The Exxon Valdez, at the still-young age of 26, will soon leave this world once and for all.

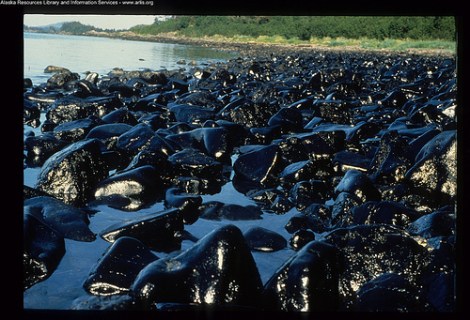

Rocks covered with oil from the Valdez. (Photo courtesy of ARLIS Reference.)

Yes, the ship that in 1989 drenched the beaches of Alaska in crude oil is still around, having fled the scene of its crime to drift through Europe under an assumed name, like so many disgraced scoundrels before it. With Oriental Nicety now written on its outermost layer of paint, the ship sits off the coast of India, having only recently learned its fate from an Indian court: death.

From Nature:

[I]n 2011, … she was sold for $16 million to an Indian demolition company, Priya Blue Industries. The same company had attracted bad press in 2006 for breaking down a ship called the Blue Lady, despite knowing that she contained asbestos. Activists claimed that the Oriental Nicety, too, was contaminated with asbestos and polychlorinated biphenyls, a persistent organic pollutant. The Indian Supreme Court forbade docking of the ship and imposed an environmental audit.

So the Oriental Nicety sat on death row for two months, costing her owner $10 million as the value of its steel declined and the company continued to pay its crew.

Last month, the court ruled in favour of Priya Blue: there was no toxic waste on the ship. The Oriental Nicety is welcome to beach at Alang, the world’s largest ship-breaking yard, where she will be dismantled for scrap.

Rest assured, the Valdez will no doubt do its share of polluting on its way into Exxon Valhalla. This is the shipyard at Alang.

[protected-iframe id=”c196da4c1ea84053a10ea9fe49e44f31-5104299-36375464″ info=”https://maps.google.com/maps?hl=en&ie=UTF8&t=h&ll=21.423738,72.212598&spn=0.002996,0.002516&z=18&output=embed” width=”470″ height=”600″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no”]

Zoom out, scroll up and down. It’s a massive ship-breaking operation, in which hundreds of people set to work tearing down vessels as quickly and completely as possible. In 2000, The Atlantic wrote about the Alang dismantling operation.

Alang, in daylight barely recognizable as a beach, a narrow, smoke-choked industrial zone six miles long, where nearly 200 ships stood side by side in progressive stages of dissection, yawning open to expose their cavernous holds, spilling their black innards onto the tidal flats, and submitting to the hands of 40,000 impoverished Indian workers. …

Alang is a wonder of the world. It may be a necessity, too. When ships grow old and expensive to run, after about twenty-five years of use, their owners do not pay to dispose of them but, rather, the opposite — they sell them on the international scrap market, where a typical vessel … may bring a million dollars for the weight of its steel. Selling old ships for scrap is considered to be a basic financial requirement by the shipping industry — a business that has long suffered from small profits and cutthroat competition. No one denies that what happens afterward is a dangerous and polluting process.

It’s a fascinating (and very long) read, and conveys just how fitting an end we are giving to an inanimate vessel that became an unwitting symbol for human error. Error in the form of a ship’s captain who’d had too much to drink; error in the form of a ship with one hull carrying toxic material in rough water; the error of our need for oil in Alaska — this last an error we’re fully prepared to repeat.

The Valdez was just a concept, a collection of pieces of steel that failed in a way that shifted how people looked at the world. In a few months, at the hands of several hundred poor men on the coast of India, it will be pieces of steel once again, and the Valdez will become a pure, negative abstraction.