore up domestic supply chains, Alaskans like Schuhmann aren’t the only ones questioning the race for minerals. She worries the state hasn’t taken the time to make sure that Alaskans can benefit from this kind of development — or at the very least, won’t be harmed by it. “They can’t answer the questions,” Schuhmann said. “And so we just keep trying to ask them.”

Lynn Cornberg adjusts her skis, tucking her chin into the wind. She sets off on a historic trail, just north of where gold was first discovered in Fairbanks in 1902, earning it the nickname “The Golden Heart City.” Spindrifts kick up behind her, crystalline in the below-zero chill. The snow darkens with dust as she approaches Fort Knox, where the original gold deposit is running out. After investing so much in the mine’s mill, however, Kinross is eager to keep it running by processing ore from other sites.

The rumble of huge machinery booms through the forest as the wind whips downhill toward Cornberg’s house. She worries about the risks the rock arriving from Tetlin might pose for her family. In addition to carcinogenic heavy metals, Manh Choh’s ore has the potential to generate acid. Such toxic effluent can continue for millenia. “It goes on generating acid forever,” Schuhmann says. “When you expose this sulfide to the air, it oxidizes. With a little precipitation, it turns to sulfuric acid that kills fish.” This pollution could be a problem not only at the pits in Tetlin, but from dust raised while crushing or transferring the ore to trucks; from whatever blows out of the big rigs on the road; or from processing, stockpiling, or storing the tailings at Fort Knox.

Stanley Taylor, the environmental coordinator for the Native Village of Tetlin, says some village residents were concerned about the risks, and the tribe intentionally outsourced some of the potential hazards to Fort Knox. As the Tetlin Tribal Council wrote in a letter to the Army Corps, “This plan only works because it uses existing infrastructure, the public highway system, and the mill at Fort Knox.” (Tetlin’s chief, Michael Sam, and its tribal council declined repeated interview requests.)

Given these concerns, the project’s environmental review has recently come under scrutiny. Permitting for Manh Choh falls to different state and federal agencies, and there has been no comprehensive look at the project’s full scope. When Fort Knox was first developed in 1993, Kinross conducted an assessment that did not require independent expert review, like an environmental impact statement would have. The permit issued then provided an umbrella for several other mines developed since, with few public details about their operations. Due to Fort Knox’s geochemistry, no one anticipated acid generation. Now, with Manh Choh, “I don’t think any of us [at the Corps’ Alaska district] considered that as a potential impact, that they’re bringing a different type of ore to the mill,” says Gregory Mazer, the project manager for the Army Corps of Engineers.

The Corps’ own review focused on a 5-acre area of wetlands around Manh Choh that did not include the trucking corridor and the tailings at Fort Knox. Both the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service criticized that decision. The EPA pointedly noted that many other hard-rock mine projects in Alaska have required an environmental impact statement, which “established a precedent which we recommend be considered.” It also suggested that “this project would greatly benefit from a more thorough review.” Both agencies warned about mercury, arsenic, and other heavy metals contaminating waterways, and about the mine’s effect on wildlife, including salmon that spawn in nearby waterways like the Tanana and Tok rivers.

This strategy is known as segmentation, or “dividing up projects so that each little facet of it would have no significant impacts,” says Robin Craig, a professor at the University of Southern California Gould School of Law. “Normally tailings are part of a mining permit,” she says dryly, and “historically in Alaska, tailings affect water quality.” A recent analysis of court cases by environmental law professors at Lewis & Clark Law School argues that the Corps’ pattern of narrowly reviewing projects is inconsistent with the agency’s own National Environmental Policy Act regulations. “Alaska is kind of infamous for letting mining go, regardless of the environmental impacts,” Craig says.

When Schuhmann filed a federal record request in the winter of 2022, for example, she learned that even the agencies involved in the mine’s permitting didn’t have all the information needed to assess its impacts. Kinross had given the Army Corps of Engineers a geochemical report detailing Manh Choh’s potential for acid generation — but experts at U.S. Fish and Wildlife didn’t know about it until Schuhmann gave it to them.

The state Department of Natural Resources routinely publishes links to permits, leases, and environmental audits for other mines, but Schuhmann was the first to share the documents publicly. “I have never considered myself an environmentalist. I mean, my whole working life, I was trying to help people develop their property,” she says. But now, “I am flabbergasted.”

Despite these concerns, Kinross is only required to monitor for acid generation for five years after mining is completed, after which the state will review its condition — a period Craig says is far too short for a problem that can last thousands of years. (The Department of Environmental Conservation says it is limited by state regulations to five-year permits.) Unlike many of the Western states now struggling to deal with acid leaching, she adds, “Alaska is actually in a position to prevent future, lingering, avoidable harm.”

But the state, which has invested $10 million in Manh Choh via Kinross’ junior partner Contango ORE, has been very supportive of the project. One of the trustees involved in managing that state fund, Jason Brune, also leads the agency responsible for issuing Kinross’ waste management permit. (In March, Alaska’s Permanent Fund Corporation board of trustees banned in-state investments to avoid future conflicts of interest.) “Regulatory agencies follow the politics of the administration they work for,” says Dave Chambers, founder of the Center for Science in Public Participation, a nonprofit that provides technical assistance on mining.

And in Alaska, the current administration is decidedly pro-development, a point Governor Mike Dunleavy — who fired an employee for refusing to sign a loyalty pledge — made in an interview with the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner last winter. “There’s too much ‘no.’ No trucks on the road from Tetlin to Fort Knox, no West Susitna Access Road, no Ambler Road,” the governor said. “I need Alaska to say yes to everything.”

Every year as the ice breaks up across Alaska’s vast Interior, caribou travel from their winter range near Tetlin to their calving grounds. Their tracks crisscross the crust along the highway into Tok, where another kind of migration is under way: White trucks flying orange safety flags zoom into the gas station and pull into Fast Eddy’s, the sole restaurant. Though Kinross isn’t yet processing ore, crews are building a gravel road to the site, where the company has started working. It recently bought a shuttered motel to use as a “man camp,” or employee housing. The wood on its tall, locking fence — built in response to locals’ concerns about the influx of workers — is still raw.

Down the road, Bronk Jorgensen’s log house offers a view of the hill, bristling with dark trees, that will soon be dug out. He grew up in Tok, flying over old claims in the back seat of his dad’s bush plane. It’s always been a “passing-through town,” Jorgensen explains. Tok began as a camp for the construction of the highway during World War II, and eked out a few more jobs when the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was constructed. Now, it’s a stop along what remains the only road to the Lower 48. “This will be the first real industry this community and area has seen on any scale,” he says.

Jorgensen concedes the increased traffic may be inconvenient, but says gold is a commodity, like any other already carried on the road. “If we as a society want to keep living the lifestyle that we live — between electric cars, iPhones, TVs — you know, we need a lot of minerals,” he says. He works a family placer mine, a small-scale operation that extracts gold from a stream bed, and argues that Alaska has far better safety records and environmental standards than other parts of the world. “If we’re going to be consuming these items, we should be responsible and producing them.”

Given his experience moving equipment into remote locations, Kinross hired Jorgensen’s company to help construct the road connecting the mine site to the highway. “Kinross has been very generous in making sure local contractors have had an opportunity to bid part of the work,” Jorgensen says. “The trickle-down economics of this project is going to be huge.”

Communities around Tok are hopeful Kinross will offer coveted year-round employment. The Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development recently awarded a $300,000 grant to train residents for potential jobs at Manh Choh. But Larry Mark, one of several hundred Tetlin tribal members, says, “What I’d really like to see is the tribal members have the first priority on jobs. We see all the non-tribal members getting hired left and right.”

Mark also questions the royalties Tetlin will receive from the project, which are set at a range of 3 to 5 percent. Elsewhere in Alaska, similar endeavors often offer much higher rates, as well as partial ownership. Red Dog, for example, is a large zinc mine leased from the Iñupiat in northwest Alaska, who now receive 35 percent of its net profits. Over half of its employees are tribal members.

Tetlin is in a unique position: Unlike other tribes, it retained its subsurface rights under the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, and negotiated the lease of its land to Kinross directly. “You have small communities with limited resources, responding to large companies with unlimited resources. And it’s very much an imbalance,” says Bob Brean, the former president of the native corporation of Tanacross, a tribe to the west of Tetlin. He spent decades negotiating surface deals for Tanacross with multinational companies like ExxonMobil. He learned the hard way to always demand a profit-sharing formula. “Alaska is still subjected to colonization techniques by big industry,” he says.

Though some tribal members remain enthusiastic about what Manh Choh money could bring to Tetlin — where most of the 130 village residents lack running water or sewer systems — Mark doesn’t feel the village is getting its fair share. “You got to benefit the tribe,” he says, frowning, “and it’s got to be in writing.”

Today, Mark lives in Tok with his adult sons, who come and go as he watches a basketball game, wearing moccasins with a hand-beaded Pittsburgh Steelers logo. “I grew up without electricity,” he says. He learned Upper Tanana Athabascan as his first language, traveled by dog team, and spent his winters trapping. “We’re the richest people there is. We have all the land, we have all the animals — we have everything.”

But Kinross’ bulldozers ran over his traps, costing his family thousands of dollars. Tribal members hunting a moose were recently thwarted by Kinross employees when the animal crossed the company road. Mark worries the ongoing construction will scare away the game his family relies on, especially if Manh Choh is just the beginning of renewed mining in the region. As the price of gold hovers around all-time highs, many old claims, like those scattered through the hill country north of Manh Choh, have become profitable again. “You ever see a miner stop looking for gold?” Mark asks. “They’re going to move to the next hill.”

Forty-five minutes west of Tok, over rippling frost heaves and past the skeletons of wildfire, sits the Native Village of Dot Lake. A northern harrier hovers near the small cluster of buildings, its cinnamon belly flashing as it circles, listening for prey. Tracy Charles-Smith, the president of Dot Lake’s tribal council, says Kinross recently asked to speak with the tribe about employment opportunities. She said no. “We don’t have people that want to work in their mine,” she says. “They apparently buy pizza for everybody and whatever. But we can buy our own pizza.”

Traffic blows by Dot Lake’s school at 65 mph. “My tribe is very concerned with cultural and social impacts [of Manh Choh], especially when it has to do with murdered and missing Indigenous women,” Charles-Smith says, citing research that suggests man camps can lead to greater incidences of sexual violence. “We’re pretty much expecting there to be an increase in victims,” she says. The closest hospital that can handle rape cases is 155 miles away in Fairbanks; Charles-Smith says it can take tribal members hours to get there. As a result, Dot Lake is in the process of creating a sexual assault response team.

Alaska already has an ongoing critical shortage of law enforcement in rural areas, and getting a timely response can be difficult. “The increase in the population alone is going to mean that there’s less opportunity for police to respond,” she says.

Other safety questions loom over the route as it winds from Tok to the urban centers of North Pole and Fairbanks. It’s primarily a two-lane ribbon of pavement with few passing lanes, and there are no alternative roads — for many, it’s a lifeline to a hospital, airport, or grocery store. The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities has made plans to fast-track the replacement of five bridges along the way, including two that the agency says are specifically to accommodate the ore haul. The Federal Highway Administration recently took issue with Alaska’s ratings standards for bridges. Alaska is the only state with no maximum load limit, which could result in trucks carrying more than the federal agency allows, possibly damaging structures over time. (The state has agreed to a plan with the federal agency to come into compliance.)

The DOT brushed away Barbara Schuhmann’s questions about these bridges last fall. During that same timeframe, the agency’s staff was working on a weekly basis with Kinross to provide engineering support for the project. “It’s kind of disconcerting that they’ve worked so hand-in-glove with Kinross, and yet they’re not forthcoming with the public,” Schuhmann says.

Three of these bridges were built during the 1940s. Their replacements aren’t likely to be completed until 2027. One of them is so narrow that the local custom is to wait for oncoming traffic to clear before starting across. The Department of Transportation places the price of the infrastructure upgrades at more than $317 million. None will be completed before the first trucks roll later this summer, or even before the mine reaches full production next year.

Retired DOT engineer Bob McHattie, who oversaw this stretch of highway during his decades at the agency, says that based upon his experience with haul roads, ongoing maintenance will add to those expenses — a point the agency concedes. Kinross will increase traffic on the road by as much as 20 percent. “Those big trucks will be the highway traffic between the mine and Fairbanks,” McHattie says. “Those will be the vehicles that are wearing out the road.” In states with less permissive load formulas, he believes, based on his experience, that “it probably wouldn’t be legal.”

The DOT says it doesn’t know how much this will ultimately cost Alaska, which has a budget crisis. To help pay for safety measures like additional plowing, the DOT could levy a toll on trucks using regulations already on the books. Kinross, meanwhile, has suggested the state increase its fuel tax on the general public.

Feeling like state officials were not taking these concerns seriously, Schuhmann helped form a group called Advocates for Safe Alaska Highways. Its members make unusual allies, with viewpoints spanning the political spectrum. Most, Schuhmann hastens to add, support mining. “We’re not out to get anybody, we’re not anti-mining,” she says. “We just want some common sense and safety to be injected into the whole situation.” Among balloons left over from her granddaughter’s birthday party, piles of paperwork have taken over a corner of her kitchen table. “From the beginning, we’ve asked, ‘What’s your transportation plan? What’s your safety plan?’ And we’ve never seen it in writing,” she says.

After much pleading from Advocates for Safe Alaska Highways, the DOT hired consulting firm Kinney Engineering to study the potential impacts to roadway infrastructure and safety. The assessment likely won’t be completed before the ore haul begins, but preliminary findings suggest the added traffic will increase crashes. In addition to road conditions, Kinney will also examine factors like the rise in air pollution. Coal-fired power plants, wood-burning stoves, and frequent air inversions have left the Fairbanks North Star Borough with some of the worst air in the country. The Environmental Protection Agency recently warned the borough it may lose $37 million in federal highway funding each year if it doesn’t come into compliance — just as the haul trucks and their emissions hit the road. “At this point, we really do not have the problem defined well enough to come up with solutions,” says Randy Kinney, founder of Kinney Engineering.

These concerns prompted the North Pole City Council and the Fairbanks North Star Borough Assembly to pass nonbinding resolutions opposing the ore haul last winter, although the borough’s language was softened after a new assembly member received a torrent of angry calls from fellow Republicans. A Kinross representative attended the borough meeting as it was being discussed and reminded everyone that the company is the community’s largest taxpayer. “I asked, ‘Oh, do you think we should treat people differently if they pay more in taxes?’” recalls assemblymember Savannah Fletcher. The opposition was symbolic anyway, she says. “We don’t have the ability to limit who can use these public roadways.”

Schuhmann argues that the length of the trailers that will haul the ore normally would prohibit Kinross from using the planned route. (The agency claims a clause in state transportation regulations allows long combination vehicles like those Black Gold Transport will deploy to use several primary roads through the heart of Fairbanks. Schuhmann counters that another regulation provides sweeping authority to keep any vehicle off the road in the interest of public safety.) Kinney estimates the ore trucks — passing a dozen traffic signals, over 100 school bus stops, and many driveways through Fairbanks and all along the route — will need at least 365 feet to come to a stop during the winter. Meanwhile, drivers experienced with Arctic roads are already in short supply; the Alaska Trucking Association estimates that the state is currently 500 short of its needs.

If these trucks have to brake rapidly, they run the risk of jack-knifing, or having the trailer spin forward of the cab. To explain the potential risks, DOT veteran McHattie wrote a tongue-in-cheek poem about Santa’s sleigh running into just such a rig near Dot Lake. “There lies Santa, buried by ore,” he wrote. “Just let the alternative sink into your head. It could have been you and your family instead!”

The dark humor helps with his cynicism. “They’re going to kill folks on my highways,” McHattie says. Though he’s a staunch conservative, joining Advocates for Safe Alaska Highways has changed his general outlook, especially “on things that can hurt people.” Later, he pulls out a gold coin. It’s cold and surprisingly heavy. Since Kinross has obtained the necessary permits, he’s fatalistic about the group’s chances of stopping the project. “People have been killing each other for thousands of years over gold,” he says. “This up here is just a much, much watered-down version.”

Fort Knox’s pit is so deep it’s difficult to see the bottom, even when flying overhead in a two-seat Cessna. The scars of old placer mines are pockmarked by recent exploration holes, as Kinross expands its footprint. The ore from another new — and also potentially acid-generating — deposit stands out, a darker brown framed by snow.

Alaska’s mines produced $4.5 billion worth of minerals last year. But mining contributes less than 1 percent of state revenue, which in 2021 came to $83 million. The base tax structure for that sector has remained largely unchanged since Alaska became a state in 1959. “There’s probably a lot of merit in revisiting many of the tax structures we have in the state of Alaska,” says state Representative Ashley Carrick, noting that Kinross and its supporters have worked to emphasize mining’s role in the region’s economy. “We have to really think about how we balance the past and current industries with what we want the long-term future to look like,” she adds. She notes, for example, that using highways as haul routes is in direct conflict with the tourism industry. Yet, she says, “Kinross and Contango do not seem moved by the public outcry.”

Questions about the role mining will play in Alaska’s economy grow increasingly urgent as companies use the lure of rare earth metals as an excuse to fast-track mine permitting. The U.S. Geological Survey has recently announced a $5.8 million initiative to map the state’s critical minerals, including rare earth deposits like cerium and yttrium as well as minerals important to renewable energy, like cobalt and copper. The governor is currently pushing to take control of wetland permitting from the Army Corps of Engineers, which would allow state agencies to expedite new projects. “It’s going to cost the Alaska taxpayers a fair amount of money,” says Dave Chambers of the Center for Science in Public Participation. He’s concerned that the state lacks both the budget and the technical expertise required. “Unfortunately, there’s no law against being stupid.”

Federal mining law isn’t much better. It was last updated in 1872, prompting U.S. Representative Raúl Grijalva of Arizona to introduce legislation in the spring of 2022 that would modernize a “severely antiquated” statute. The bill would require hard-rock mines to meet similar standards as oil and gas companies on public lands, establish royalties for operations, and conduct meaningful consultation with impacted tribes. (Nearly one-third of the mineral resources needed for the green energy transition are on or near Indigenous land.)

“If Alaska is transitioning to a mining-based extractive economy, they certainly need to review the percentage of benefits that the public gains,” says Mike Spindler, a former national wildlife refuge manager with decades of experience managing natural resources. “We do need jobs, we do need an economy, we do need critical minerals,” he acknowledges. But he wants it to be done responsibly. Many metals — including gold, which plays little part in the green energy transition — are easily recyclable. Developing alternative technologies, such as sodium-ion batteries, could also reduce the need for virgin materials. Instead of focusing on new extraction, using materials efficiently and revisiting existing tailings, which often have unutilized minerals, could reduce impacts.

But rather than modernizing, Manh Choh is setting a return to an era of deregulated mining, says Jeff Benowitz, a Fairbanks-based geologist. Contrary to industry best practices, for example, Kinross has not conducted seismic evaluations at Manh Choh. Earthquakes could have significant impacts on the mine’s hydrology, affecting where acid drainage might migrate. His comments during the public process pointing out these flaws were dismissed by the agencies issuing permits. If Alaska doesn’t do its due diligence, he says, it’s “a problem for the country — the whole United States of America. Because if you can do unregulated mining, why wouldn’t you?”

Mining companies are currently eyeing many other deposits along Alaska’s roads to make it much easier to transport their ore — including the Parks Highway, the state’s primary highway, which runs from Anchorage to Fairbanks. Kinross itself has been open about its intention to use public roads to develop other deposits, telling an industry publication there’s “an economic radius around Fort Knox, given the mill capacity, that makes a good chunk of Alaska attractive.”

There’s a near future in which many companies are trundling ore alongside tourist RVs and family minivans, compounding the risks. Yet Benowitz has a realistic view about how much outrage Manh Choh’s haul will generate — it’s so far away, most Americans can’t even picture the problems it poses. “I try not to be like, ‘No one cares about the school children, no one cares about air pollution in North Pole or Fairbanks, no one cares about the local fish,’” he says. “But they’re going to care when that’s in their state, and in their county.”

As a working geologist, Benowitz is concerned about the repercussions questioning the Manh Choh project might have on his career. “But eventually, when you see something that’s really wrong, you have to speak up. The precedent this is setting for the state of Alaska — and for the country — is horrific.”

Schuhmann also worries about backlash. She’s warned her daughter not to mention the mine in public, and to be cautious when she goes out with friends. Billions of dollars, she knows, are at stake. But she isn’t quitting. Schuhmann sends off another email to the state assistant attorney general about DOT regulations. She gives frustrated scientists matter-of-fact advice on appealing the permitting process. She tries to stay focused on the law that ought to be followed. “I don’t believe in getting angry over cases,” she says. “What’s the impact going to be for Alaskans? Those are the issues, not how I’m feeling.”

But one overcast spring day, Schuhmann walks along the Chena River with her granddaughter, watching as the season’s first trumpeter swans land in the newly open water. They pause by a bridge that 160,000 pound mining trucks will soon be crossing. “Do these companies ever really reconsider?” she asks, finally showing her exasperation. “I don’t know. It’s hard not to get depressed.”

We stand there in the snow until our toes get cold, watching as the swans front and bicker like politicians. By then, Schuhmann’s back to business. “We’ll have to just keep our thinking caps on.”

Lois Parshley is an investigative journalist. Read more of her work @loisparshley. This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.