On a hot morning in July, Ray Apy stood in a vacant lot in upstate New York and pointed to the mowed grass, explaining what he wanted to build there: a pilot plant to convert waste into something useful. He tipped the contents of a small glass jar into his cupped palm, revealing tiny black pellets the size of peppercorns.

The pellets were a substance called biochar. It’s created by heating organic matter — any substance originating from plants, animals, or other organisms — at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen. This turns it into a charcoal-like substance that can be sold as an additive to concrete or soil — and, crucially, locks carbon inside.

Heralded as “black gold,” biochar promises to dispose of waste, enrich soil, and fight climate change, all which has made it the darling of the growing carbon removal industry. A 2018 report from a panel of United Nations scientists estimated the world will need to remove between 100 billion and 1 trillion metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere this century to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). Most carbon removal technologies are still nascent: Direct air capture — fans that suck carbon out of the air — has received a lot of media attention and investment, but has only delivered 250 tons of carbon removal, per an industry tracker. By contrast, dozens of biochar start-ups have delivered several hundreds of thousands of tons.

For Apy, a tech entrepreneur who earned a master’s degree at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, biochar primarily represents a way to ethically deal with waste while making a valuable product, fertilizer. “I didn’t create this business to address climate change,” he said. “It just happens to check that box in a big way.”

Lori Van Buren / Times Union

In 2021, Apy was excited when a local economic development company invited him to pitch the project to Moreau, a town of 16,000 people located about 40 miles up I-87 from Albany tucked in a bend of the Hudson River. Apy attended 10 meetings with the Moreau Planning Board, two of which were public, and one with the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, or DEC. In 2022, the planning board granted Apy’s company, Northeastern Biochar Solutions, approval to build in their 30-year-old industrial park, vacant but for a formaldehyde plant chugging across the drive. The facility would be known as Saratoga Biochar Solutions, or just Saratoga Biochar.

In recent years, Moreau and surrounding towns have lost hundreds of industrial jobs, as a cement factory and paper mill shuttered across the river in Glens Falls within two years. This small biochar plant promised to create green new jobs and produce a locally useful product. The project was even enthusiastically supported by town supervisor Todd Kusnierz, a rising star of the New York State Republican party. The biochar looked like a win-win-win — for the town, the climate, and Saratoga Biochar.

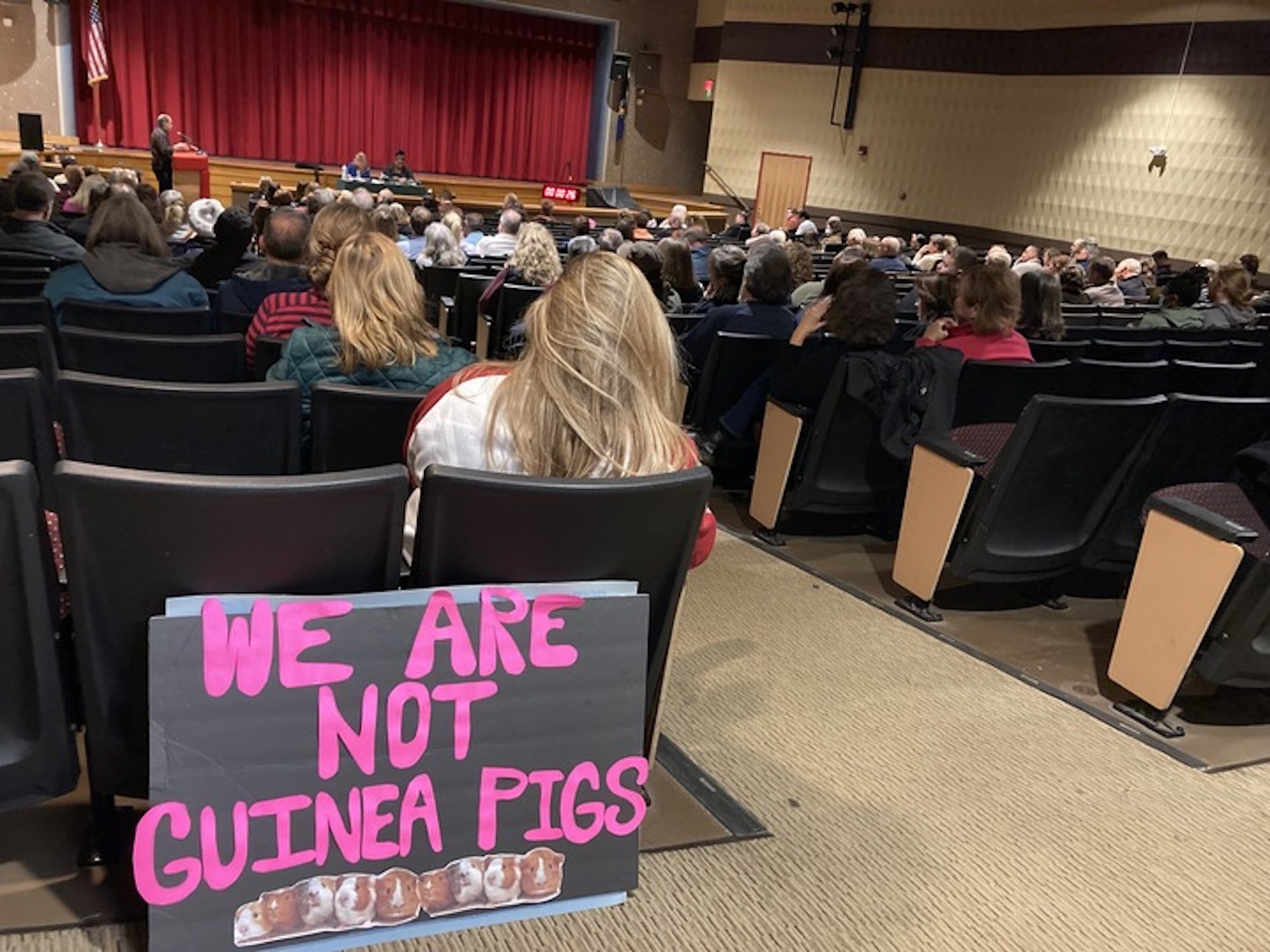

But from Apy’s perspective, what should have been a routine permitting process was beginning to unravel. He encountered bile and sign-waving from protestors claiming to be environmentalists who wanted his plant to fail. The political upheaval that ensued included a challenge in the New York Supreme Court (which Saratoga Biochar won, pending appeal); allegations that children were tricked into signing a pro-biochar petition; reported bullying at gas stations; and neighbors putting up pointedly hostile lawn signs. Last November, Kusnierz was ousted in a 3-to-1 landslide by a challenger backed by Democrats and a grassroots clean air coalition who staked this, the “most important local election” of voters’ lifetimes, on blocking biochar. One of the new town board’s first actions: placing a nine-month moratorium on any new industrial building in the town.

What went wrong?

Wendy Liberatore / Times Union

To put it bluntly: poop. Saratoga’s novel biochar plant would run on human biosolids, otherwise known as sewage sludge. The facility would take in 75,000 tons per year of byproducts of treated wastewater from toilets across New York state and New England that would otherwise be bound for overflowing landfills or, in the greater Moreau area, the polluting Wheelabrator incinerator in Hudson Falls. Moreau residents feared Saratoga Biochar would put odors and dangerous chemicals in their air — potentially adding to a health burden caused by decades of pollution from other industrial facilities.

In the grassy lot, Apy knelt on the faded asphalt and laid out the thick scroll of permitting documents prepared more than a year earlier, which detailed the plant’s construction down to a chart specifying which trees would be planted (pin oak and thornless cockspur hawthorn). So far, nothing has been built.

The fate of Saratoga Biochar shows that proposed climate solutions can’t get off the ground without consent from the communities that will bear the brunt of their trade-offs — especially when those communities have a history of being harmed by industry pitching win-win solutions.

Moreau is set high on bluffs overlooking the Hudson River. The water looks tempting and cool during a summer heatwave, but conceals a dark chapter in the town’s living history.

In 1942, General Electric opened a capacitor plant in Fort Edward and Hudson Falls, two towns neighboring Moreau, promising to manufacture engines to beat the Nazis with good union jobs. But over its 30 years in operation, the GE plant swilled PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), which have been shown to cause cancer in animals and are considered probable human carcinogens, into the Hudson River and dumped industrial waste into pits in Moreau. In 1983, The New York Times wrote of Moreau, “If there is such a thing as a typical town plagued by toxic waste, it may be this one,” interviewing residents complaining of skin rashes, miscarriages, and cancer that they feared could be linked to the dumping. The PCBs, which resist degradation in the environment, caused genetic deformities in local fish populations, including tomcod, and created a Superfund site stretching 200 miles downriver to the southern tip of New York City. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency still monitors the local GE Caputo Superfund site, treating groundwater in a GE-funded operation expected to last 200 years.

Mike Groll / AP Photo

Moreau still has big industrial neighbors. Driving around the surrounding region, Apy pointed out the Finch Paper mill across the river in Glens Falls and the tall pipe of the Wheelabrator incinerator in Hudson Falls, one of the top 10 emitters of mercury per ton of incinerated waste in the country, and the number one emitter of lead per ton.

In Hudson Falls, average annual emergency room visits for the inflammatory lung disease COPD are higher than 86 percent of the state; in Glens Falls, they are 96 percent higher.

About 10 miles from the industrial park where Apy hoped to build, on a sun-dappled road that swoops along the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains, Ann Purdue, a lawyer with expertise in transportation systems, lives with her husband Tom Masso, now retired after a career in operations and marketing. They moved here several years ago from Washington, D.C., a homecoming for Purdue, who grew up in the Adirondacks. As a member of the town planning board, which reviews permit applications, Purdue first encountered Saratoga Biochar’s proposal in December 2021. She was immediately cautious.

For Purdue, Moreau is a town with little experience hosting heavy industry within its municipal boundaries, unlike its neighbors, and thus had little experience permitting such projects.

“This particular project … on its face sounded like a great idea — a solution for a serious problem,” Purdue said. “And then you find there are a lot of unknowns. And the question is who is going to encounter or suffer the impacts of the unknowns if they’re adverse?”

Wendy Liberatore / Times Union

Over 90 minutes, sitting in her high-ceilinged living room, Purdue narrated Saratoga Biochar’s permitting process and the community’s protest movement with the exactitude and documents of a deposition, including a letter she’d written to the state DEC claiming that importing 15 percent of the state’s sewage sludge to the town presented a “grossly disproportionate environmental burden” upon a community still suffering from GE’s pollution.

For Purdue and Masso, who also opposes the plant, these burdens include diesel-burning trucks barreling past schools on local roads at a frequency approved 30 years ago, before residential neighborhoods grew up around the industrial park. And potentially dangerous and smelly air emissions from a technical process that Purdue and Masso said was untested, apart from an “inadequate” 2019 test batch (which produced the biochar pellets in Apy’s bottle).

Masso went upstairs to retrieve folded copies of the Post Star, a local newspaper, containing investigations into Apy’s business partner, Bryce Meeker, who previously worked for a Nebraska facility that turned corn into ethanol until it was shut down in 2021 for pollution, groundwater contamination, and a pattern of regulatory problems. Meeker and Apy, Purdue and Masso concluded, were not prepared to run an expert, ethical operation in their town. (Meeker told Grist he was a consultant for the project, and left the role two years before the plant received any violations.)

On the planning board, Purdue advocated for an outside environmental consultant, who was not ultimately hired, and argued that Saratoga Biochar was not providing adequate documentation to ensure the plant was safe. In the spring of 2022, while the planning board was debating the site plan, the neighbors were finding out about it and getting worried.

Gina LeClair, who lives on a street of modest houses so close to the industrial park that its backyard trees are sketched on Apy’s plans, first learned of Saratoga Biochar’s plans from a short local newspaper story in April 2022, two weeks before the second public meeting. “I just knew this is big,” she said, “and there’s still people that haven’t heard about it.”

A former member of the five-person town board — Moreau’s elected legislative body — LeClair said the community and even some town board members had been in the dark about the deal as the planning board prepared to approve it. “Residents were told, ‘This is a done deal,’” LeClair said. “We responded, ‘This is not done until we say it’s done.’”

LeClair set up the Not Moreau Facebook page, some of whose posts have received 9,000 views, and reached out to neighbors across party lines and throughout the surrounding communities. A concerned neighbor had contacted Tracy Frisch, chair of the Clean Air Action Network of Glens Falls, who had experience fighting industrial projects in the area. They built a coalition that included New York State Assembly member Carrie Woerner, the environmental law group Earthjustice, the student law clinic at Pace University, and a large local real estate developer.

The coalition staged a series of protests, standing on roadsides with their children in bright yellow T-shirts printed with “Not Moreau,” a motto on signs still planted on many of the lawns in front of the houses on streets surrounding the industrial park. Hundreds of protestors turned out at the August 2022 meeting where the planning board voted to approve the permits, crowding the room and hallways carrying signs that read “No Biochar,” per local media. Some left chanting, “This is not over.”

Courtesy of Tianna Bubello

The “Not Moreau” campaign cast its sights on the November 2023 town election, urging voters to elect candidates who opposed the biochar project. Ultimately, 76 percent of Moreau voters cast ballots for the town supervisor candidate backed by the anti-biochar coalition. Voters also ousted town board members who had previously voted to approve the project. In April 2024, the new town board passed the nine-month moratorium on all industrial building while the town reassessed its zoning regulations.

“It’s been a real community thing,” LeClair said, tearing up over how everyone had come together. “I don’t think it’s the norm. I think it’s the small groups, and they fight, and they hope,” she concluded. “It’s the biggest thing I ever did in my life.”

But the protest movement’s victory — and its methods — were not universally supported in Moreau. Kyle Noonan, a current town board member, favored the plant for the jobs and tax base it would create — and said that he faced open hostility from formerly friendly neighbors for taking that position.

Courtesy of Gina LeClair

An Earth science teacher, Noonan had read up on biochar and was persuaded the method was not only safe, but innovative. “I was excited that maybe the town of Moreau was going to be part of this first carbon sequestration process that was going to take this growing problem of more sewage, more sewage, more sewage, and do something with it,” he said. He said he found it perplexing that the protestors blocking the plant claimed to be environmentalists and ignored expert testimony in favor of what he read as misinformation.

“They lined our streets with their children holding up posters saying, ‘You’re going to give us cancer,’” said Noonan.

Following the moratorium, whether or not the plant would get built in the long run hinged on three all-important approvals from the state — an air permit, a solid-waste management permit, and a so-called beneficial-use permit — that Apy had yet to receive. In February, the DEC held two nights of hearings, both in person and virtually, to receive public comments on the project.

The night before the first hearing, Frisch organized an information session for dozens of community members. They listened as the experts shared information about today’s class of “forever chemicals,” per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS — which sounded eerily similar to the PCBs that had plagued their town for decades. Commonly used in water-resistant products, these molecules consist of long chains of carbon atoms bound to fluorine, a hardy chemical linkage that is hard to destroy, and which allows them to persist in our water, blood, and guts. PFAS are used in all kinds of products, including carpeting, pizza boxes, shampoo, and dental floss. They’ve been tied to multiple health issues, including higher risks of certain cancers, hormone disruption, and developmental delays in children. They are also found in high concentrations in sewage sludge, partially from what gets flushed down toilets including menstrual products, toilet paper, and human waste, as well as from industrial wastewater that gets mixed in at a wastewater treatment plant.

Wendy Liberatore / Times Union

It’s only recently that PFAS have come under regulation. In 2022, Maine became the first state to prohibit the still-common practice of spreading raw sewage sludge on agricultural fields due to its PFAS content. And last April, the EPA announced that it would require water treatment plants to limit six common types of PFAS in drinking water.

Some Moreau residents were worried about the Saratoga Biochar plant emitting noxious smells, and about diesel exhaust from trucks. Some people were worried about nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, and even heavy metals wafting into the town’s air. But the possibility of breathing in PFAS emitted from the plant became a flash point for the town. For Frisch and many residents, PFAS came to define the scientific case against Saratoga Biochar.

At the information session, Denise Trabbic-Pointer laid out that case in front of community members. A former DuPont chemical engineer of 35 years, Trabbic-Pointer now volunteers with the Sierra Club to support communities exposed to toxic chemicals. Her first slide title that night read: “Caution! The SBS [Saratoga Biochar Solutions] Proposed Facility will be a Grand Experiment with the Community as the Guinea Pig.”

Trabbic-Pointer warned that while the imported sewage sludge’s chemical composition was unknown, it would undoubtedly contain PFAS. She listed health impacts linked to the chemicals, including hypertension, preeclampsia, asthma, and heart and lung disease. “I worked in Teflon [a product that contains PFAS], so I can tell you that I’m rotting from the inside out,” she said. Later, Trabbic-Pointer described walking past vats of Teflon while pregnant with her daughter, who also suffered health problems. At the end of her presentation, a community member asked if his well water might become contaminated with PFAS because of Saratoga Biochar. “It’s likely,” Trabbic-Pointer responded. “It can happen.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a community traumatized by another class of forever chemicals, residents latched onto these PFAS concerns, and it became a common point in most public comments about the plant’s permit approvals. It was striking for Apy; his plant is a solution to the PFAS crisis, he said, not the cause.

“They just refuse to believe the science — it’s like science denial,” he said. Opponents of Saratoga Biochar aren’t “taking the time to read all the information that is right there in the permit applications. It leaves really nothing to question.”

Jeff Hutchens / Getty Images

The only known way to loosen PFAS’ tight molecular bonds is to heat them to extreme temperatures — a minimum of 2,012 degrees F, according to the EPA. Many incinerators that burn sewage sludge after it goes through treatment don’t get that hot. Notably, the local Wheelabrator incinerator is only required to maintain an operating temperature of 1,500 degrees F.

But Saratoga Biochar’s proposed pilot plant would get blisteringly hot — hot enough to break down PFAS. Apy explained that the PFAS would first get separated from the biosolids in the pyrolysis step — when the sludge is heated in the absence of oxygen. At that point, the forever chemicals become gases, leaving the biochar itself relatively clean of PFAS — “We’re counting 99 percent or better,” he said. Then, as a gas, the PFAS would be sent to a thermal oxidizer that Apy said would operate at 2,300 degrees F, high enough to destroy the PFAS.

Apy isn’t the only one to herald biochar as a promising way to destroy PFAS.

Gerard Cornelissen, a researcher at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, began working on biochar in 2009 as a way to enrich soils and sequester carbon, and later came to see it as a way to help destroy the forever chemicals, which he called the “most pressing contaminant problem” in the world. In several scientific articles, Cornelissen has shown that pyrolysis can remove PFAS in biosolids and make them undetectable in the final biochar product, with less than 1 percent of the chemicals escaping in exhaust. Cornelissen said he’d feel comfortable if a biochar plant were built next door to him. Still, he cautioned that his team, operating on the cutting edge of analytical science, could measure only 56 of the more than 12,000 PFAS compounds. He noted that most techniques missed the smaller PFAS molecules (or “short chain” PFAS), which are likely to be less dangerous, but whose effects are still generally unknown — a concern also raised by Trabbic-Pointer.

“From all the integrity that I’ve got as a scientist, I think it’s the best we can do,” Cornelissen said. “But it’s not 100 percent perfect, either.”

Back at the DEC public comment hearing, Joe Peranio of Glens Falls was one of the few community members to bring up climate change during his time to speak — out of more than 500 public comments. “Something that we should all be able to agree upon is that we need to take serious action in the effort of cleaning up our planet,” he said, explaining that, among other things, he wanted to counter the false idea that “biochar is not a valid solution for mitigating climate change.”

The science on biochar’s carbon-removing abilities is “well established,” according to Cornelissen. Independent studies have shown that biochar sequesters about 50 percent of the carbon contained in plants — which, if burned or left to rot, would otherwise end up in the air as part of the natural carbon cycle. Biochar made from sewage sludge isn’t as well studied, but it has also been shown to sequester carbon. Apy shared an analysis by an environmental consulting firm that concluded the Saratoga Biochar plant would be carbon-negative.

However, in a letter on behalf of the Clean Air Action Network, Earthjustice attorney Michael Youhana and his team took aim at this analysis, arguing, among other objections, that whether or not the plant removes carbon depends on the biochar’s end use. They questioned whether using biochar in fertilizer really results in permanent carbon storage, writing, “the greenhouse gas implications of land application of biochar are highly uncertain.” Many academics, on the other hand, argue that biochar added to soil will sequester carbon semi-permanently. Biochar made by Indigenous people in the Amazon basin centuries ago is still holding its carbon firmly in place.

Times Union

Although most speakers at the DEC hearings didn’t bring up climate change by name, they did refer to New York’s landmark 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which aims to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions 85 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. Pyrolysis, the process that produces biochar, is characterized as a greenhouse gas net producer under the law — and projects involving pyrolysis are not eligible to generate state-certified carbon offsets. Furthermore, critics of Saratoga Biochar said the plant would violate an environmental justice provision in the law.

Youhana explained the act requires that “disadvantaged communities,” identified by the New York State Climate Justice Working Group as having a critical number of pollution and public health burdens, not be disproportionately burdened by the energy transition. Any project that increases net emissions of conventional pollutants in these communities is banned under the law. Although Moreau doesn’t meet the state’s definition of a disadvantaged community, neighboring Hudson Falls and Glens Falls do, and Earthjustice and the Clean Air Action Network argue Saratoga Biochar will waft additional air pollution into these towns. While Earthjustice has successfully fought industrial projects across New York state using this provision, including a natural gas plant in Queens, Saratoga Biochar is the first climate solution the group has challenged — an “important test case,” said Youhana.

Apy said that while he respects the Climate Leadership and Protection Act’s mandate, he is concerned that the law will slow progress on needed climate projects precisely where they are needed, along with green jobs. He also said there will not be any undue air pollution burden on the towns neighboring Moreau. Youhana argued that Saratoga Biochar’s calculations are a best-case scenario, creating additional burden on the community if something does go wrong.

Times Union

No community wants to be a climate solution’s guinea pig, especially for an untested technology: No other biochar project in the country uses sewage sludge as the base of its product, and Saratoga Biochar has never built a small-scale version of the system it’s planning to use at its facility. The town would rely on pollution assessments from state environmental regulators, who require testing only every few years. And importantly, this type of plant has never been built at scale in the United States. What could persuade a town to take on that risk? Biochar from poop might be worth it for the climate, the country, and even the state — but what could make it worthwhile for the town of Moreau?

Johannes Lehmann, a Cornell University professor of soil biogeochemistry, is known as the biochar pioneer. He first began working on biochar as a method to improve soil fertility in the late 1990s, and he carried out seminal studies demonstrating that the material durably locks away carbon, introducing biochar as a carbon removal solution.

Lehmann declined to comment specifically on Saratoga Biochar, but he did offer an idea about win-win-win solutions — one that’s familiar to engineering students learning to serve communities. You don’t start with the technology, but rather with the problem, Lehmann said. “And then you work from how you can make this into a solution to serve the problem that people are having on this very localized level.”

By way of illustration, Lehmann described a project his Cornell team has developed for a dairy farmer near Ithaca. The project pyrolyzes cow manure into fertilizer and provides energy for the farm. It’s custom-built to address this farmer’s problems, and the end use for the biochar, as a soil additive, is under his control. But how can you scale this principle up to a town, a state, or a country? Particularly given, as Lehmann said, “You need to be able to articulate the problem, and most people can’t even do that.”

For Moreau, the local problem of what to do with PFAS-containing, greenhouse gas-emitting sewage sludge does need to be solved: Apy said sewage sludge removal in the Hudson Valley has the highest costs nationally, with landfills now charging $220 per ton, compared to roughly $100 four years ago. But Moreau’s residents are convinced that importing sewage from around the state and New England would not mitigate — only add to — their problems, particularly with a technology unproven at scale.

Ultimately, the DEC had similar concerns. In mid-November, the state agency sent a letter to Apy denying Saratoga Biochar’s three permit applications. The agency’s underlying argument was that Saratoga Biochar’s laboratory tests could not predict the impacts of a full-scale “permanent” plant. “While the proposed technology shows promise,” the DEC wrote, “there are too many unanswered questions about the effectiveness of the process and too little information about its safe implementation at an industrial scale.” The agency also determined that Saratoga Biochar could not claim carbon removal from biochar as an offset for the plant’s emissions under New York’s state climate law.

“We are jubilant that the DEC denied all permits for the disastrous sewage sludge biochar plant proposed in the town of Moreau,” Frisch wrote in a statement for the Clean Air Action Network. “This was the right decision.”

Purdue called the 500 public comments “critical” to the DEC decision. For her part, LeClair, founder of the Not Moreau Facebook page, credited the permit denial to her community’s activism. “This could never have happened if thousands of people of Moreau … and the surrounding communities had not supported it,” LeClair said, by collecting and signing petitions, planting yard signs, writing letters, doing research, and telling one another what they’d learned.

The fate of Saratoga Biochar shows all that can happen when an experimental technology that looks good on paper meets the neighbors — and when communities long responsible for taking on the burden of industrial waste are asked to take on still more. Even in the name of climate change.

Apy said that Saratoga Biochar would not appeal the DEC’s decision. Rather, he said, his company was looking to the future, focused on developing new projects in New York state: smaller-scale plants to be sited alongside municipal wastewater treatment facilities looking for “better outcomes for their biosolids.” Apy added, “We just want to get our technology out there and prove it.”

Correction: This story originally mischaracterized the operational status of the Finch Paper mill, misstated the distance between the industrial park and Ann Purdue’s house, misidentified the party who first contacted Tracy Frisch about the biochar project, and mischaracterized Denise Trabbic-Pointer’s work at DuPont and with the Sierra Club.