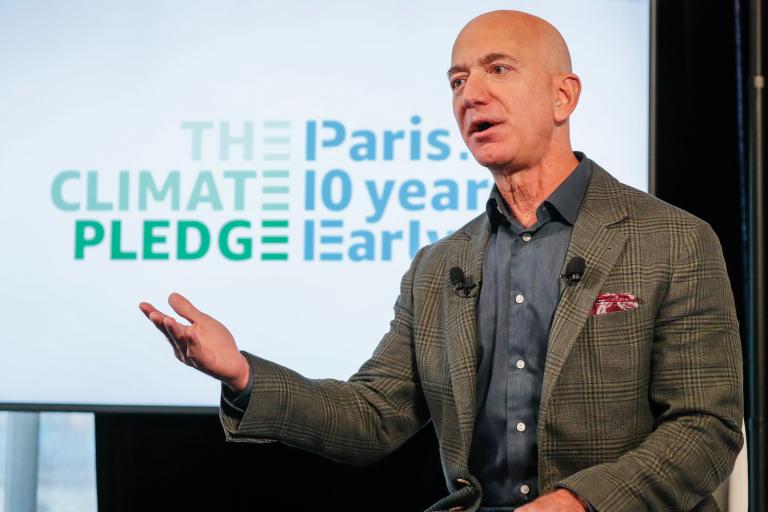

Big oil companies love to talk about a cleaner future — and how they’re going to make it happen. Over the last two years, Shell, BP, Chevron, and ExxonMobil have pledged to zero out their carbon emissions by 2050. Watching Exxon’s algae-heavy advertisements, you’d think the company is swapping oil barrels for biofuel farms. Shell’s website is sprinkled with pictures of solar panels and claims that it’s taking action to create “a more sustainable, renewable, energy-rich, lower carbon future.”

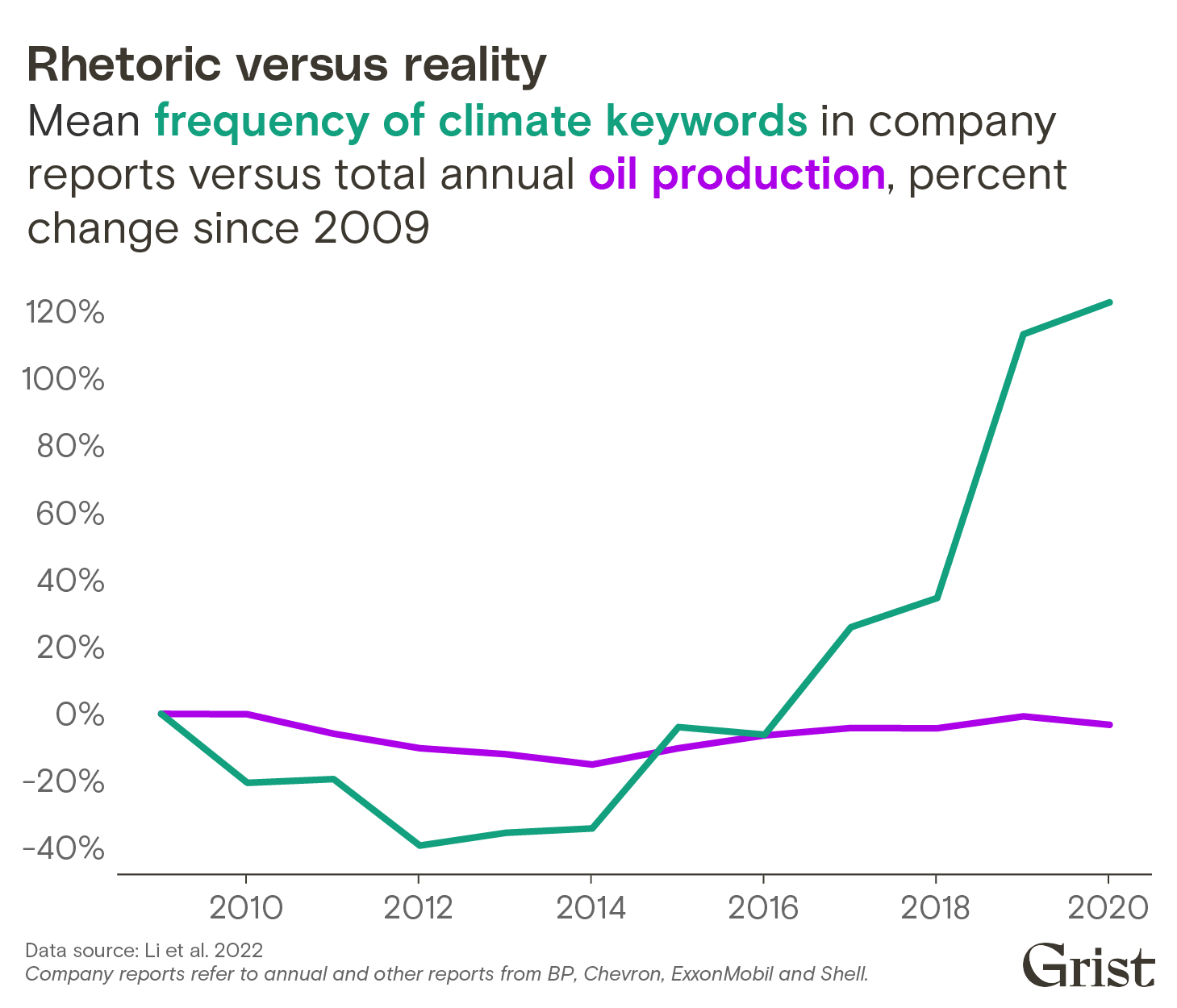

At a closer look, however, all this starts to seem hollow. According to a recent study published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One, there’s a big disconnect between oil companies’ words and behavior when it comes to climate change. Researchers in Japan analyzed how those four big oil companies, accounting for 10 percent of global carbon emissions since 1965, talked about climate change in their annual reports from 2009 to 2020. Then they scrutinized whether the companies had taken concrete measures to cut down on fossil fuel production and to shift their business to clean energy production.

What they found is that these oil companies have increased fossil fuel production and expanded exploration while making only surface-level investments in clean energy.

“There’s a lot of talk now, and there was a lot of talk in the past, but especially in the long period that we looked at, there’s been very, very little action,” said Gregory Trencher, a coauthor of the study and an environmental studies professor at Kyoto University in Japan. His team’s research provides the most comprehensive analysis to date on whether oil companies are actually moving away from fossil fuels.

In the last decade, oil companies have begun talking about the climate more than ever before — a trend reflected in their annual reports. Shell’s use of the phrase “low-carbon energy,” for instance, increased more than eightfold from 2009 to 2020. Over the same period, BP’s rhetoric related to making a clean-energy transition rose a similar amount. But that has yet to translate into concrete action: Fossil fuel production has remained relatively steady over the last decade, and from 2015 until the pandemic in 2020, most of the oil majors actually increased fossil fuel production. Shell, for instance, went from producing around 1,358,000 barrels of oil a day to 1,752,000.

Environmental advocates have long accused oil companies of “greenwashing” — putting a climate-friendly face in front of the public while continuing to drill for more oil behind the scenes. The recent study provides solid evidence for those accusations, concluding that “no [oil] major is currently on the way to a clean energy transition.”

Chevron and Exxon’s spending on clean energy was so insignificant it was “almost absent,” said Trencher, with Chevron spending a mere 0.23 percent and Exxon 0.22 percent of their total capital expenditures — the money a company uses to buy and maintain its physical assets — on developing low-carbon energy from 2010 to 2018. As for Exxon’s algae efforts, it turns out the company has spent more money on corporate advertising ($500 million between 2009 and 2015) than on its research into the biofuel ($300 million since 2009). Only BP and Shell met the researchers’ conservative benchmark of spending 1 percent of their capital expenditures on clean energy efforts.

In terms of electricity generated from clean energy sources, BP has made the most progress of any of the oil companies — but even then, its global renewables capacity only adds up to 2,000 megawatts, the equivalent of about two gas-fired power plants.

If oil companies were truly trying to switch to clean energy, Trencher said, you’d expect to see a shrinking emphasis on fossil fuels in their everyday business — such as a slowdown in searching for new oil and gas reserves. The study didn’t find convincing evidence that this was happening. BP and Shell have promised to reduce their investments in new fossil fuel extraction, but at the same time, they’ve expanded the territory where they explore for oil. In 2020, Shell’s undeveloped exploration territory went up by almost 15,000 square miles from the year before. The company’s target of reducing exploration by 2025, Trencher said, may have “triggered a rush before the deadline for them.”

Mei Li, a co-author of the report, suggested that the ability to continue profiting from fossil fuels was the chief reason that oil companies haven’t lived up to their climate promises. Wall Street is more likely to reward quarterly profits than moves to overhaul a business over the long-term. “They do not have the incentives to force them to make a clean energy transition,” Li said.

In response to the report, oil companies pointed to their climate promises but offered little in the way of proof. Exxon said that it planned to play “a leading role in the energy transition,” Chevron noted that it aimed to spend $10 billion on lower-carbon investments by 2028, and Shell pointed to its goal of becoming a “net zero emissions energy business by 2050.” BP said the study didn’t take its full progress into account since most of the data the researchers analyzed only ran through 2020, when the company first laid out its strategy to cancel out emissions.

Trencher said he wasn’t aware of any new pledges that would significantly change their findings and pointed to historical trends as reason to take oil companies’ promises with a grain of salt. “These companies have not been anywhere near as serious about climate change and decarbonization as their words have been,” he said.

The study follows previous research that has shown that oil companies spread misinformation about climate science, tried to shift the blame for climate change from fossil fuels to individuals, and tried to stop governments from taking action to curb carbon emissions. In the three years following the 2016 Paris Agreement, for example, the five largest oil companies spent more than $1 billion on lobbying against climate legislation and on rebranding themselves as climate-conscious combined, according to data from the think tank InfluenceMap.

As these things often do, the explanation for this contradictory behavior mostly comes down to money. “It’s sort of difficult for a company to have a justification to destroy its own business model,” Trencher said. “If we want to force these companies to abandon a fossil fuel-based business model, then that obviously has to be done through policies.”