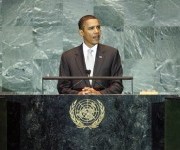

“There is no time to waste. America has made our choice. We have charted our course, we have made our commitments, and we will do what we say.” — President Obama, speaking to world leaders in Copenhagen December 18

“Kan Han?” (Can He?) So implored the headline and full-page picture of President Obama on the front of the Copenhagen MetroXpress on December 18, the day the President flew in to rescue the climate summit.

With negotiations on the verge of collapse, Obama narrowly averted a total disaster with a strong show of determination and some deft eleventh-hour negotiating. The talks failed to produce a formal and comprehensive commitment to climate solutions, but they did deliver some important pieces of the puzzle. Top-level engagement from the world’s two largest emitters, the U.S. and China, is new and essential. And negotiators took a real step forward on financing adaptation and clean development in the global South, the moral and practical imperative at the heart of any fair global deal.

President Obama was dealt a weak hand by the Senate’s failure to adopt comprehensive climate and energy legislation before the negotiations. Other factors contributed, but the Senate’s punt set the stage for the tepid result in Copenhagen. The world will not move forward decisively until the U.S. is in with both feet – and both houses of Congress.

Understanding the U.S.’s pivotal role, Obama leaned forward and made a definitive-sounding pledge: “We have made our commitments, and we will do what we say.” But he can’t make it stick until Congress finishes its work. The window is short: scientific, diplomatic, and political imperatives demand immediate action.

The President is clearly engaged — a huge step one on America’s road to recovering its credibility in the international process, after having walked away from Kyoto. Six of his cabinet Secretaries came to the summit and impressed the world with their focus and administrative actions to date. But the inconvenient truth about our weak standing in the negotiations remains naked: The nation that has contributed the most to global warming still has no national climate policy.

I went to Copenhagen in part to demonstrate the breadth of action and commitment to climate solutions in the U.S., especially at the state and local level. But international colleagues and delegates cross-examined me about our broken legislative process, and why it has been so slow to deliver. I have a lot of theories, but no remotely adequate excuse. The U.S. must step up — and in a stark, defiant, powerful sentence, the President promised we would: “We will do what we say.”

To be clear, “what we say” — the emission reduction target the President put on the table — is not nearly enough to do our part in staving off catastrophic climate disruption. It’s far less than other developed nations have pledged. We will need to do much more. But it was the effective constraint that Congress imposed and the President accepted on the U.S.’s ambition in Copenhagen.

So the immediate question is, “How?” How will the President make good on his commitment? Will he rely on existing executive authority? Partly. EPA Secretary Lisa Jackson was in Copenhagen a day after the agency’s landmark “Endangerment finding” to affirm that the Administration will use the Clean Air Act to reduce climate pollution. But Jackson and the President have also made it clear they don’t think current executive authority is enough. And they’re right.

We know what the problem is: the Senate’s paralysis — a symptom of the polarized, dysfunctional politics that has turned this urgent global imperative into a political football in Washington. The only really meaningful test of whether “we will do what we say” is whether the Senate gets cracking on it immediately after health care. But they won’t do it unless the President leads the charge with a lot more gusto.

Senate leadership is afraid of this issue. They’re afraid of losing seats in the midterms. They’re afraid that opponents will successfully frame the climate and energy policy as a job killer. They’re afraid of another bruising political battle after health care.

This is where FDR (and some WWII-like urgency) would come in handy: fear itself is what’s killing them. While they cower, they are squandering the opportunity to frame this as what it really is: the most effective, politically galvanizing strategy for job creation and economic renewal available to them. Opponents of climate policy are rushing to fill the void with all manner of lies about climate science and energy economics. The nay-sayers’ arguments are weak, but their resolve is firm. The opposite is true of the proponents (if we can even really call them that yet).

A short term jobs package won’t deliver a fraction of the economic punch that a real climate and energy policy packs. A cap on carbon emissions will yield a lot more “cash for caulkers” than a one-time, near-term public outlay. Instead of pushing a jobs bill out ahead of the climate and energy bill, Congress should do them together. The climate and energy package – with short-term job stimulators and long-term job drivers – can be the main engine of economic and political recovery. The President has argued for a systematic transition to a clean energy economy repeatedly and eloquently, but he hasn’t broken through yet. Pushing jobs, energy, and climate together instead of sequentially would make his case much more persuasive.

Americans know that fossil fuel dependence is a dead end street, and they’re ready for leaders to get real about what it takes to turn onto a clean energy path. The President has demonstrated the winning politics of this: Democratic and Republican rivals offered campaign lollipops last summer — gas tax holidays and drilling binges – while candidate Obama called for a bold energy transformation. He won.

It is certainly possible to lose this fight. The best way to lose it is to recoil from having it — the strategy Senate leaders and Democratic political operatives seem to be pursuing now. This only emboldens opponents and demoralizes supporters.

The President ran on this issue. He believes in it. He understands its transformative economic power and the moral imperative to tackle it. He mined the rich political ore of our frustration with Washington’s chronic failure to address our fossil fuel addiction. The question now is whether he will forge that raw material into the steely resolve he’ll need to get an effective climate and energy bill done.

Losing this fight because he won’t have it would undermine the President. He was elected in part because he picked it. Now he needs to have it and win.