This coverage is made possible through a partnership with Grist and WABE, Atlanta’s NPR station.

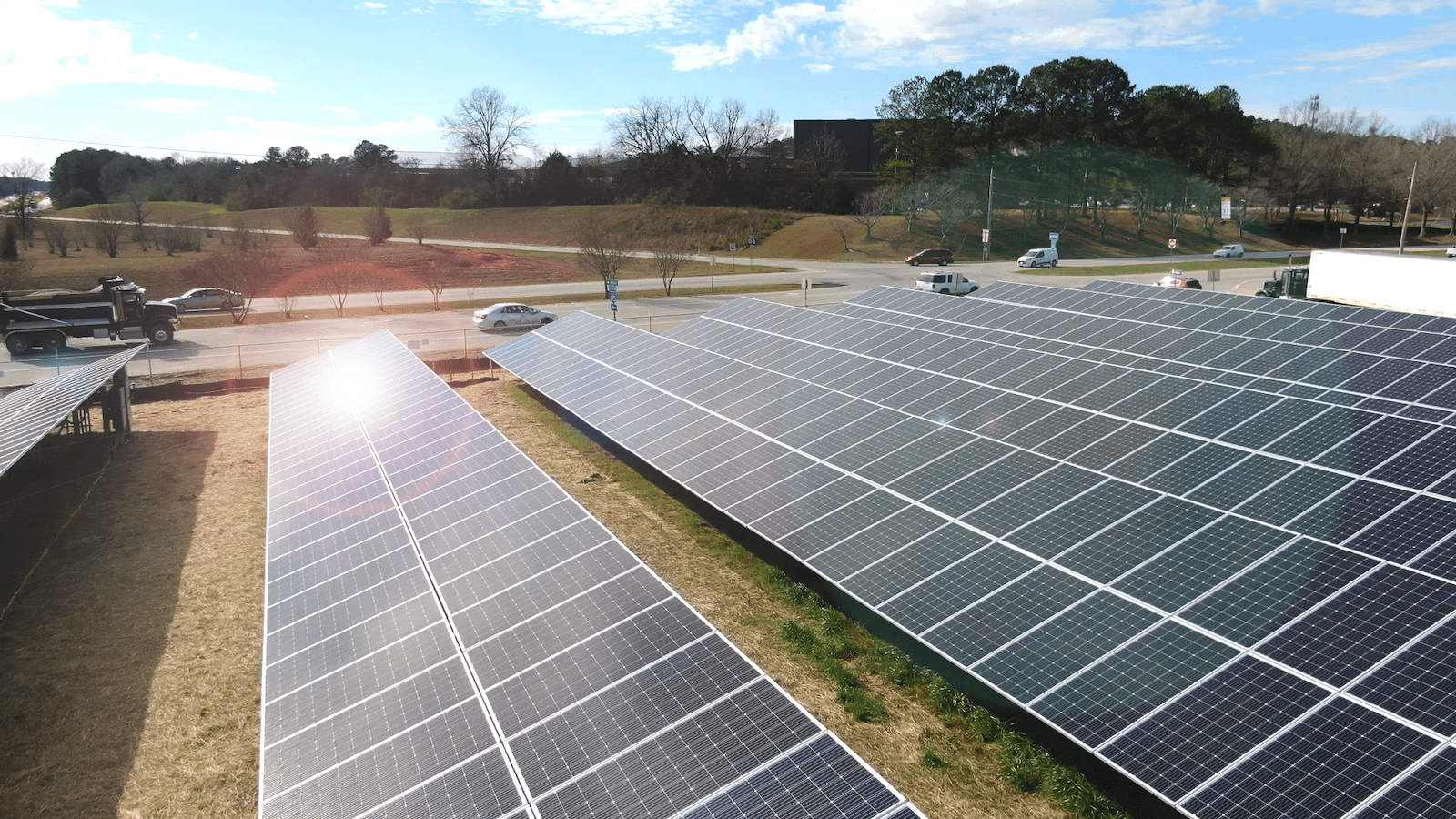

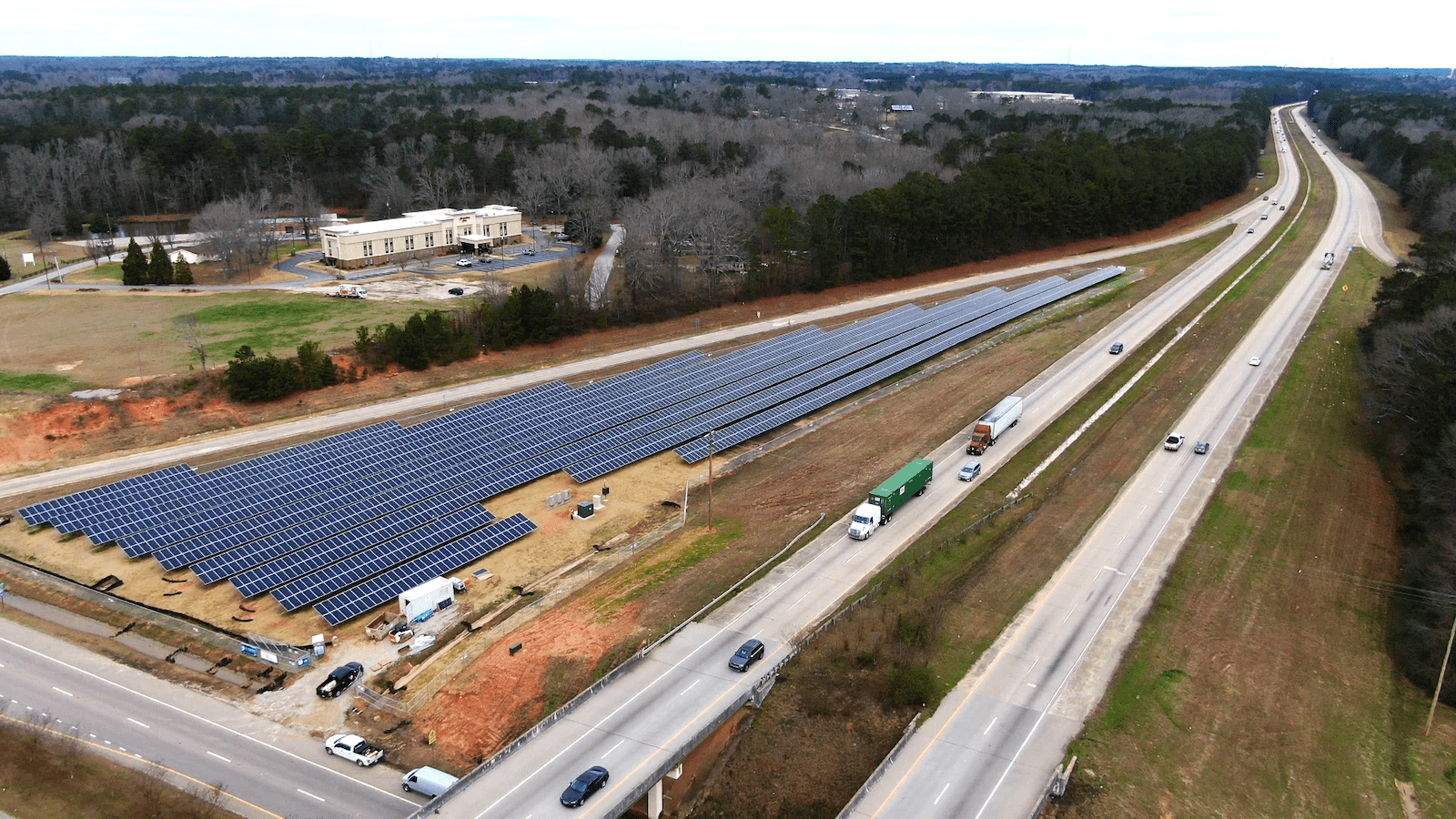

On a stretch of West Georgia highway, in the triangle of land where an exit ramp meets the road, 2,600 solar panels soak up the bright southern sun. The 5-acre site used to be barren and eroding, but now it provides enough power for more than 100 homes. That’s exactly what the team at the Ray C. Anderson Foundation’s sustainable highway project, known as The Ray, was hoping for.

“What it is today is a field of clean, green energy,” said Allie Kelly, the Ray’s executive director. The solar panels stand higher than most, so wildflowers also grow on what was once “wasted public land.”

Someday, she hopes to see solar fields like this lining highways across the country.

The Ray and mapping company ESRI, which specializes in using location data to solve local problems, have developed a free digital tool to help transportation departments realize solar projects. It finds the parcels of land where solar would work best, and planners can make a virtual mock-up to make sure the installation doesn’t block a view or sit too close to the road.

All told, the Ray estimates there are more than 52,000 acres of empty roadside land in the continental United States that could be generating solar power: in the medians, beside the shoulders, in the centers of on- and off-ramps. Placing solar panels at all these sites could generate up to 36 tera-watt hours of energy, or enough to power 12 million passenger electric vehicles, according to the organization.

As transportation departments work to reduce their emissions, many are considering solar on their unused land. Kelly said the Ray is working with more than two dozen states to help them find solar sites.

“It’s a great way for a state DOT to use underutilized land,” said Zechariah Heck, the sustainability program manager for the Oregon Department of Transportation.

Oregon installed the country’s first highway solar project in 2008, a public-private partnership that Heck said has reduced the agency’s electric bill and emissions.

But taking highway solar from an idea to reality can be daunting. Transportation departments own vast amounts of land, and not all of it can host solar panels. The land might be rocky, or filled with trees, or just facing the wrong direction. That’s where the Ray and ESRI’s digital tool comes in.

Eddie Lukemire of the Maryland Department of Transportation’s office of environment said his state has some 3,000 parcels of land along its highways.

“So when you look at 3,000 rows in an Excel spreadsheet, and then you uncross your eyes, those are just numbers,” he said. “I don’t have a column that says, are there trees on that parcel, because we don’t want to cut any trees down to put solar there.”

MDOT hasn’t formally adopted the tool, but Lukemire said it would be useful to explain and demonstrate solar projects.

“It’s really cool to be able to put that jumble of numbers into a program and have an output that is understandable by me, you, anyone,” he said.

The tool can also translate a proposed solar project into whatever terms make most sense to appeal to decision-makers, whether that’s homes powered, economic value, or carbon offsets. And it does all this work quickly.

“Delay is death for projects,” Kelly said. “We are talking about tools that carry project concepts over the valley of death, to procurement and to planning.”

Emissions reduction goals are driving some transportation departments, including those in Maryland and Oregon, to pursue solar energy.

Maryland has set a target of net-zero emissions by 2045. Highway solar stalled in Oregon after its 2008 and 2012 projects, but an executive order from the state’s governor calling for 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 reignited the program. Now, the Oregon DOT is developing new solar projects, using the Ray’s tool.

Georgia, where the Ray is based, doesn’t have climate requirements like those. And there aren’t currently plans for more roadside solar beyond the installation on the Ray.

John Hibbard of GDOT explained that most of the agency’s unused land parcels are around five to seven acres, the same size as the existing one-megawatt solar installation.

“One megawatt, which sounds like a lot, really isn’t that much,” he said. “It’s good, it’s better than zero. But it doesn’t compare with hundreds or thousands of megawatts.”

Georgia Power, the state’s largest utility, has prioritized bigger solar projects – huge fields of solar panels that can generate upwards of 100 megawatts.

But Ray founder Harriet Anderson Langford said the small solar array is part of her organization’s broader project: to showcase ways to make a road full of cars more sustainable.

“We hope what we do is inspiring to some other places,” Langford said. “That’s our goal.”