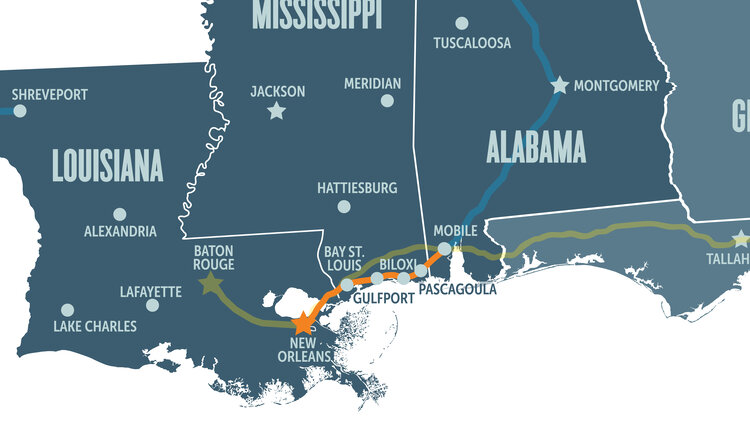

Ever since Hurricane Katrina swept across the Deep South in 2005, shredding the region’s railways, it’s been impossible to take a train heading east from New Orleans to the rest of the Gulf Coast. For years, Amtrak has been trying to restore service in the form of a twice-a-day line between New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama. But it’s met fierce resistance from two rail giants — CSX and Norfolk Southern — which own most of the tracks that the agency wants to use.

The freight companies argue that, without significant changes, any resumption of passenger services would ensnare their routes with traffic, sending costly delays down the country’s supply chain at a time when businesses are already plagued by shortages and slowed shipments.

The dispute is before federal regulators, with hearings set to restart May 9, and experts say their ruling will have far-reaching implications for the future of passenger rail in America. President Joe Biden, once known as “Amtrak Joe,” is eager to boost rail, allotting Amtrak $66 billion of last year’s infrastructure package. That would help cut emissions from transportation — the U.S.’s biggest source of greenhouse gasses. But any growth in rail service will need to take place on privately owned railways.

Advocates for public transit worry a loss could embolden freight companies to stymie passenger rail service elsewhere. “If CSX and Norfolk Southern are successful in blocking this, then dreams of expanded passenger rail will begin to wither and die in every part of the country,” said John Robert Smith, previously the mayor of Meridian, Mississippi, and now chairman of the advocacy group Transportation for America.

Clashes between Amtrak and freight companies are common, but the battle over the Gulf Coast line has inspired new tactics. In response to CSX’s claims that the New Orleans-Mobile line would seize up busy rails, Amtrak live-streamed the train stop in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, on Twitch last month. The camera offered a halcyon scene, reminiscent of a time when people took trains to beach towns for the weekend. From 8:00 a.m. to 3:33 p.m., birds chirped and the Gulf of Mexico beckoned behind mostly empty train tracks. Amtrak counted four trains in nearly eight hours.

Passenger trains are supposed to get the right of way on the tracks. In 1970, Congress created Amtrak, relieving private railroad companies of cash-bleeding passenger services. In return, the companies would give Amtrak priority on their railways — so long as it didn’t “unreasonably impair” business. Today, the government-chartered corporation owns just 3 percent — mostly in the Northeast — of the 21,400 miles it covers, so it has limited control over scheduling. According to Amtrak, freight companies rarely give passenger trains priority. Delays are common, and most of the time, freight trains are the culprit.

CSX and Norfolk Southern say running passenger trains east from New Orleans would interfere with their schedules in the Port of Mobile, where rails shuttling coal, grain, timber, and more, weave along the river that spills into Mobile Bay, contributing to nearly $27 billion in economic value each year. Before Hurricane Katrina, Amtrak’s Gulf Coast line traveled mostly overnight. Now, Amtrak wants to run its trains at more traveler-friendly times, clashing with peak freight hours. The rail companies insist Amtrak pay for $440 million of infrastructure upgrades, like adding passing zones or second lines of track to limit delays. Without these measures, the companies say they’re facing a “near catastrophic meltdown of freight operations.”

Their estimate exceeds that of the Southern Rail Commission, a group of governor-appointed rail proponents from Louisiana to Florida, which proposed some $60 million in upgrades after completing its report on Gulf Coast rail in 2017. What’s more, Amtrak maintains it’s not legally obligated to pay for infrastructure upgrades — especially on privately owned railroads.

If federal regulators allow freight companies to set the price of admission, it could throw a wrench in Amtrak’s growth, as well as President Biden’s climate plans. “We know we need to reduce dependency on automobiles,” said Kevin DeGood, director of infrastructure policy at the Center for American Progress. “An adverse ruling could make it substantially more expensive for Amtrak to expand their service.”

Smith said resuming passenger rail service will also improve the Gulf Coast’s ability to respond to hurricanes. He described the days surrounding Hurricane Katrina: As Mayor of Meridian and an Amtrak board member, he’d helped devise a plan to send trains to New Orleans to evacuate residents. But, according to Smith, the Mayor Ray Nagin of New Orleans declined the offer, and an 800-seat train left the city mostly empty. (Testifying before Congress, Nagin said Amtrak told the city no trains were available at the time.) Still, Smith said that shows “any route coming out of cities along the Gulf that are threatened can serve as a lifeline to move people out.”

In January 2021, following a year of negotiations, Amtrak said it had ceased bargaining with CSX and Norfolk Southern, after the railroad operators called for more studies on how rail service would affect traffic through Mobile’s port. In Amtrak’s view, there’d been enough studies, and it took its case to the Surface Transportation Board, the federal agency that resolves disputes in the rail industry. “Amtrak hasn’t been sitting down,” CSX spokesperson Cindy Schild said. “They’ve decided to make a case out of this.”

This marks the first time the board will settle such an argument. As a recent Congressional research report put it, “Amtrak’s network has seen little change in recent decades, so this power has been rarely exercised.” The ruling will likely serve as guidance for future clashes. In comments the U.S. Department of Transportation submitted to the board last December, representatives urged the regulators to uphold Amtrak’s right to the rails. Since the case is central to the Biden administration’s goals to expand rail, they wrote, “it is important to set a precedent in this case that vindicates the governing statute.”

The hearings began in February, stretching over several weeks, and took a break after ten days. They’ve drawn interest from elected officials in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania concerned about the consequences. “A bad decision in this case could make it impossible to bring passenger rail to Madison,” said Satya Rhodes-Conway, the mayor of Madison, Wisconsin, where the closest station is 30 miles away. “This discourages travelers from using rail and increases individual automobile use at a time when the nation and our city are working diligently to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Politicians from Louisiana and Mississippi see the return of rail as a boon to tourism in a region of beaches, casinos, and Mardi Gras, while lawmakers in Alabama tend to share the freight companies’ concerns. “I do not believe that this is the right time to voluntarily introduce dynamics that threaten to add to a serious supply chain [crisis],” said Alabama state representative Mac McCutcheon in his testimony to the Surface Transportation Board in February.

Marc Magliari, an Amtrak spokesperson who set up the Twitch livestream in Bay St. Louis, doesn’t expect the transportation board to reach a decision before the end of the month. In the meantime, Magliari promised more livestreams of “very busy” tracks to come, but declined to say where they’ll go next, in the interest of keeping railroad companies unaware of his next move. “It’s possible they could manipulate the traffic, knowing we’re there,” he said.

*Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify that the CSX spokesperson was referring to the process through which Amtrak sets up service.