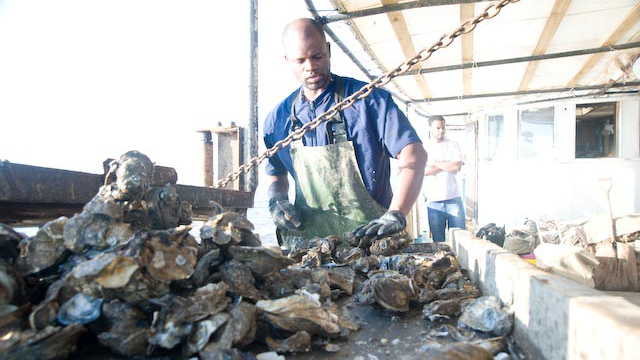

Shawn EscofferyOystermen of Plaquemines Parish, La.

Whether you live in Seattle, Baltimore, or Schenectady, N.Y., if you’ve had an oyster dish, chances are the shelled delicacies came from the Gulf of Mexico, most likely off the Louisiana coast, which produces a third of the nation’s oysters. Crabs? Hate to break it to you, but those luscious “Baltimore” crab cakes — yep, those are from Louisiana too.

This has been a fact for a long time, but it might soon become an artifact. The reason: the BP oil spill disaster of 2010, which dumped over 205 million gallons of oil and another 2 million gallons of possibly toxic dispersants into the Gulf, devastating the area that’s responsible for 40 percent of the seafood sold commercially across the U.S. For the end user, this just means Maryland chefs actually using Maryland crabs again. But on the supply side, this means that whole communities of fishers along the Gulf Coast have been put out of business, their livelihoods ruined.

Oystermen have fared among the worst in that bunch, notably the African-American oystermen who live and work in Plaquemines Parish, on the lowest end tip of Louisiana. They used to harvest a great deal of the shellfish that eventually adorned our restaurant plates, but the impacts of the BP disaster have proven too difficult to rebound from. They’re now facing “zero population” of oysters, as one seafood distributor put it.

For too long, these black oystermen have been invisible not only to the nation they serve but also to the state they live in. The new documentary Vanishing Pearls from first-time filmmaker Nailah Jefferson hopes to raise the oystermen’s visibility and also our awareness of their value in our national economy and environment.

Nailah Jefferson

Jefferson, a New Orleans resident, began making the film shortly after the BP disaster, based off a friend’s tip. She followed that tip down to Pointe à la Hache, on the east bank of the Mississippi River, where a small community of black fishers live and have subsisted off the bays there for decades. (You can read more about them in this story I reported shortly after the spill.) After meeting them, Jefferson immediately concluded that the hardscrabble men and women here deserved more shine, especially in the face of a disaster that threatens to destabilize their lives with little remedy.

Vanishing Pearls makes its national debut on April 18 in New York and Los Angeles. It’s the culmination of more than three years of work by Jefferson, filming and reporting on the BP disaster’s impacts long after the rest of the media shifted their focus elsewhere. The documentary was featured this January at Slamdance, the Utah-based film festival known for showcasing breakout films that Sundance slept on. Christopher Nolan and Lena Dunham are among the directors discovered at Slamdance.

Slamdance also helped Jefferson catch the attention of Ava DuVernay, founder of the pioneering film distribution company African-American Film Festival Releasing Movement (AFFRM), and the first African-American woman to win the Sundance Best Director prize for her 2012 film Middle of Nowhere. With DuVernay’s power behind the project, Vanishing Pearls will now throw more shine on the struggling black oystermen than Jefferson originally imagined. Friday’s opening coincides with the four-year commemoration of the BP disaster.

I was able to catch Jefferson by phone from her home office in New Orleans to discuss her filmmaking experience and the fate of these oystermen.

Q. So how does it happen that entire communities are just rendered invisible?

A. Because they don’t matter enough. It’s about the money. Down there in Pointe à la Hache, you have a fishing community that has contributed so much to our state, our identity, and our economy. But what contributes more is oil and gas, and fishing has historically been in the way of the growth of oil and gas. So when up against the industry, they don’t matter. [The oystermen] know that, that the terms are unbalanced in favor of the oil and gas industry, but I don’t think they thought that a natural disaster would come and wipe out entire portions of their livelihood also. We will continue to drill, because it’s just a way of life here, but I think the state needs to work harder to strengthen regulations so that if another disaster occurs, it won’t wipe out the remaining estuaries that are still thriving.

Q. While your film is about people and communities, you didn’t shy away from breaking down the environmental toll of the BP disaster. Did you personally have much background in the science?

A. No, it was a steep learning curve. I interviewed Dr. Ed Cake, who’s one of three well-known oyster biologists in the Gulf Coast, because this is absolutely not my field. But I felt that if this was a story I was going to tell, I’d better dive in and figure it out. I didn’t want to bog people down with the science, but if you don’t grasp even a little bit of it, then you won’t get the whole story.

Q. You show that the oyster beds were exposed to some oil and dispersants. How do you deal then with the question of whether seafood is safe to eat?

A. The best way I can describe it is the way Dr. Cake explained it to me: Oysters are like the canaries in the coal mine. If they’re able to survive, thrive, and reproduce, then the waters are OK; if they’re not, then the waters are unhealthy. At the time that the spill had occurred, the dispersants had been sprayed, but the full effects hadn’t played out yet. So there were still oysters that could be harvested in that area. The last of that harvest came in late 2011. The Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Department put a hold on fishing, closing the public [oyster bed] grounds for a long time, and then when they opened them back up, those guys went out and harvested the last of what survived. There hasn’t been much left.

Q. The oystermen come across as the real scientists in your film.

A. I think when people think of fishermen, they think of simple bayou people who aren’t educated. Perhaps they haven’t been in school for the longest time, or they don’t have post-grad degrees, but they are very much knowledgeable about what they do, and it’s something they’ve done for years. I wanted to show that their work is more complicated and harder than people think. You have to have a certain type of intellect to get this work and be successful at it.

Q. You find many of the oystermen in the film talking about generational instructions on how to harvest oysters sustainably. Did you get the sense they were natural environmentalists?

A. Yes, it was clear from when I first met them that these are the real environmentalists, because they actually have to live off the land and water. It really is in and of itself a science that’s been passed down to them, and I think it’s their passion for this work that makes them want to remain bayou residents.

Q. Despite their expertise, they’ve had to play defensive with scientists and environmentalists, notably those who under the Louisiana coastal master plan want to use freshwater diversions to replenish the eroded marshlands, even though this will ruin what’s left of the oyster beds. Did you sense that professional environmentalists respected these fishers’ expertise at all?

A. There isn’t proof that these freshwater diversions will work or will be as beneficial as stated. People have told them, “Look, you’re going to have to sacrifice for the greater good of the state.” If the diversions were something proven to work, then it probably wouldn’t be such a harsh pill to swallow for them. It’s not that the [environmentalists] know better [than the oystermen], they just understand things differently. We need a more collective approach moving forward.

Q. What can people do after seeing your film if they want to help?

A. One reason I signed with AFFRM is that they are very supportive of social advocacy campaigns. We’ve already launched one and hope to do more around supporting efforts to clean up the spill and make sure regulations are tighter so that we don’t have this kind of occurrence again. We have a petition you can sign encouraging EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers to support efforts to tighten regulations under the Clean Water Act so that our streams and tributaries going into the Mississippi River won’t be polluted — and also, of course, so those communities who rely on those waters will be able to have healthy water again.

—–

Watch the trailer for Vanishing Pearls: