It’s springtime at the Point Reyes National Seashore, about an hour outside of San Francisco, and the cold wind whips off the sea and through the tall grass along the cliffs. Cows wander and graze along the fingers of land that reach out into the estuary’s tiny bays, an area altogether encompassing just over three square miles.

Beyond the estuary, at the outer edges of the seashore, seals sun themselves on the beaches, packed in tightly and squirming along the shoreline.

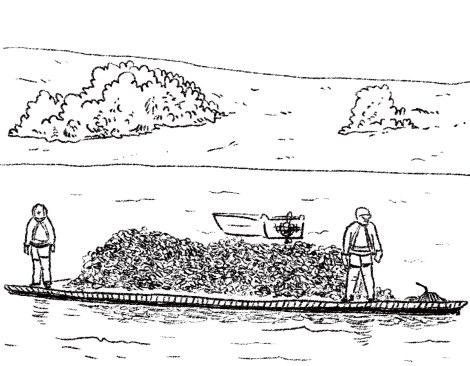

From March through June, the estuary is quiet. The seashore boasts more than 28,000 acres of agricultural land, most of it for beef and dairy production — but it’s pupping season for the seals, and the National Park Service has instated its annual ban on the motorboats that usually zip around the estuary, planting and harvesting millions of oysters for the Drakes Bay Oyster Company.

These estuary oysters have been here for decades, but their lease has run out. If the National Park Service gets its way, this estuary will soon be protected as pure wilderness, with no oyster farming allowed, and those seals will never hear a motor in this water again.

The Lunny family, which owns the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, has been fighting for years to stay put — the family’s appeal is due to be heard in court this week. But recently, this dispute has gotten caught up in national environmental battles, including the fight over the Keystone XL oil pipeline. Members of Congress and national green groups have weighed in. And what ultimately amounts to just two square miles of “potential wilderness” have split the environmental movement right down the middle, locally and nationally.

The battle for this estuary has become far more than a fight about an oyster farm — it’s become a flashpoint in the debate over what we want out of the natural world, and what we can afford. At a time of both economic and ecological crisis, how much sense does it make to put a fence up around nature? How much sense does it make to let business interests capitalize off public lands? And who gets to decide?

This is not a wholly unique dispute — conservation and agriculture have come to blows in the past, and often. But this fight has torn at one of the greenest communities in the country, a place where the local town center is papered in anti-Keystone XL posters and fliers for classes on switching to solar power.

Marin County, where Point Reyes is located, is the heart of the San Francisco Bay Area’s eco foodie obsession. The county was the first in California to offer a local organic label and is now home to over 20,000 acres of certified organic agriculture.

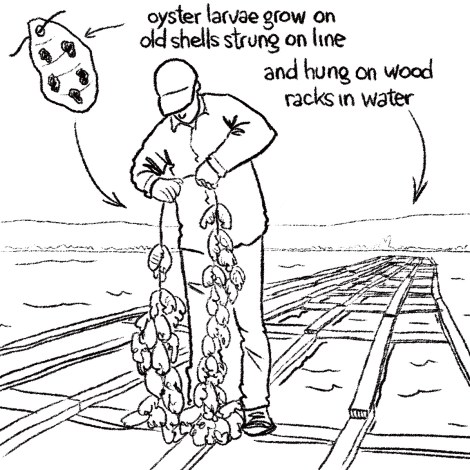

Proponents for sustainable, local food systems argue that local oysters are a healthy, ecologically friendly source of protein, grown close to home, with the added benefit of filtering the local water. Among them are critically acclaimed restaurateurs such as the owners of the Hayes Street Grill and celebrity chef Alice Waters, who have aligned themselves with the Sonoma and Marin County Farm Bureaus, the California Farm Bureau Federation, and Marin County’s agriculture commissioner.

Backing the National Park Service in its efforts to oust the oyster farmers are national conservation and parks protection groups, including the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council, as well as the California Coastal Commission. Notable conservationists including oceanographer Sylvia Earle have also weighed in to support increased protections for the shoreline and the ouster of the farm.

Both sides say they are motivated by a desire to protect the environment and be responsible stewards of the land. Both sides claim broad support, say science is on their side, and blame one another for campaigns of misinformation. From personal attacks to falsified reports to piles of lawsuits, it’s been salty and slimy, and it’s far from over.

It’s a Sunday morning and Brigid Lunny pushes up the sleeves on her Drakes Bay Oyster Company sweatshirt. She’s manning the register at the oyster shack, the spiffiest of a cluster of small buildings on a teensy plot of land perched on the shore of an inlet along the estuary. The farm’s workers live in the houses nearby — you can see their gardens and hear their backyard chickens.

According to local farm groups, the beds these workers tend in Drakes Bay produce nearly a third of all oysters grown in California. The oyster shack and picnic grounds along the shore also draw tens of thousands of tourists each year.

Starting early this morning, customers stream into the little white shack, coolers in hand, asking about the state of things, offering their support.

“How’s the fight going?” one man asks.

“Pretty good,” says Brigid, the granddaughter of owner Kevin Lunny, as she piles oysters into bags. “We have another court case in May, and who knows what that will bring.”

“Well I hope they go in your favor,” the man says, grabbing the bags. “This seems kind of ridiculous.”

“If anything was to go wrong with the environment because of the business here, it would’ve done so a long time ago. Not now,” Brigid says, shrugging.

She points to the nearby road and the gas-guzzling tourists driving along it, to the ranches nearby, to the kayaking businesses that operate in the same waters. “For me, that’s not wilderness,” she says. “It’ll never be wilderness.”

Almost 40 percent of the Point Reyes National Seashore really isn’t wilderness — it’s a “pastoral zone” in Park Service parlance, set aside for agriculture. The park was established in 1962, more than 100 years after many of the ranches on these lands were first started. It was a big conservation win during a time of development, but it was still an odd one. Existing ranches were allowed to stay by selling their land to the government and leasing it back.

The Philip Burton Wilderness Act of 1976 protected more of the seashore, but was no less confusing. While the act designated much actual and “potential” wilderness in the area, it also called for the preservation of other significant land uses: “recreational, educational, historic preservation, interpretation, and scientific research opportunities as are consistent with … preservation of the natural environment.”

In addition to the cattle ranches, there was also an oyster farm in these waters when the park was established — it had been there for almost 30 years. In 1972, the federal government bought out the Johnson’s Oyster Farm, offering a 40-year lease and a “conditional use” permit. But before that lease ran out, in 2004, Point Reyes rancher Kevin Lunny purchased the farm, expanded oyster cultivation to the other small bays in the estuary, and said he wanted to stay.

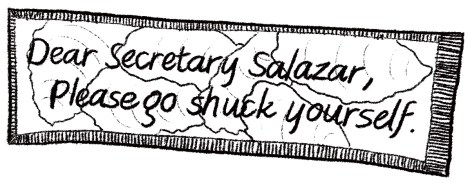

The Park Service has allowed for “non-conforming” uses in other wilderness areas — motorboats in the Grand Canyon, for example. But the Department of the Interior warned Lunny that the government was required by the 1976 act to convert the area to wilderness “as soon as the non-conforming use can be eliminated.” President Obama’s interior secretary, Ken Salazar, had the authority to extend the Lunnys’ lease, but declined, based on the 1976 “potential wilderness” designation and a controversial environmental impact study. On Dec. 4, 2012, Salazar officially deemed the estuary protected wilderness. The oyster farm would have to go.

The Lunnys sued to overturn the decision, and the farm has continued to operate these past few months thanks to an emergency injunction from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth District in San Francisco, which stated that “the balance of hardships tips sharply” in the Lunnys’ favor until the court can address “serious legal questions” about Salazar’s decision.

But it’s been the serious environmental questions swirling in the estuary that made this fight a national battle over how we use and protect public lands.

The dispute over the estuary is, in simple terms, a dispute over the Drakes Bay Oyster Company’s expired lease. But that doesn’t account for the cultural, philosophical, and scientific issues at play in Drakes Bay.

The Lunnys and their supporters contend that the oyster operation is completely sustainable and that the bivalves even help filter the estuary’s waters. Moreover, they say that Salazar, who recently left his post at Interior, had an “obsession” with getting rid of the farm. “In their obsession to eliminate the oyster farm, [Interior Department officials] abused the law, the facts, the science — and especially the oyster farm, its employees, and their families,” their lawsuit reads.

“Closing the Oyster Farm would have a broad, negative and immediate impact, on the local economy and the sustainable agriculture and food industry in the San Francisco Bay Area,” the farm’s supporters wrote to the court in March, adding that advocates for Drakes closure are “stuck in an archaic and discredited preservationist paradigm.”

Local biologist Phyllis Faber said the California Coastal Commission “has ‘lost its way’” in working with the National Park Service to remove the farm. “It has engaged in an inexplicable campaign — exceeding its charter — to bureaucratically smother — to drive out of business — a working family farm.”

“I’m not going to say that it makes no impact at all,” says Brigid Lunny, leaning against the counter, oyster knife in hand. “But having these buildings torn down seems like more of an impact than just leaving them, you know?” When she talks about the hypothetical end of the farm, she tears up. “We’re a good family; we’re stewards of the land.”

This kind of talk rankles Amy Trainer, executive director of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin.

“Not only is this operation wholly incompatible with wilderness, to say it’s sustainable is just a joke,” says Trainer, pointing to a bevy of charges against the farm, from non-native oysters choking protected eelgrass, to motorboats running seals off the shoreline, to farm waste dumped in the estuary. “I think those claims are hollow, and it does a real serious injustice to the number of truly great sustainable agricultural operations in Marin.”

From the conservationists’ perspective, this isn’t about food versus wilderness — it’s about a business versus the people.

“Every piece of land can’t be everything to everyone. That’s not what national parks were created for,” says Neal Desai, associate director of the National Parks Conservation Association’s Pacific regional office. “We can grow oysters elsewhere. But we can’t have another place to protect the marine wilderness.”

“There’s no question that the environmentally preferred alternative for this area is for it to be restored to wilderness,” Trainer tells me. “Get the 19 million non-native oysters out. Get the pressure-treated wood racks out. Get all the plastic bags out. Stop the motorized boat trips. Stop the disturbance of harbor seals. Stop all these adverse impacts.”

Two blocks from Trainer’s office, a storefront window proudly displays this bumper sticker.

For nearly 10 years, each side in this debate has thrown whatever it can at the other. Every environmental impact report, every scientific study, and every claim has been debated. The National Park Service itself reprimanded some of its own scientists for biased and even false reporting aimed at booting the farm.

But as nasty as the local fight got, no one expected the conservative D.C. political machine to jump into the Drakes fray.

In late 2012, the relatively new government watchdog group Cause of Action offered pro bono legal assistance to the Lunnys. Cause of Action says it is nonpartisan, though critics point to the fact that the executive director formerly worked with the Koch brothers. (The group’s donor list is secret.)

“We have an interest in exposing how the Department of the Interior used taxpayer dollars to purposefully misrepresent science in an effort to harm an existing small business,” says Cause of Action spokesperson Mary Beth Hutchins.

Other support has been even more problematic. Republican Sen. David Vitter of Louisiana recently tacked a proposal to extend the farm’s lease to a bill that would expedite the Keystone XL pipeline and oil drilling in Alaska. The Lunnys have readily accepted Cause of Action’s assistance — hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal aid help — but have distanced themselves from Vitter’s bill, emphasizing their ethos of sustainability.

Conservationists, though, see a slippery slope: Let the farm stay on the public lands, and that could give legal precedent next time for an oil company. “It’s been very interesting to see the company that this business is keeping in trying to achieve its agenda,” says Trainer. “Their agenda is clearly free-market fundamentalism — open up public land, anti-regulation, anti-restrictions on use of public property.”

There are multiple outstanding lawsuits seeking to save the farm, with the first set to be heard in court beginning May 14. This battle could rage all year, and beyond — enough time for the Lunnys to grow another crop of oysters.

But regardless of whether this oyster farm goes, the Point Reyes National Seashore will not ever really be wilderness — the pastoral lands are here to stay. When Salazar decided to give Drakes Bay Oyster Company the boot, he also extended all ranching leases from 10 to 20 years. Conservationists point to the powerful shellfish lobby that’s rallied to save the oyster farm, but the big agriculture muscle here is clearly in the cows.

One-quarter of the county’s cattle live on this land, overrunning the park trails. Standing water pools that reach down into the mudflats are full of acid-green algae. Runoff from the cliffs above flows down onto the beaches in slimy green trickles.

“If the ranching has impacts, those should be managed to the extent possible,” says Desai, with the National Parks Conservation Association. “Can more be done? I’m sure. Has this actually been addressed? Probably not. The park has been focused on this oyster farm issue.”

The park has been focused on other threats, too — far greater ones. “Rising sea levels impelled by melting glaciers and polar icecaps will likely dramatically change this coastal park’s environment upon which animals have come to rely and humans come to enjoy,” reads the park’s mission statement on climate change. This is the horrific future fate against which both sides of this battle are ostensibly trying to hedge. If we stand to lose it all, maybe we should build that tall fence — but how much does it matter if we save it but can only appreciate it from distance?

The green movement is arguably bigger and more diverse than ever, and our wild places and arable lands are fewer and further between. The battle for Drakes Bay might be a small one, but it could be indicative of how these fights will continue to play out on public lands, from now until this estuary has slipped under the rising tides.

Correction: This article originally misspelled Brigid Lunny’s name. We’ve fixed the error.