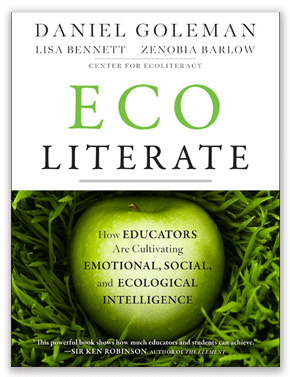

In the new book Ecoliterate, authors Daniel Goleman, Lisa Bennett, and Zenobia Barlow argue that integrating emotional, social, and ecological intelligence leads to more effective environmental education and more effective activism. Here’s an excerpt from the book about one inspiring activist.

Teri Blanton. (Photo by iLoveMountains.org.)

Teri Blanton grew up on a dirt road in Harlan County, Ky. The daughter of one coal miner and sister of another who died in a mining accident, Blanton left briefly to marry, and then returned at 25 as a single mother of two. She bought a few acres of land behind her parents’ house and settled into a mobile home with her children and two big dogs. For years, she didn’t think twice about coal — until her kids, who waited for the school bus on the same road traveled by coal trucks, started complaining.

“You know, my son would say, ‘Our shoes get dirty before we get to school,’” Blanton recalls. “And, one morning, he told me, ‘Somebody has to drive us across this part of the road every day, because the coal muck is there.’ I went down there, and I’d seen it,” she says, “and it was just disgusting.”

Blanton called the county highway department to ask that they clean up the sludge, even by simply digging a ditch so it would run off to the side of the road rather than pool near the school bus stop. Instead, a coal truck appeared outside her mobile home and circled it all day.

“I called the road department dude back,” she recalls, “and said, ‘By any chance, did you call the mining company?’”

When he said yes, she asked to speak to his supervisor, whose only response was, “Lady, you have to learn to live with this if you live in a coal mining town.”

“I beg to differ,” she said. “My kids aren’t wading through muck to get on the school bus.”

Then she told the mining company that if they thought sending a coal truck to circle her home all day would intimidate her, they had another thing coming. “I don’t know why I felt so fearless,” she notes. “I probably should have been afraid, you know, but I wasn’t.”

Blanton eventually convinced the highway department to build a new road. But then her children began breaking out in rashes after taking baths, and she discovered that the groundwater feeding her well was poisoned with toxic chemicals from a nearby coal plant. She joined forces with two other women to educate her community and asked state and federal authorities to test their water. The women were portrayed as hysterical housewives in the local newspaper, she recalls. But they succeeded in getting the water tested, which led to the EPA declaring their community a Superfund site.

Some 5,000 pounds of contaminated soil were excavated (and trucked to Alabama to be stored next to a poor African-American community). But before the government took the next step — of extracting the contaminated groundwater through a pump-and-treat system — Blanton decided she’d had enough.

“In my mind, I knew that they were going to poison me and my kids all over again,” recalls Blanton, a cancer survivor. So she loaded her mobile home onto a flatbed truck and moved it, her children, and her dogs to western Kentucky. Leaving Harlan County, however, did not mean leaving behind her commitment to address mountaintop mining. She had come to understand all too well its impact on the people, land, and water. And she felt too much empathy for the people of her hometown — many of whom had died in their 50s and 60s.

Blanton has dedicated her life to fighting mountaintop mining ever since — standing up to coal companies; becoming a leader in Kentuckians for the Commonwealth; lobbying in Washington, D.C.; speaking to thousands of people at rallies; being arrested; and challenging her state senator on MSNBC.

In the process, she developed an instinctive sense of emotional, social, and ecological intelligence — enabling her to effectively educate and inspire others about environmental issues. Among her most essential lessons learned, she says, are these:

- Don’t communicate from a place of anger. “I started out expressing anger. I was angry. But that was not going to reach anybody.” You must be aware of your own feelings, have the ability to control them, and develop the facility to interact effectively with others.

- Reach people on the human level through stories. “I could tell you one statistic after another. But that isn’t going to reach you.” Effective leaders have empathy toward others and make connections for people by focusing on the human impact.

- Foster dialogue instead of debate. “I always try to find a place in conversation where you and I agree on something. And once we agree on something, then we can go on to have a dialogue.”

- Speak from the heart. Blanton learned this from a friend, Patty Wallace, who told her at a rally years before, “Put down the damn speech …”

Make ecological connections clear to others. Blanton and her friends have been known to sing to make their point about the consequences of mountaintop-removal coal mining: “If you blow up the mountains, Push it in the valley, You gonna reap just what you sow.”

Make ecological connections clear to others. Blanton and her friends have been known to sing to make their point about the consequences of mountaintop-removal coal mining: “If you blow up the mountains, Push it in the valley, You gonna reap just what you sow.”

Adapted with permission of the publisher, Jossey-Bass, a Wiley imprint, from Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence, by Daniel Goleman, Lisa Bennett, and Zenobia Barlow. Copyright © 2012 by the Center for Ecoliteracy.