We’ll be reporting all day on the U.S. climate change impacts report released by the White House and a team of 13 federal agencies today. We’re also tracking good coverage of the report elsewhere—check back for updates, post your own in the comments below, or post them to Twitter with @grist in the text.

UPDATE: More localization from the Texas Energy and Environment blog of the Dallas Morning News:

The report says much of the Texas coastline will be awash and that North Texas’ generally hot, dry summers will be hotter and drier. How much so depends on whether anthropogenic (people-made) greenhouse gas emissions come under control a little, a lot, or not at all.

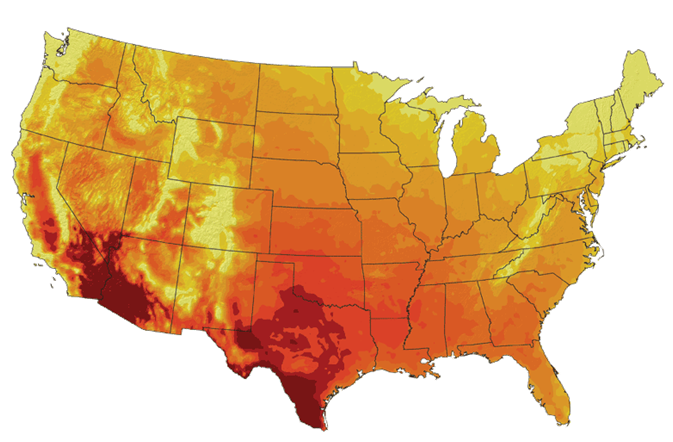

Texas is in the climatological and economic crosshairs in any climate change scenario. Maps of projected climate impacts in the report tend to be darker and more serious across North and Central Texas and the far southwest.

If correct, that means health risks, habitat and agricultural shifts, and changes in water availability — more frequent droughts from about Dallas westward. And of course a low-profile coast is what it is, which is wet, storm-prone and vulnerable.

And there’s Texas’ special relationship with greenhouse gases, which is that it makes money doing things that emit them, such as providing a big slice of the nation’s oil, gas and chemicals. Throw in cars, trucks and fossil-fuel power plants and it’s clear how much Texas has at stake.

UPDATE: From St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s ecospeak blog:

The study has a particularly unsettling look about the future temperature for Illinois. Basically it shows the state’s climate will look more like Arkansas’ in 30 years and resemble Texas by the end of the century.

UPDATE: Jeff Kart of Michigan’s Bay City Times localizes the story to the Great Lakes by interviewing Kim Hall, a climate change ecologist with The Nature Conservancy in Lansing.

What are the projections for Michigan and the Great Lakes?

“We should obviously have warmer temperatures and increased rainfall, especially in the spring and summer,” Hall said.

“Those two are kind of related in that the warmer the air gets, the more water the atmosphere can hold … Storm events are likely to be a lot more intense because the air temperature allows those storms to hold more rain, which then comes plummeting down.”

For anyone familiar with the Saginaw Bay watershed, that could translate to more sewer overflows.

“No one wants to hang out (at the beach) with the E. coli,” Hall quipped.

“All of our infrastructure was built under a different assumption regarding storm events. We really need to adjust our assumptions to think about much larger storm events and build infrastructure that can handle that.

And:

“This report suggests all of the Great Lakes are going to drop between 1 and 3 feet” by 2080, she said.

That means more exposed shoreline and the potential for more phragmites and other invasives.

UPDATE: The Washington Post leads with the “it’s already here” message:

Man-made climate change is already lifting temperatures, increasing rainfall, and raising sea levels around the United States — and its effects are on track to get much worse in the coming century, according to a report released this afternoon by federal scientists.

The report, “Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States,” covers much of the same ground as previous analyses from U.S. and United Nations science panels. It finds that greenhouse-gas emissions are “primarily” responsible for global warming and that rapid action is needed to avert catastrophic shifts in water, heat and natural life.

What’s different this time is the report’s scope — at 196 pages, the report attempts to present the fullest picture yet of the threats to the United States — and its timing.

Suzanne Goldenberg of the Guardian offers political context:

Today’s release is part of a carefully crafted strategy by the White House to help build public support for Obama’s agenda and boost the prospects of a climate change bill now making its way through Congress.

For many Americans, the report released today, entitled Global climate change impacts in the United States provides the most tangible evidence of the economic costs of climate change – from the need to relocate airports in Alaska built on permafrost, to the increased need for pesticides in agriculture, to an electrical grid straining to meet the increased demand for air conditioning in summer and ageing sewer systems brought to bursting point by heavy run-off in 770 American cities and towns.

And this:

Today’s release of the report was part of a methodically planned media roll-out by the Obama administration.

Scientists who have seen the report said the administration spent several weeks honing the language and graphics to make it accessible to non-scientists and to sharpen its core message: America must act now on climate change.

As part of the PR surrounding the release of the report, the administration approached the San Francisco consulting firm, Resource Media, which specialises in environmental campaigning, to oversee the release, and produce a shorter and more digestible brochure of today’s report for wider public distribution.

The New York Times alludes to the “bathtub effect”—even if we turn off the faucet of greenhouse gas emissions, the level already in the tub remains a problem:

Even if the nation takes significant steps to slow emissions of heat-trapping gases, the impact of global warming is expected to become more severe in coming years, the report says, affecting farms and forests, coastlines and floodplains, water and energy supplies, transportation and human health.

And Reuters led off with an overview yesterday:

While the report was not available Monday, it is expected to be similar to a draft version posted online in January.

Among the January draft’s key findings:

— climate change is already affecting water, energy, transportation, agriculture, ecosystems and health, differing from region to region and expected to grow if the climate changes as projected;

— agriculture is one sector most able to adapt to climate change, but increased temperature, pests, diseases and weather extremes will challenge crops and livestock production;

— threats to human health will increase, especially those related to heat stress, water-borne diseases, reduced air quality, extreme weather events and diseases transmitted by insects and rodents;

— sea-level rise and storm surge place many U.S. coastal regions at increasing risk of erosion and flooding, especially along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, Pacific islands and parts of Alaska; energy and transportation infrastructure in coastal cities is very likely to be adversely affected.