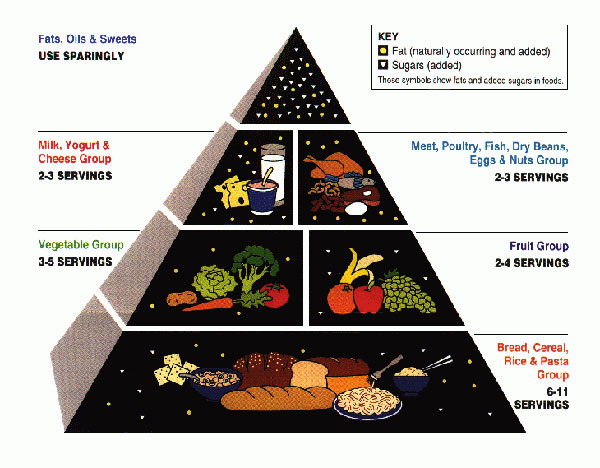

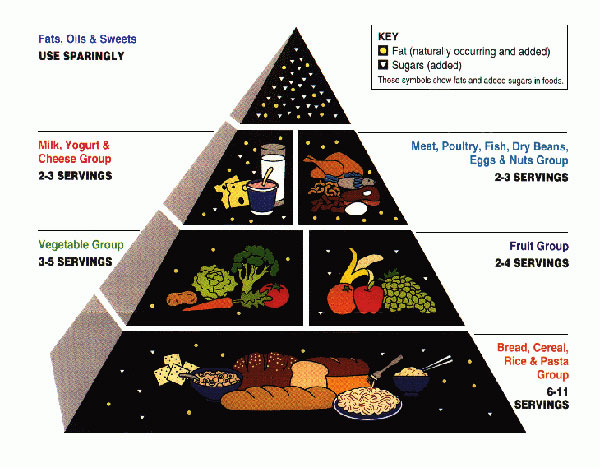

The USDA’s current food pyramid, showing the servings from food groups recommended daily. Image: USDAReporter Jane Black has a good overview of the upcoming revision of USDA dietary guidelines in today’s Washington Post. As she observes, Big Ag and Big Food typically resist any attempts by the government to give specific advice on which foods and how much of them you should eat. Black leaves it to nutritionist Marion Nestle — who wrote a book about her own experiences drafting a revision to the dietary guidelines in the 1980s — to sum the whole problem up: “The only time they talk about food is if it’s an ‘eat more’ message … If it’s a question of eating less, then they talk about nutrients.”

The USDA’s current food pyramid, showing the servings from food groups recommended daily. Image: USDAReporter Jane Black has a good overview of the upcoming revision of USDA dietary guidelines in today’s Washington Post. As she observes, Big Ag and Big Food typically resist any attempts by the government to give specific advice on which foods and how much of them you should eat. Black leaves it to nutritionist Marion Nestle — who wrote a book about her own experiences drafting a revision to the dietary guidelines in the 1980s — to sum the whole problem up: “The only time they talk about food is if it’s an ‘eat more’ message … If it’s a question of eating less, then they talk about nutrients.”

As a result, we get the off-kilter food pyramid that everyone knows and hates. You know, the one that says you can eat Froot Loops and M&Ms for breakfast, a cheeseburger for lunch, and three slices of pepperoni pizza for dinner and still be consistent with the pyramid.

And as Black points out:

Although most people do not read them, the guidelines have broad impact on Americans’ lives. They dictate what is served in school breakfast and lunch, in education materials used by SNAP — formerly called food stamps — and in the development of information on the nutrition labels of food packages. They also underpin education materials that are available in community centers, doctors’ offices and hospitals.

In some ways, I think the very existence of the guidelines has become deeply problematic: they have more or less become the government arm of the industrial-food marketing machine. The USDA’s primary role as promoter of American agricultural products seems to trump its responsibility to regulate those products from their food-safety or public and environmental health standpoints, just as it does its responsibility to provide dietary guidelines that might discourage the eating of some of those economic drivers.

So, remind me again: Why isn’t the Department of Health and Human Services in charge of nutritional guidance? Oh, right. Because then Big Food might get frozen out of the process.

Let’s not oversell the importance of the federal dietary guidelines. While they do affect things like the National School Lunch Program, the USDA isn’t bound by them. The government’s Institute of Medicine recently came out with its own set of dietary guidelines for school lunches that are mostly an attempt to get school meals into compliance with existing USDA guidelines. And what’s stopping the USDA from incorporating the institute’s recommendations? It’s not just industry lobbying — it’s the additional cost of a menu that features more vegetables, fresh food, and less meat.

The insufficiency of federal dietary guidelines is not the primary reason that Americans don’t eat enough vegetables — in fact, don’t eat particularly well at all — while kids get an astonishing 40 percent of their calories from solid fat and added sugar. American food consumption patterns are mostly about price signals and environmental cues. These point inevitably and totally toward the purchase of energy-dense, nutrient-poor, heavily processed food at the expense of fresh, healthy, mostly plant-based foods. If we really care about changing that, we need to look at ways to make the prices on supermarket shelves reflect our stated values as a society, and constrain food companies from surrounding us with marketing messages telling us — usually in total opposition to government guidelines — exactly what they really want us to eat.