Days after Republicans ethered Democrats in this year’s midterm elections, many are still scratching their heads over the Maryland’s governor race, where the once-sure-shot Democratic candidate Anthony Brown lost to Larry Hogan, the GOP’s once-sure-nobody who has never held elected office. OK, many people are not wondering about this, it’s really just me.

Maryland is one of the bluest states (Hogan is only the second Republican governor in the last 50 years) that has built a reputation for being one of the greenest on the back of its popular, twice-elected Gov. Martin O’Malley. Brown is O’Malley’s lieutenant governor of eight years, and was the governor’s appointed successor (had the electorate agreed) since O’Malley is term-limited. Brown’s platform was basically a copy-and-paste of O’Malley’s, with emphasis on education and the environment.

Brown’s advantage didn’t stop there: He had over four times as much money to spend as Hogan in a state where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans two-to-one. He led in every poll; FiveThirtyEight gave him a 94 percent chance of winning. He had the endorsement of every major Democratic stalwart in the state. President Obama came down to stump for him, for better or worse, but more importantly, Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton stumped for him as well. How the hell did Brown fuck this up?

According to the dozens of commentaries I’ve read about this race, there’s almost unanimous agreement that it boiled down to this: Brown ran a very bad campaign; Hogan ran a very good campaign. As Philip Bump wrote at The Fix, “Brown lost to the candidate that the voters preferred, simple as that.”

I’ve had a hard time accepting the simplicity, but after talking to a number of political scientists, environmentalists, and residents in Maryland, I concede. OK, Brown beat himself.

But what is there to learn from what Brown did wrong and from what Hogan apparently did right? Exploring those questions leads me to two prominent features of this race — one seen, one unseen — that have heavy implications for those of us who are concerned about transitioning toward a clean-energy, pollution-free future that’s based on justice.

Let’s take the visible feature, first:

Blame Brown’s loss on the rain:

While there were numerous reasons for why Brown’s campaign was so terrible — outlined cleanly here by blogger and former Baltimore Sun reporter Barry Rascovar — many are literally blaming it on the rain.

Specifically, some pundits, particularly at the national outlets, are pointing at Maryland’s “rain tax” as Brown’s albatross. No, Maryland does not tax its rain, but it does collect fees from homeowners and businesses to help the state manage stormwater runoff, which is one of the biggest sources of contamination in the Chesapeake Bay. Hogan’s campaign exploited angst against the stormwater management fee, rebranding it as a “rain tax,” and turned the race into a referendum on O’Malley’s tax-and-spend administration. Brown had little to do with the policy, but Hogan tagged him in every O’Malley meme as complicit.

Alec MacGillis reported in the New Republic that “every single voter” he spoke with in Baltimore County brought up the rain tax. Matt Yglesias credited it as the reason Democrats lost Maryland. A beautician named Shannon Laue derided it as a reason she voted for Hogan in the Baltimore Sun. And then there’s Kandie, an African-American woman the Hogan campaign featured in a video to further hammer the Democrats on their “tax on rain”:

The so-called rain tax is a policy created to help heal one of the most polluted harbors in the nation. The stormwater fee is required under a bill passed by state legislators and signed into law by O’Malley in 2012. It is just one part of a broad-scale strategy to help clean up the bay that involves the federal government and other states in the Chesapeake watershed like Virginia and Pennsylvania. The state is mandated by the EPA to implement strategies to curb its Chesapeake pollution.

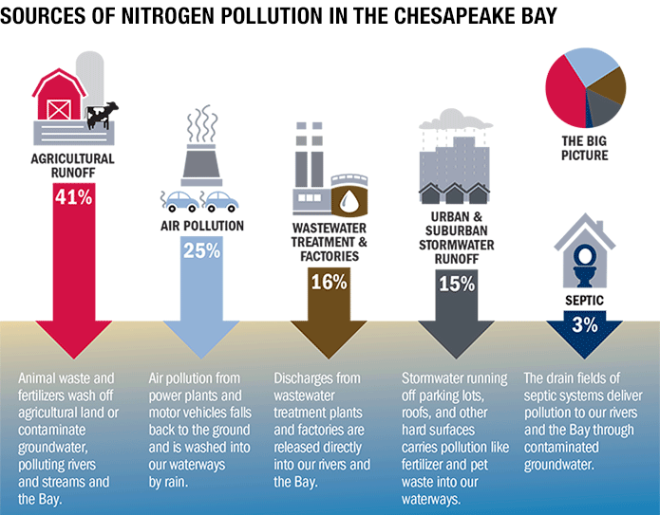

The arrow you want to pay attention to in the above infographic is the one labeled “Urban & Suburban Stormwater Runoff.” The stormwater management fee is applied for the impervious surfaces such as rooftops and driveways that racetrack rainwater into our waterways, along with all the chemicals and pollution the rain picks up along the way. It’s an annual fee applied in 11 counties — the rate varies per county, but it’s $39 for a single family home in Baltimore County — the proceeds of which are used to create stormwater capture projects like rain gardens.

The policy is loved by progressives, liberals, environmentalists, and the Chesapeake’s protectors alike. And yet, it probably wasn’t the best way to handle the stormwater pollution problem. Here’s why:

1. It’s inflexible. Roy Meyers, an environmental policy professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, says one of the major flaws of the policy is that, “there’s no way to reduce your tax burden if you come up with ways of mitigating stormwater runoff at your home.” Meaning, for example, if you install equipment in your roof that captures the rain, preventing runoff, you still have to pay the stormwater fee. This obviously won’t endear voters.

2. It shifted the cost burdens of cleaning the Chesapeake to homeowners. Patuxet Riverkeeper Fred Tutman was particularly miffed about this when I talked to him, saying the stormwater management fee should have been applied to real estate businesses and developers that create the impervious surfaces to begin with. “Why should [homeowners] have to pay for [real estate’s] bad practices?” said Tutman, who teaches environmental law and policy at St. Mary’s College. “They put an extra bill on the end users, people who didn’t make these problems, when they know we get better environmental practices when you apply penalties on the businesses that actually build these systems.”

3. It handed Republicans a cudgel for Brown. Of the eleven counties tasked with administering the fee, a few were Republican, meaning they were against it from the gate. Combine that with the problems above and you have a recipe for disaffection and a new weapon handed to Republicans looking to fell Democrats over taxation.

So the storm water management fee didn’t do Brown any favors. But was that really enough to explain why almost 13 percent of voters from the four counties that Brown won bolted for the Republican candidate this year? Philip Bump notes that this strongly suggests that Brown’s loss can’t be explained purely by low voter turnout, but rather by O’Malley voters shifting support to the GOP. Which leads me to the unseen feature of this race.

Brown’s skin color wasn’t a factor, which means it was.

On a public radio roundtable about this race the other day, one of the panelists (I don’t have his name or a link — sorry I was driving) brought up that Brown downplayed race — his blackness — in this campaign. Instead, he trumpeted his qualifications as a Harvard-trained lawyer and his military experience. In 2010, the prominent African-American candidate Artur Davis ran for governor in Alabama downplaying his blackness as well. He lost.

One of the listed reasons why Brown’s campaign ran so poorly is that people barely saw him. He didn’t show up for debates, held few press conferences, evaded reporters, and disappeared this summer, according to Rascovar.

Was this a deliberate thing? Did his campaign staff and consultants think it was a good idea to keep Brown out of the public eye, possibly so voters would forget that he was black? I know the question itself sounds silly. Still, if O’Malley became popular for constantly attending public events and pressing the flesh, why didn’t the campaign staff push Brown to do the same?

Regardless, Brown lost despite the fact that his campaign was the policy twin of O’Malley’s. But as Maryland state Sen. Jamie Raskin told the Washington Post, “The bottom fell out among white voters in Baltimore County.”

Were white Democrats really so hot about the “rain tax” that they threw their party under the bus for a Republican political novice? If so, why didn’t Maryland voters have any complaints about the $2.6 million in public campaign funds Hogan took from the state to run. He did this because the typical big spenders on Republican races didn’t believe in him enough to invest in his race.

I obviously can’t prove that there was some kind of Bradley Effect in Maryland, but I do know this: There have been few African Americans elected historically in statewide campaigns, especially in the South, where the only African-Americans popularly elected statewide since Reconstruction are Doug Wilder, governor of Virginia for one term (1990-1994) and Sen. Tim Scott, who won in South Carolina this week, and with little help from black voters.

I’ll concede that, given Brown’s mistakes, racism among voters was likely not the prevailing factor in this race. Still, the question keeps swirling in my head: If Brown was white, would he have won on Tuesday? We’ll never know.

Either way, there are important takeaways from this race for those pushing for a more just energy future.

- No matter how environmentally benevolent the policy, the design matters. Meaning, reducing pollution or producing cleaner energy won’t mean much if the costs are passed to consumers. Those of low-income end up taking it the hardest and that’s a sure way to turn people away from your campaign, no matter how progressive.

- No matter how democratic the campaign, race matters. When people claim that race doesn’t matter, racism always ends up proving them wrong. There’s no way to mute race, so it might as well be addressed purposefully. The racism might be overcome, albeit not easily. But it can’t be done by evading people altogether, like Brown did.

Let Maryland be a lesson to all environmentalists hoping to push their agenda and for the candidates of color they support.