HOV-3 lanes allow cars with at least three people a fast route to the city.

It’s a Wednesday morning like any other, and Vicky Manalansan is speeding down the freeway toward Washington, D.C., in her silver minivan. Riding in her backseat are two complete strangers she picked up at a suburban commuter lot.

Smartphone-wielding techsters in San Francisco might call this “ridesharing,” but in the D.C. area, where carpooling has been an accepted way of life for decades, they call it “slugging.” Each day, an estimated 10,000 commuters in northern Virginia hitch rides this way. Passengers get a free ride; drivers get a free pass to use the special “HOV-3” routes, open only to cars holding three passengers or more.

“With the price of gas, and this traffic here,” Manalansan says, gesturing to the jammed lanes of 395, “it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me.” During the almost two decades she’s been doing this, she says, slugging has reduced her commuting time by more than half.

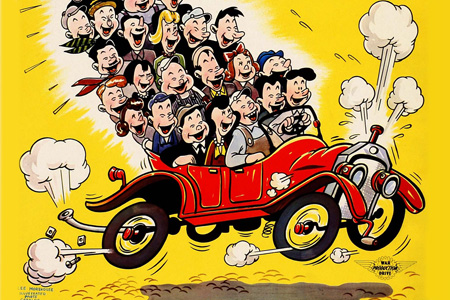

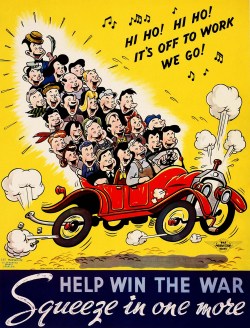

Carpooling is nothing new. In the United States, it began during World War II as a money- and resource-saving device. Likewise, sharing cars with strangers predates all those ridesharing apps by decades. Northern Virginia’s dedicated HOV-3 lanes along 395 were constructed in 1969, and commuters have picked up strangers ever since.

Slugs were so named by bus drivers trying to distinguish between carpoolers and people standing in line for the bus, much as they once kept a vigilant eye out for fake bus tokens — known as “slugs.” There are also slugging systems in San Francisco, Houston, and Pittsburgh. And, internationally, Jakarta has HOV-3 lanes to help with its intense traffic, though that system is not without flaws.

But slugging was born in the nation’s capital, and it continues to thrive here. The D.C. area has the second-busiest traffic during rush hour in North America, according to a November 2010 report by NAVTEQ. To avoid the congestion, approximately 13 percent of D.C.-area commuters carpool in some fashion. The number is even higher — 18 percent — in Virginia’s Fairfax County, where slugging began.

Those HOV-3 lanes are key. Slugging doesn’t work with HOV-2 lanes, open to cars with just two people, that allow drivers to merge with other traffic. First, riders and drivers alike feel safer with three people in the car instead of two, so people are more likely to carpool with the HOV-3 system. Second, having clear entry and exit points to the HOV-3 lanes helps the police enforce the three-person requirement and prevents other drivers from cutting in and out of the HOV lane; barring an accident, the lane always makes for a much faster trip into the city. The HOV-3 system also helps establish a handful of popular pick-up and drop-off points along the route.

Having a transit system in place is crucial to slugging’s success — if no drivers show up, riders need to have an alternative, like taking the bus. That’s why slug lines often form around bus stops.

There are some small rules of etiquette for slugs: Don’t yak on your cell phone, don’t ask the driver to change the radio station, don’t try to chat with the driver the whole time — in general, don’t bug the driver. But for the most part, slugging is easy to pick up.

And it seems to work. In nearly two decades, Manalansan has never had a negative experience. “I see them all the time,” she says. “I don’t know their names, but I see their faces.” She gets to know the slugs who stand in the same line day after day, and they are professional and polite without fail. These are, after all, her neighbors.

And it seems to work. In nearly two decades, Manalansan has never had a negative experience. “I see them all the time,” she says. “I don’t know their names, but I see their faces.” She gets to know the slugs who stand in the same line day after day, and they are professional and polite without fail. These are, after all, her neighbors.

In fact, picking up slugs has been a boon for Manalansan’s business — she runs a flower shop in D.C. “It started with one person, 18 years ago,” she says. “She introduced me to everyone in the office at the World Bank.” Now Manalansan does brisk business with the bank, and she keeps business cards in the ashtray of her minivan. “You never know the referrals,” she says.

Such positive stories abound in sluglore: Carolina Marin found her son’s nanny through a regular slug. Another slug found her mechanic through a driver.

In fact, there has been only one reported incident with slugging. Gene C. McKinney, once the sergeant major of the U.S. Army, picked up slugs near his home in Manassas, Va., in October 2010. The passengers asked to be let off near Pentagon City after McKinney drove fast and erratically. When one of the slugs tried to snap a photograph of the driver’s license plate, McKinney hit the gas and the man. The former top soldier served a short jail sentence after he pleaded guilty to attempted malicious wounding.

Virginia law bans people from soliciting rides from the side of roads, but when it comes to slugging, the state looks the other way. Joan Morris, spokesperson for the Virginia Department of Transportation, says that slugging was “created by commuters for commuters.” “It’s been very successful,” she says, “and we stay out of it.” VDOT can’t actively encourage people to ride with strangers because of liability issues, Morris says, but officials take slug lines into account when they are building commuter lots.

The practice has been such a success that transportation officials have expressed interest in bringing it to cities in Colorado, Washington, Maryland, New York, and Illinois, says David LeBlanc, a retired Army officer who founded the only website devoted to slugging, Slug-Lines.com, and wrote the book Slugging: The Commuting Alternative for Washington DC. There is also talk of adding HOV-3 lanes along the I-95 corridor, which would encourage ridesharing.

“Initially, it was a kind of adversarial relationship between slugging and any transportation office or official,” LeBlanc says. “Now it’s a much better working relationship. People are wondering, ‘Hey, what can we do to make this better for all of us?’”

Frank Lakwijk, a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, has been picking up slugs in Springfield, Va., for 10 years. He’s surprised by how few of his coworkers know about or understand slugging. “They think it’s hitchhiking. But I would never do that,” he says emphatically. “This is organized, polite; it doesn’t feel risky at all. People don’t pay attention to gender. It just works.”

No app required.