Almost as soon as President Barack Obama and President Xi Jinping announced their landmark climate deal last week, there was a torrent of criticism that the pact let China off the hook. Incoming Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) complained that “the agreement requires the Chinese to do nothing at all for 16 years.” The argument goes like this: The U.S. committed to deeper, faster cuts than it had before — reducing carbon emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. But under the deal, the Chinese are allowed to spew greenhouse gases unabated, only committing to stop increasing those emissions “around 2030.”

Indeed, exactly how China will begin to “peak” its emissions around 2030 without a legally binding agreement is still an open question. Historically, there’s been widespread suspicion about China’s intentions on the issue — the country has, after all, been a thorn in the side of international climate negotiations for years. And even the White House appeared to raise an eyebrow at the staggering scale of the cleaner energy sources China would need to install to reach its goals: the non-fossil fuel equivalent of the “total current electricity generation capacity in the United States” over the next 16 years, the White House said.

But this week, China’s leadership has begun to answer that question. According to reports in state-controlled media, China’s State Council — essentially its cabinet — unveiled a new cap on annual coal use Wednesday. Under the new targets, China will limit coal consumption to 4.2 billion tons in 2020. That’s an increase from 3.75 billion tons last year. But relative to the country’s overall energy consumption mix, it’s a reduction; last year, coal accounted for around 67 percent of China’s energy consumption. Under the new plan, that figure would fall to 62 percent in 2020. The Xinhua report also says that the share of non-fossil fuels will rise to 15 percent by 2020 (from 9.8 percent in 2013) — a significant advance towards the goal of reaching 20 percent by 2030 outlined in the U.S.-China deal.

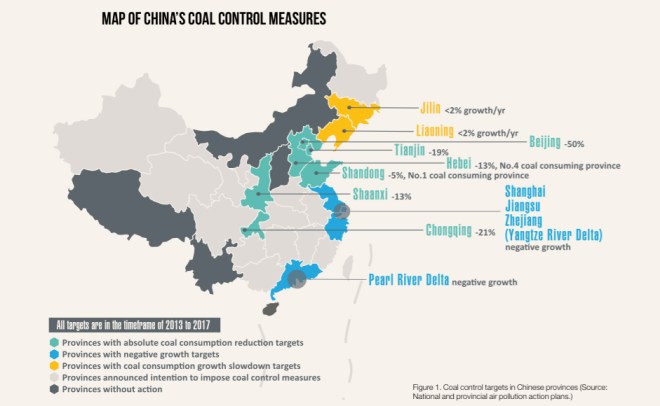

While the cap represents a big step politically — coming from the State Council — the new promises are consistent with current trends in China. Many provinces have recently introduced air quality policies that seek to reverse the rapid growth in coal use, according to a Greenpeace report released in April. Twelve of China’s 34 provinces, accounting for 44 percent of the country’s coal consumption, have already pledged to implement coal control measures, according to the report.

Twelve Chinese provinces have already pledged to implement coal control measures. Greenpeace

This week’s announcement is likely to cement China’s plans at the very highest levels of government — and it sends a signal to the international community that the country means business. The South China Morning Post reports that the new targets announced this week are likely to make their way into China’s official “five year plan” — a kind of economic development master plan that will be formalized next year and will dictate top-down strategy for 2016-2020.

While the climate benefits are obvious, and global in scope, the drivers behind the high profile announcement are far more domestic. The newspaper quotes Lin Boqiang, director of Xiamen University’s China Centre for China Energy Economics Research, as saying the early announcement can be linked to China’s desperation to do something about its air quality: “The smog crisis has forced China’s government to change its views on the country’s energy structure in the past several years. That’s why they want to release this blueprint now.”

Environmentalists have cautiously welcomed the plan but are pushing for more. “We think it’s definitely a positive sign, in line with what they’ve said they’re going to do,” Alvin Lin, an energy expert with Natural Resources Defense Council, told the New York Times. “We’d like to see it a bit lower than that, if you’re trying to meet the air pollution and air quality targets that they have set, and if you consider all the other environmental and health impacts of coal and the greenhouse-gas emissions of coal.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.