The dry, dusty rangeland of the Texas Panhandle could not have been more perfectly suited to burn. Temperatures were 25 to 30 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. The air was dry, with humidity below 20 percent. And wind speeds were as high as 60 mph. Those hot and dry weather conditions worried meteorologists in the region, and their worst fears were realized February 26 when a spark set off a massive fire.

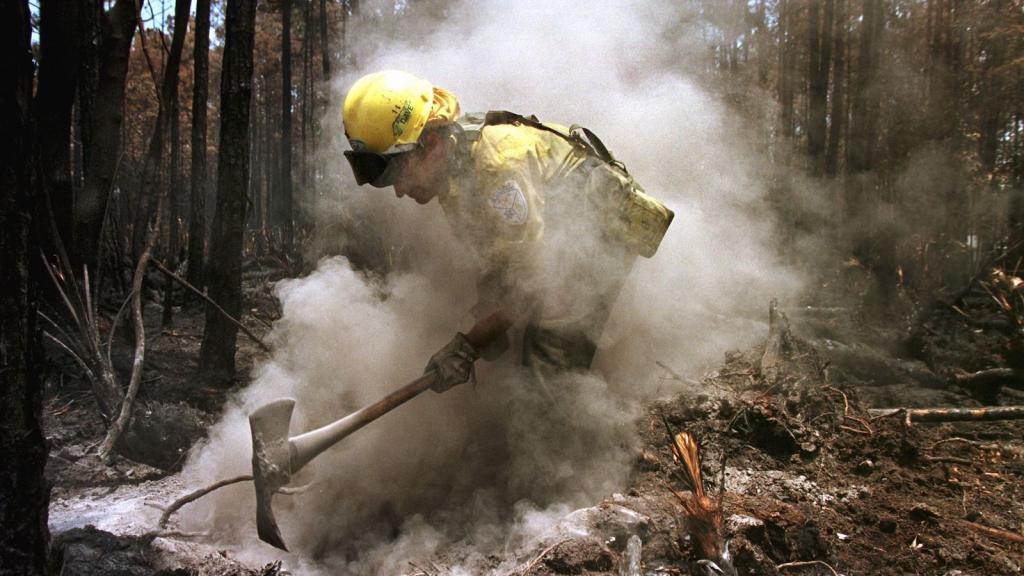

Over the past 10 days, five wildfires in the region have burned more than 1.2 million acres. The largest of them — dubbed the Smokehouse Creek Fire, for a creek near its origin — stretches across an area larger than Rhode Island. It’s the largest and most destructive wildfire in state history. Entire communities have had to evacuate. Two people have died. After more than a week of constant effort, crews have contained just 44 percent of the Smokehouse fire.

The fire has destroyed more than 500 homes, and thousands of cattle, horses, and goats have either succumbed to the fires or been euthanized. In light of the devastation, Governor Greg Abbott declared a state of emergency for 60 counties and requested additional resources from the federal government to battle the infernos.

“As Texas experiences the largest wildfire in the history of our state, we remain ready to deploy every available resource,” Abbott said at a press conference earlier this week. “The wildfires are not over yet, and until they are, it is essential that Texans in at-risk areas remain weather-aware to maintain the safety of themselves and their property.”

It remains unclear exactly what caused the spark, something officials with the Texas A&M Forest Service continue investigating. Landowners suspect a downed power line may be to blame — an increasingly common cause of wildfires. In California, six of the state’s 20 largest fires started that way.

Texas firefighters routinely handle large fires. On average, wildfires scorch roughly 650,000 acres each year. In 2011, amid a prolonged and severe drought, Texas experienced one of its worst fire seasons in history, losing nearly 4 million acres. The Panhandle was particularly hard hit. Nationwide, researchers have found that wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense, with the season essentially running year-round.

While the severity of wildfires depends on geography and vegetation, weather plays a key role in their frequency and how difficult they are to contain. These immense blazes require hot and dry conditions, and a warming planet has been making those conditions more common. The high plains of Texas now experience 32 more days with hot, dry, and windy weather conditions than in the 1970s, according to an analysis by Climate Central, a nonprofit tracking climate effects.

“You’re seeing more days when temperatures are high, and you’re seeing more days when it is hot, dry, and windy all at once,” said Kaitlyn Trudeau, a senior research associate there. “It’s a threat multiplier.”

Climate change is also making wildfire solutions harder to implement. Prescribed burns, in which fire officials start a controlled fire to clear overgrown brush and scrub, are a controversial but effective tool to manage the amount of vegetation that can feed a fire. Weather is a key determinant of when to conduct them. If conditions are too hot, dry, and windy, these relatively small fires can get out of control. A warming world is making the cooler, more humid conditions that prevent runaway fires harder to come by. That was the case in New Mexico last year when federal officials began a prescribed burn in the Santa Fe National Forest only to lose control. More than 341,000 acres burned. Officials had underestimated just how dry conditions were.

Fighting wildfires has become harder, too. Typically, cooler nighttime temperatures offered crews a reprieve. But as the planet warms, nighttime temperatures have been rising more quickly than daytime temperatures. A 2022 Climate Central analysis found that on average summer nights were 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer in 2022 than in 1970. That means blazes can continue to pick up speed after sunset, challenging firefighters through the night.

“Climate change is not only making fires worse and more dangerous, but it’s also reducing our capacity to address the problem,” said Trudeau.