This story was published in collaboration with The Bitter Southerner and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

Transcript

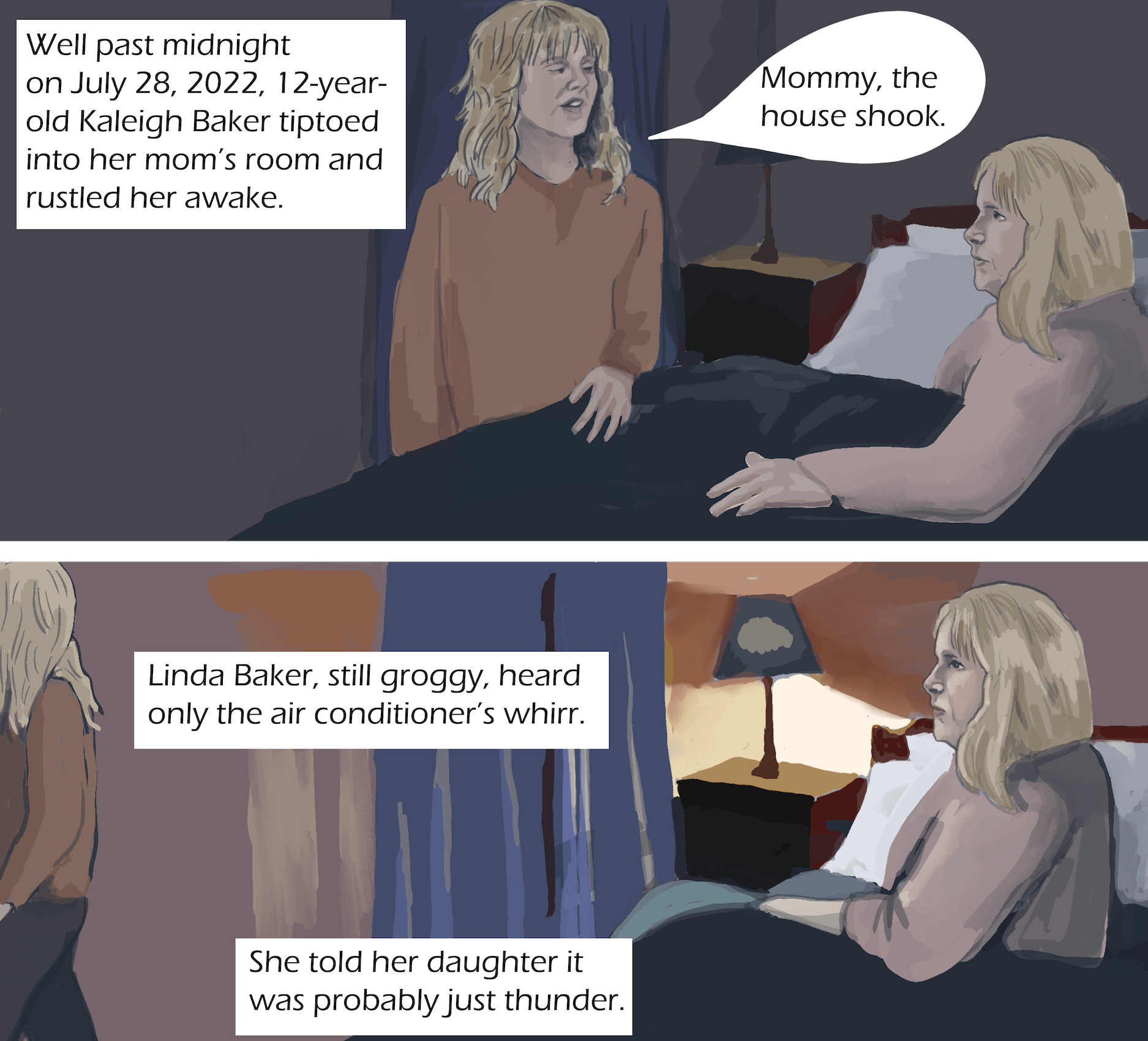

Well past midnight on July 28, 2022, 12-year-old Kaleigh Baker tiptoed into her mom’s room and rustled her awake. “Mommy, the house shook,” Kaleigh said.

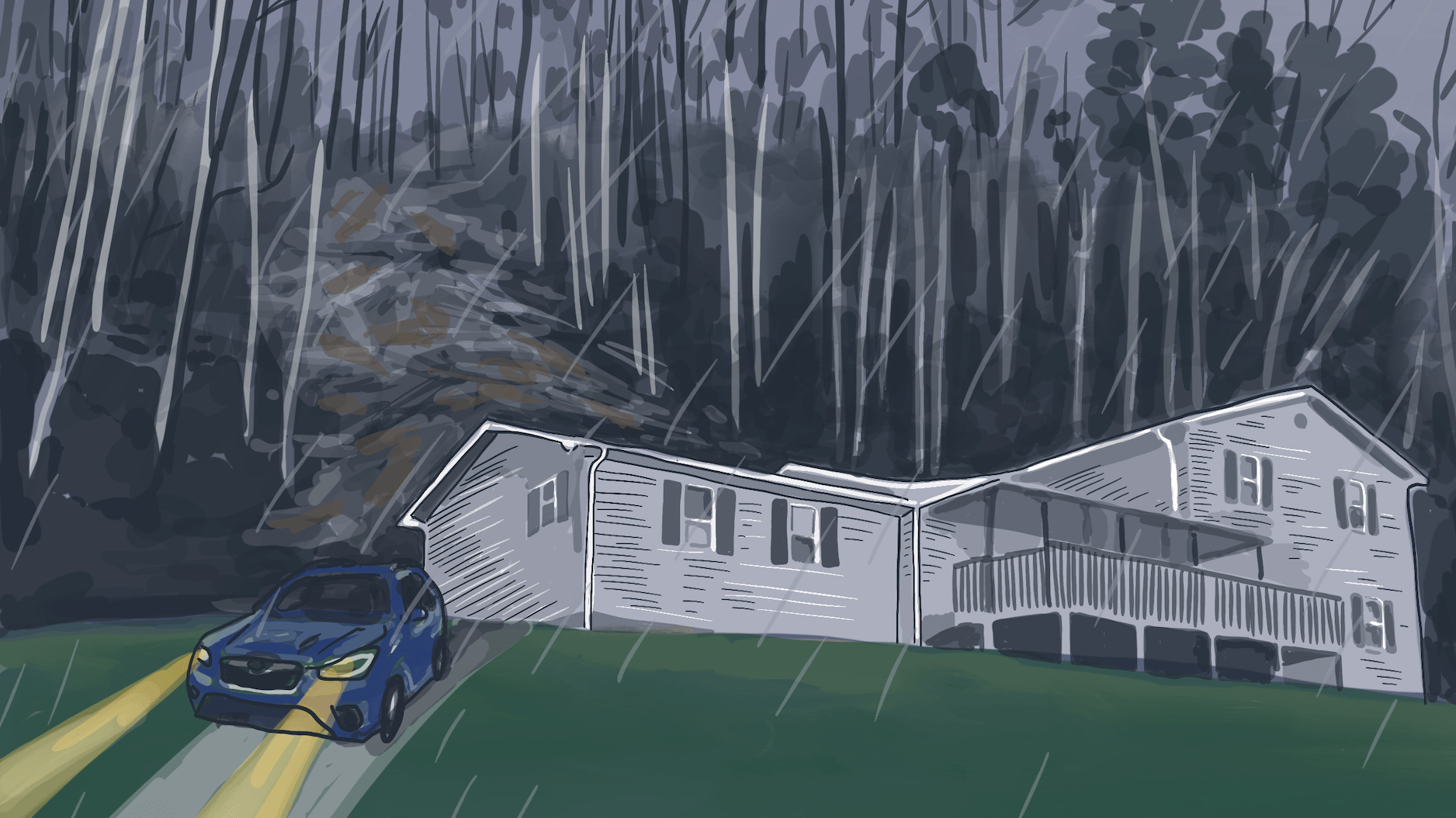

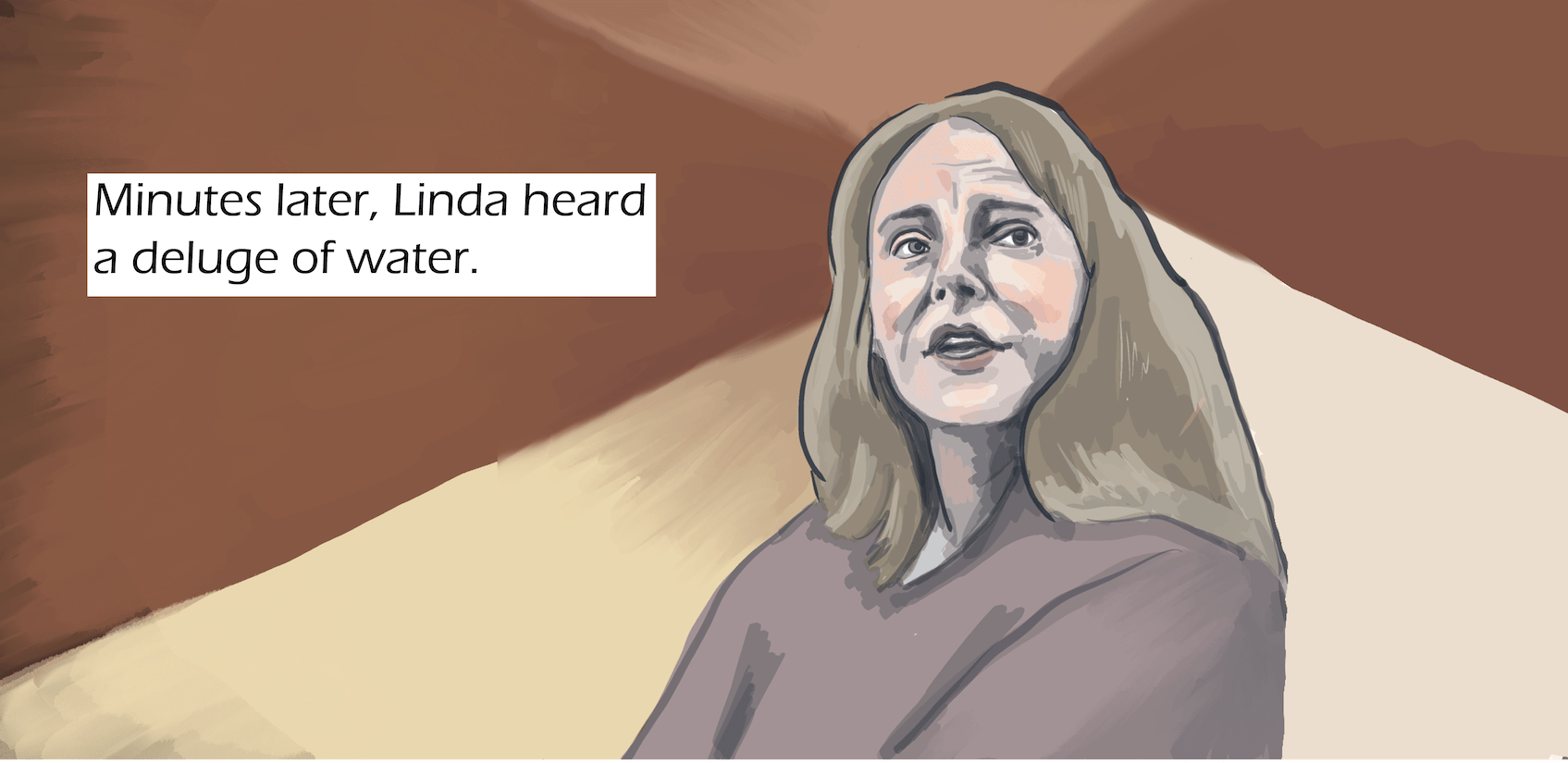

Linda Baker, still groggy, heard only the air conditioner’s whirr. She told Kaleigh it was probably just thunder. Kaleigh crept back upstairs. Minutes later, Linda heard a deluge of water. From the back door, she saw rain pounding down on a wall of mud almost 8 feet tall that had slammed against their home’s vinyl siding. Linda recognized the disaster: another landslide.

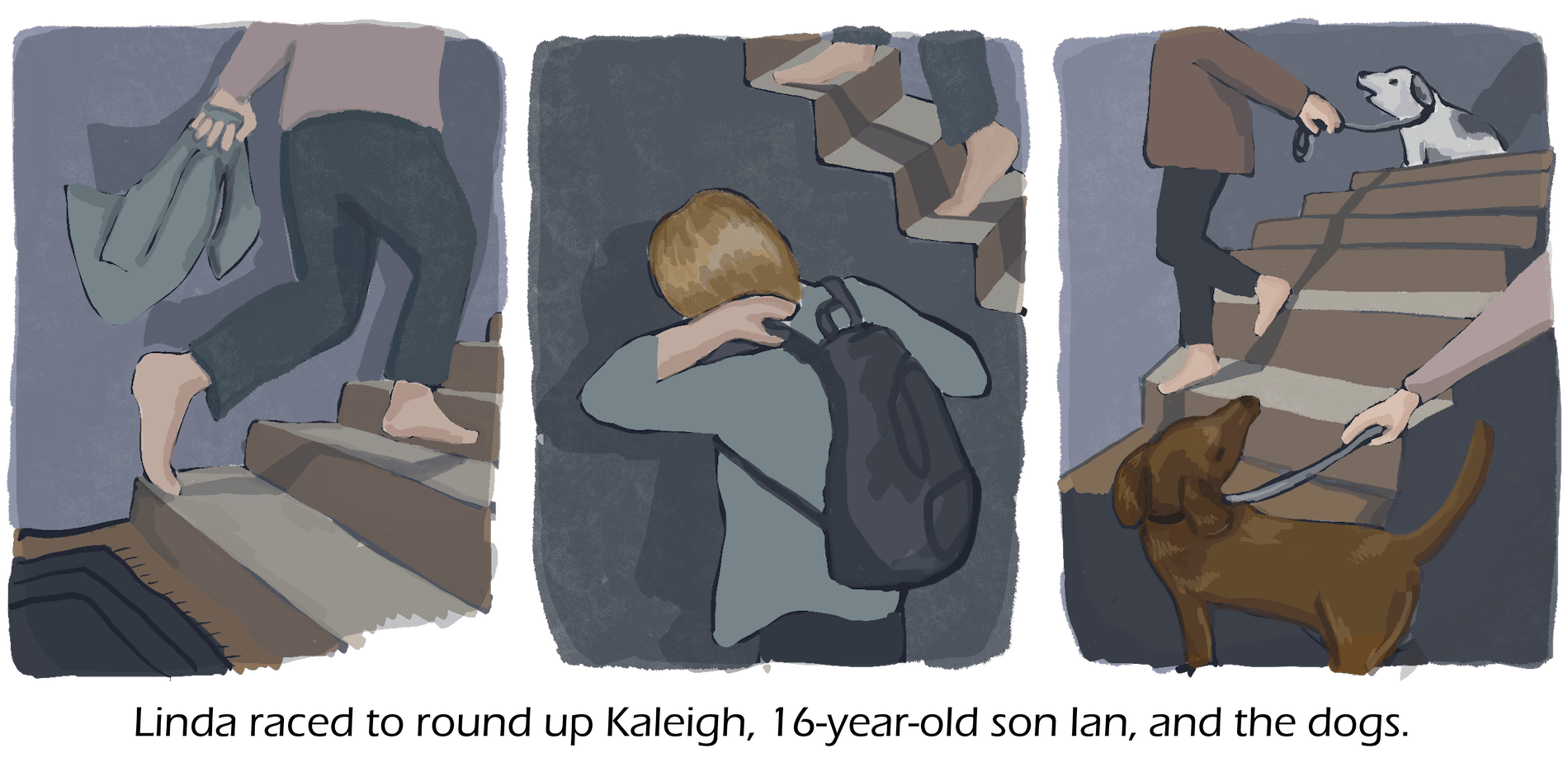

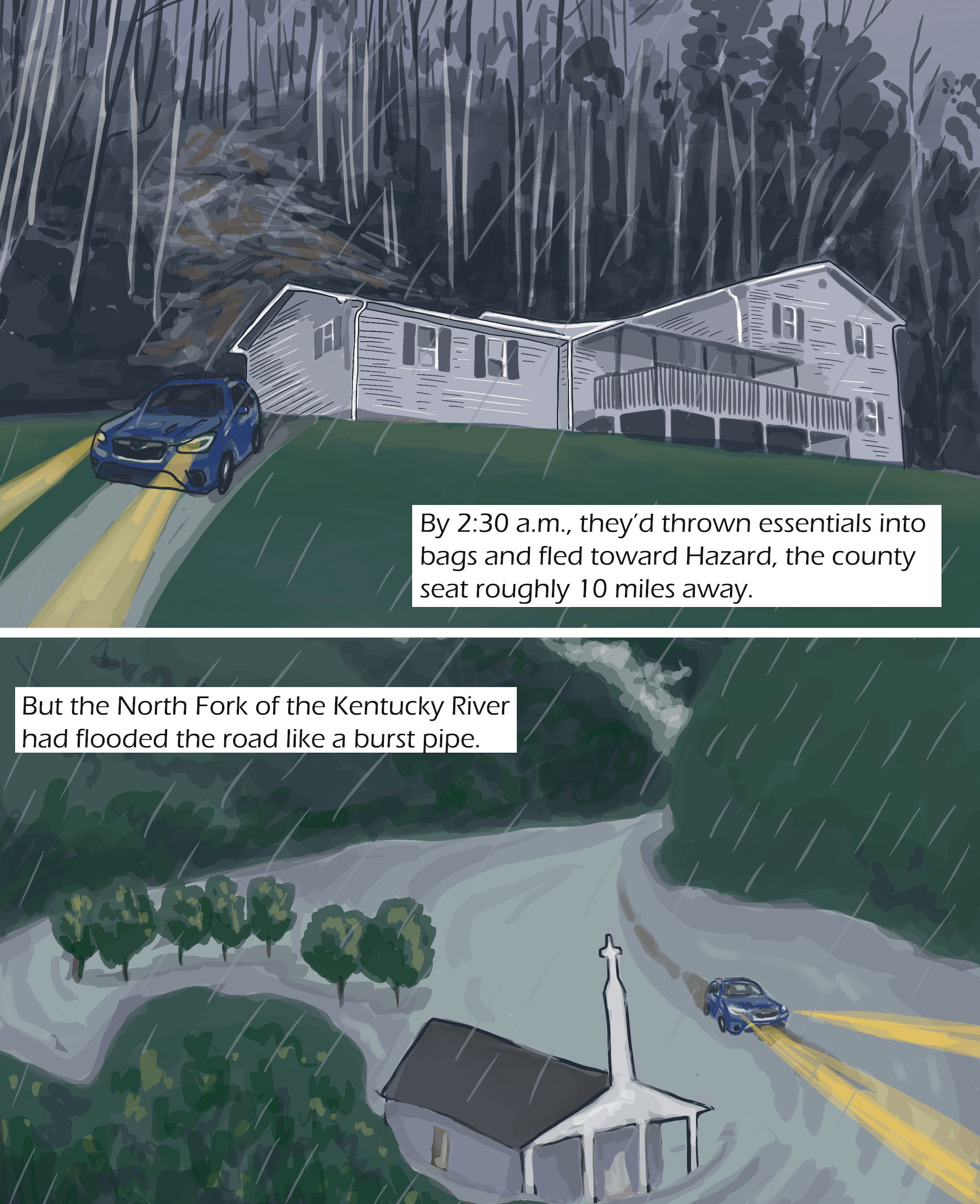

Linda raced to round up Kaleigh, 16-year-old son Ian, and the dogs. By 2:30 a.m., they’d thrown essentials into bags and fled toward Hazard, the county seat roughly 10 miles away. But the North Fork of the Kentucky River had flooded the road like a burst pipe. Water swept over the hood of the car and pushed the vehicle toward the river raging below.

Linda floored her car in reverse and, once clear, slowly retreated. Before they lost cell service, Kaleigh texted a friend, “I think I’m going to die tonight.”

Transcript

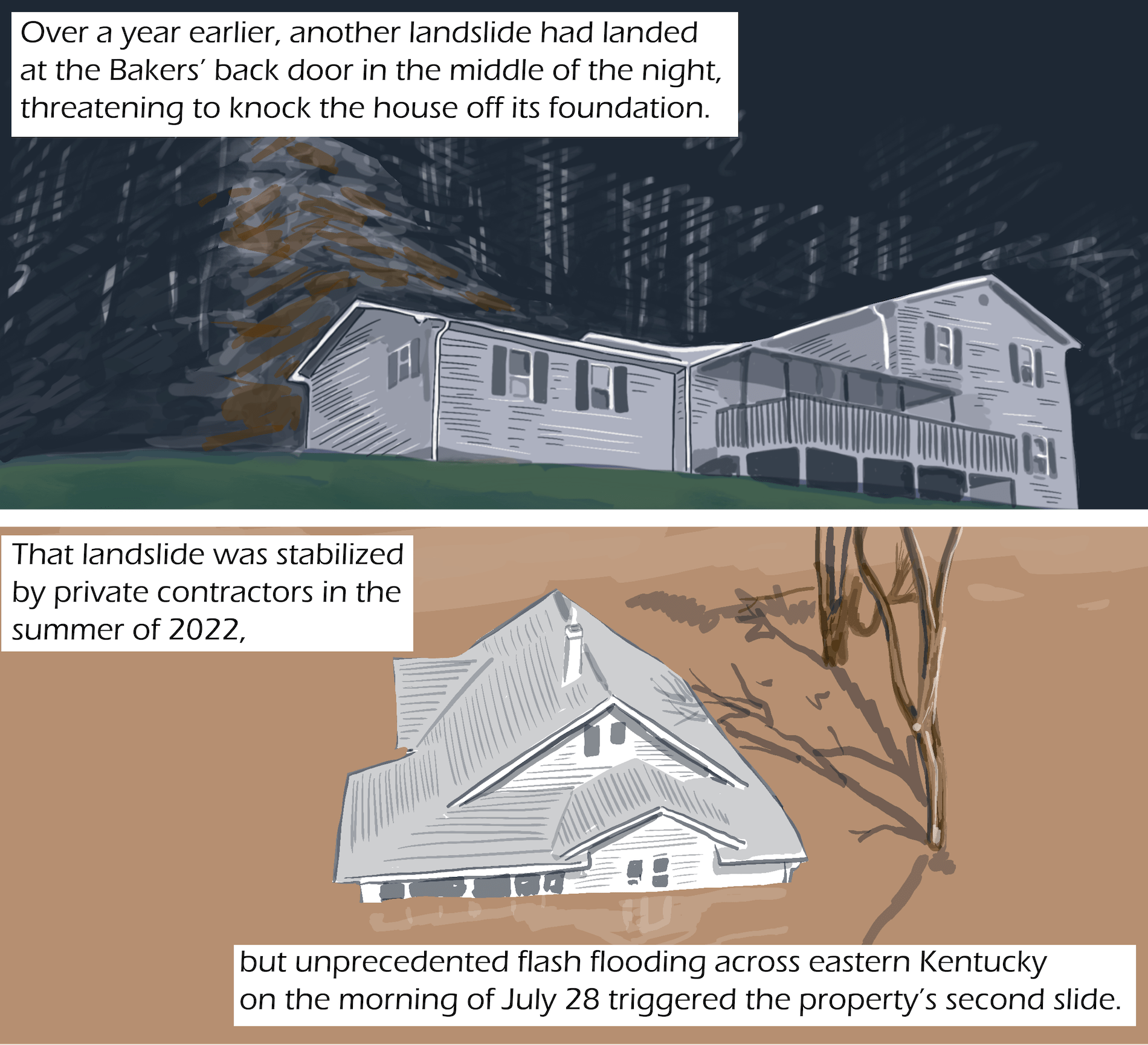

Over a year earlier, another landslide had landed at the Bakers’ back door in the middle of the night, threatening to knock the house off its foundation.

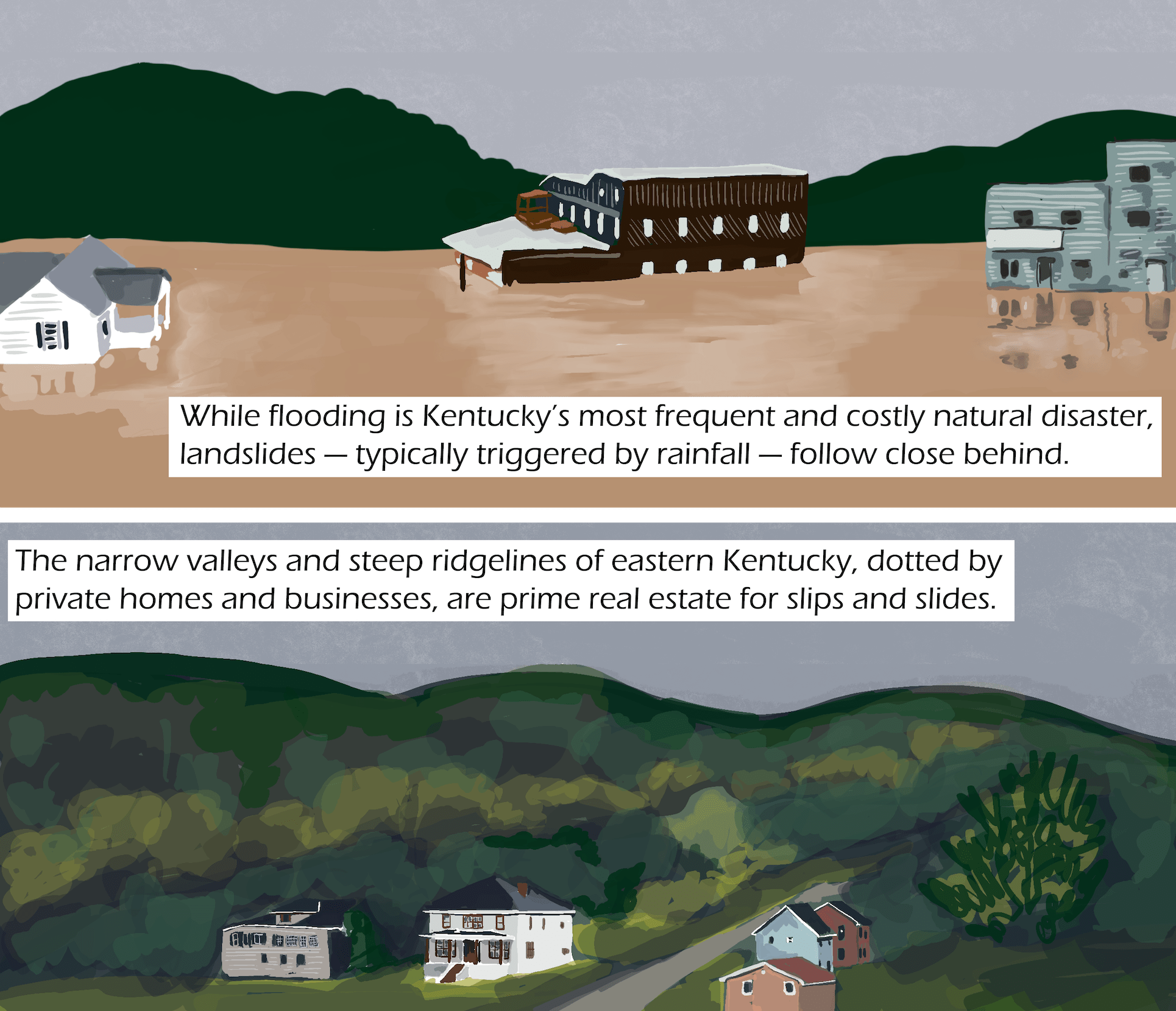

The landslide was stabilized by private contractors in the summer of 2022, but unprecedented flash flooding across eastern Kentucky on the morning of July 28 triggered the property’s second slide. While flooding is Kentucky’s most frequent and costly natural disaster, landslides — typically triggered by rainfall — follow close behind.

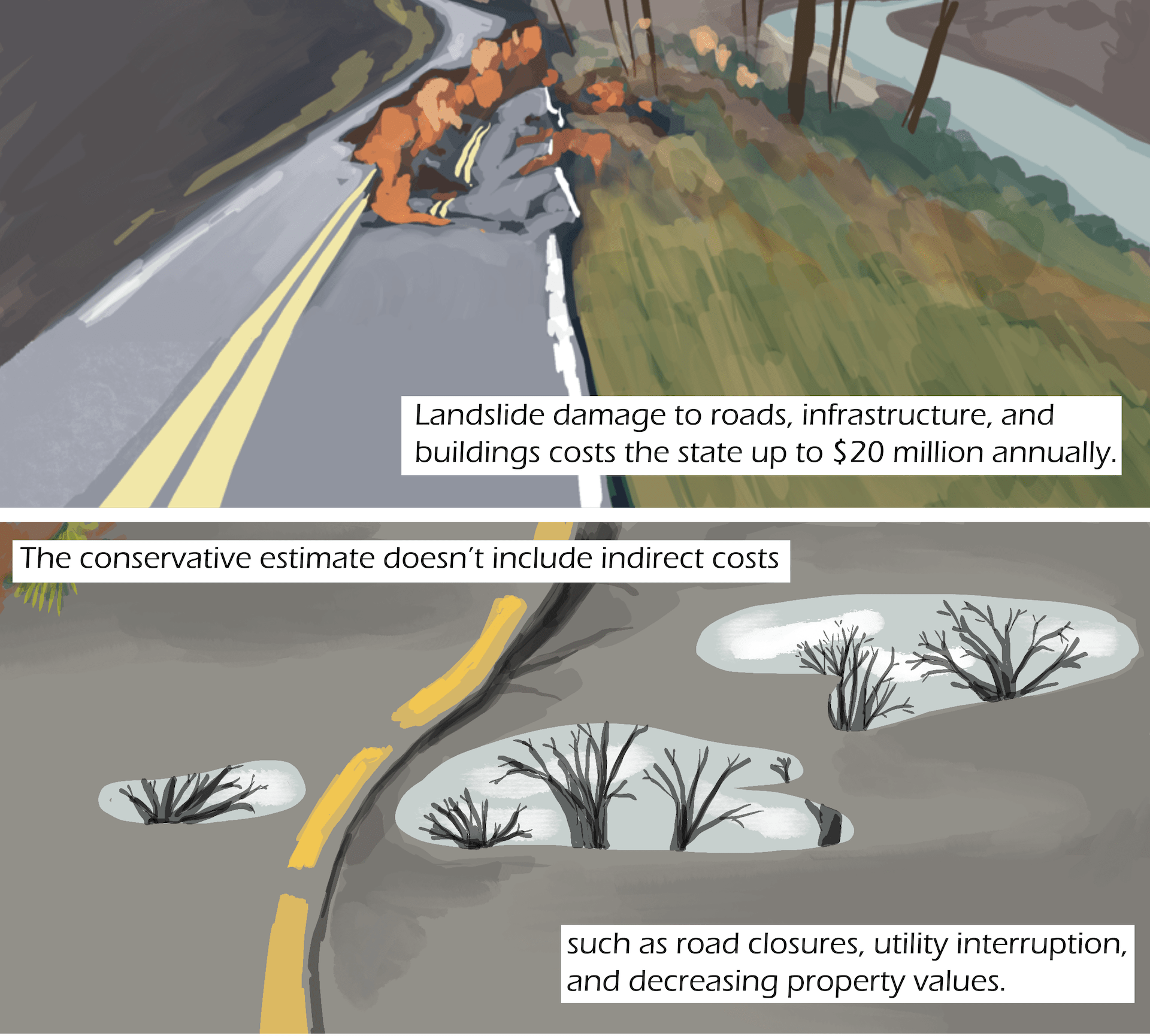

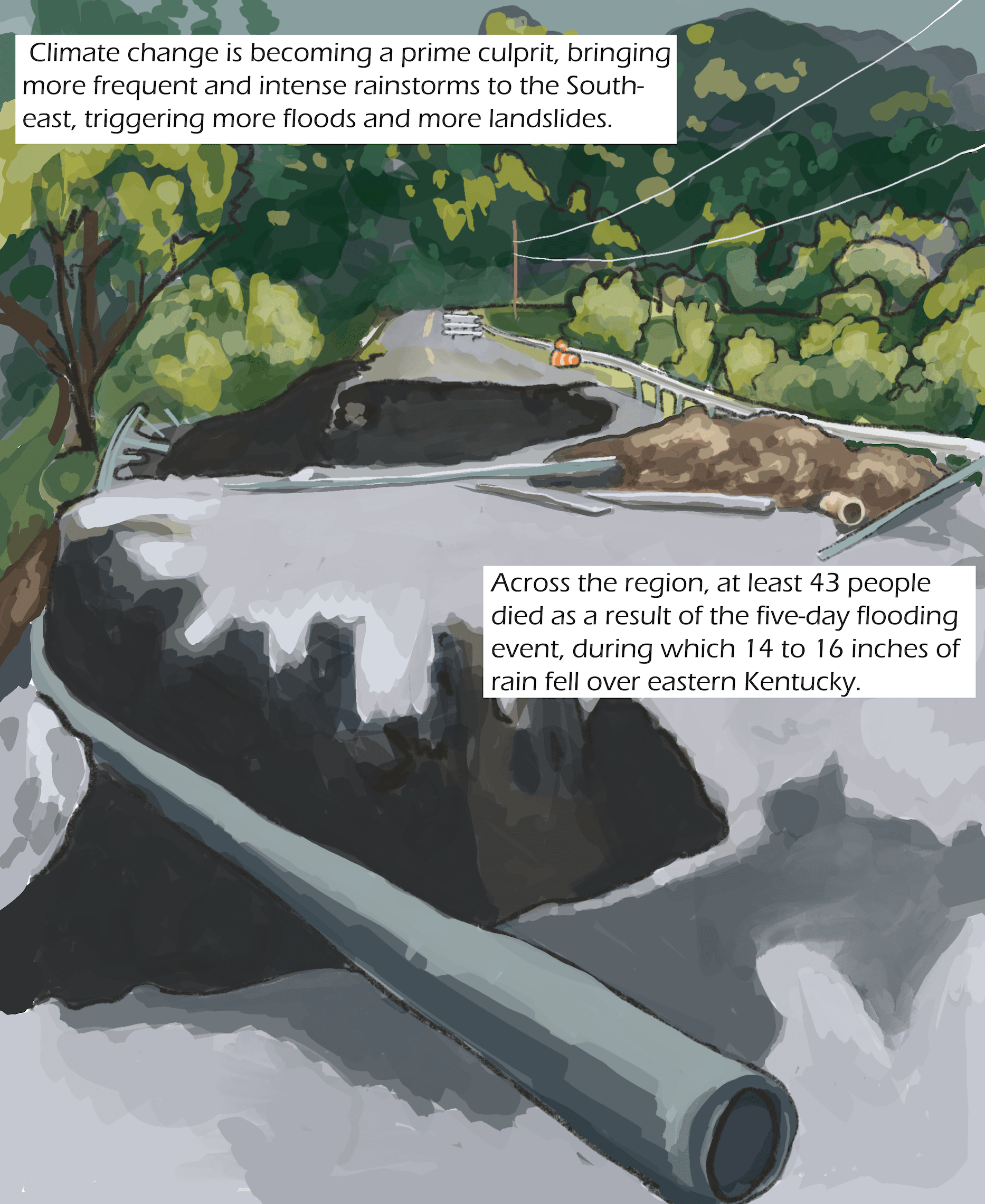

The narrow valleys and steep ridgelines of eastern Kentucky, dotted by private homes and businesses, are prime real estate for slips and slides. Landslide damage to roads, infrastructure, and buildings costs the state up to $20 million annually. The conservative estimate doesn’t include indirect costs such as road closures, utility interruption, and decreasing property values. Climate change is becoming a prime culprit, bringing more frequent and intense rainstorms to the Southeast, triggering more floods and more landslides.

Across the region, at least 43 people died as a result of the five-day flooding event, during which 14 to 16 inches of rain fell over eastern Kentucky. “We’ve had a lot more rainfall in the last seven years than I’ve seen in my lifetime,” said Matthew Wireman, judge executive for Magoffin County, near Perry County, where the Bakers live. “It’s like the Amazon rainforest up here.”

Some of the hardest-hit areas saw more than 10 inches of rain during the 24-hour period from July 27 to July 28, when the Bakers’ slide occurred. By November, the region had received more than $160 million in federal grants, loans, and flood insurance. But the Bakers, who’d almost lost their home for a second time in two years, would see very little of that assistance.

Transcript

Because standard homeowners insurance doesn’t cover “earth movement” — mudslides, mudflows, floods, earthquakes, or landslides — the Bakers’ insurance agent, State Farm, denied the family coverage in 2021 and 2022.

While mudflows and floods can be covered through the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Flood Insurance Program, insurance for mudslides and landslides remains elusive. The only way to insure against landslides is through a little-known policy called “Difference in Conditions,” sold by a surplus line insurer and typically purchased by business owners.

Bill Haneberg, Kentucky’s state geologist and director of the Kentucky Geological Survey, said one of the problems with landslide insurance is the function of all insurance: It’s communal. Car insurance works because a bunch of safe drivers have to buy it, funding the payout when unsafe drivers have a wreck. For landslide insurance to work, it would need to be sold to a lot of people who are very unlikely to see a landslide impact their home or business.

“The likelihood of an insurance product that’s meaningful for people living in landslide-prone areas is in the distant future,” said Jeff Keaton, geologist at the environmental consulting firm WSP USA.

In theory, landslides could be insured like earthquakes, a separate hazard insurance that exists because engineers created earthquake-resistant structures and building codes. But there is no basis for measuring the performance of buildings exposed to landslides, so insurers can’t forecast losses.

“If you give me a ZIP code, in a couple mouse clicks I can tell you the level of earthquake hazard,” Keaton said. “We need that for landslides.”

![Three images: a man with a moustache in panels one and three, in panel two an outline of the state of Kentucky. Text: Counties also struggle to fund repairs. In December, Matthew Wireman, the Magoffin County judge executive, was pinching pennies to make payroll after trying to fix four years’ worth of landslides: A 2021 study found more than 1,000 landslides in Magoffin alone, a county with the highest unemployment rate in the state. Matthew Wireman: “I’d just like to see the funding [for landslides] a lot quicker. Taxpayers are having to pay for all of this upfront, and it’s a burden on our citizens.”](https://grist.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/4.4-45-min-e1677799710602.png)

Transcript

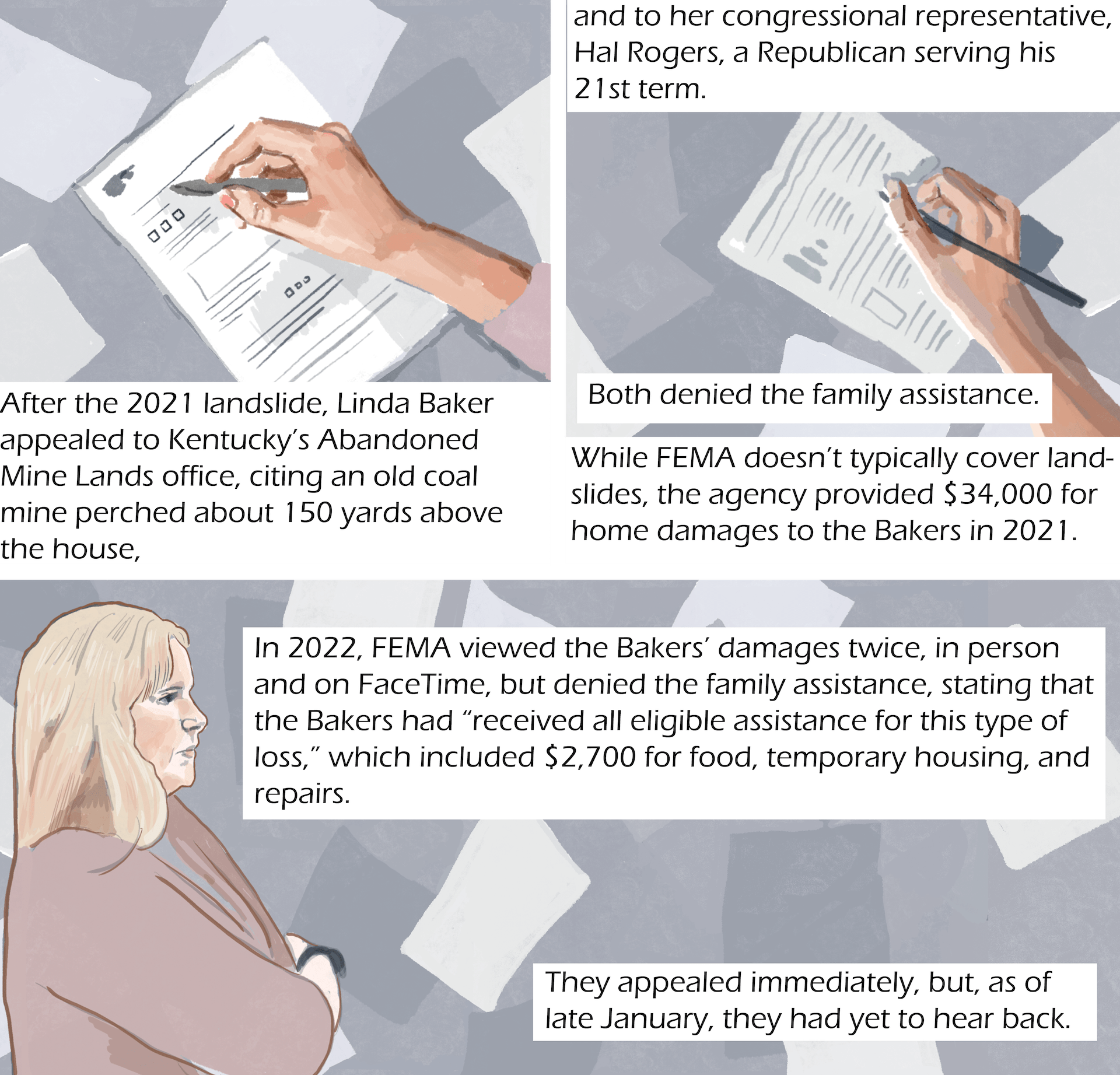

After the 2021 landslide, Linda Baker appealed to Kentucky’s Abandoned Mine Lands office, citing an old coal mine perched about 150 yards above the house, and to her congressional representative, Hal Rogers, a Republican serving his 21st term. Both denied the family assistance. While FEMA doesn’t typically cover landslides, the agency provided $34,000 for home damages to the Bakers in 2021.

In 2022, FEMA viewed the Bakers’ damages twice, in person and on FaceTime, but denied the family assistance, stating that the Bakers had “received all eligible assistance for this type of loss,” which included $2,700 for food, temporary housing, and repairs.

They appealed immediately, but, as of late January, they had yet to hear back.

The last option for the Bakers is Small Business Administration loans. In 2021, they borrowed roughly $69,000 and took out a second mortgage. In 2022, they borrowed $25,000, narrowly avoiding a third mortgage. They’d bought their house just three years earlier for $136,000. Today, the loans have nearly eclipsed their mortgage.

Counties also struggle to fund repairs. In December, Matthew Wireman, the Magoffin County judge executive, was pinching pennies to make payroll after trying to fix four years’ worth of landslides:

A 2021 study found more than 1,000 landslides in Magoffin alone, a county with the highest unemployment rate in the state.

“I’d just like to see the funding [for landslides] a lot quicker,” Wireman said. “Taxpayers are having to pay for all of this upfront, and it’s a burden on our citizens.”

Hoping to ease the burden, the Kentucky Geological Survey began mapping landslides across the eastern half of the state. New data — free, publicly available maps of landslide susceptibility across five counties — was released this summer, right after the July floods. Haneberg’s January report discovered 1,000 new landslides and debris flows in areas most affected by the July floods.

“We wanted to make sure that information was available, because we knew there’d be a lot of landslides,” Bill Haneberg said.

Transcript

Last summer, when the second landslide hit their house, the Bakers lived with relatives for more than 10 days. They lost electricity for a week, and water for two. Neighbors donated heavy equipment for the initial cleanup so they could re-enter their home.

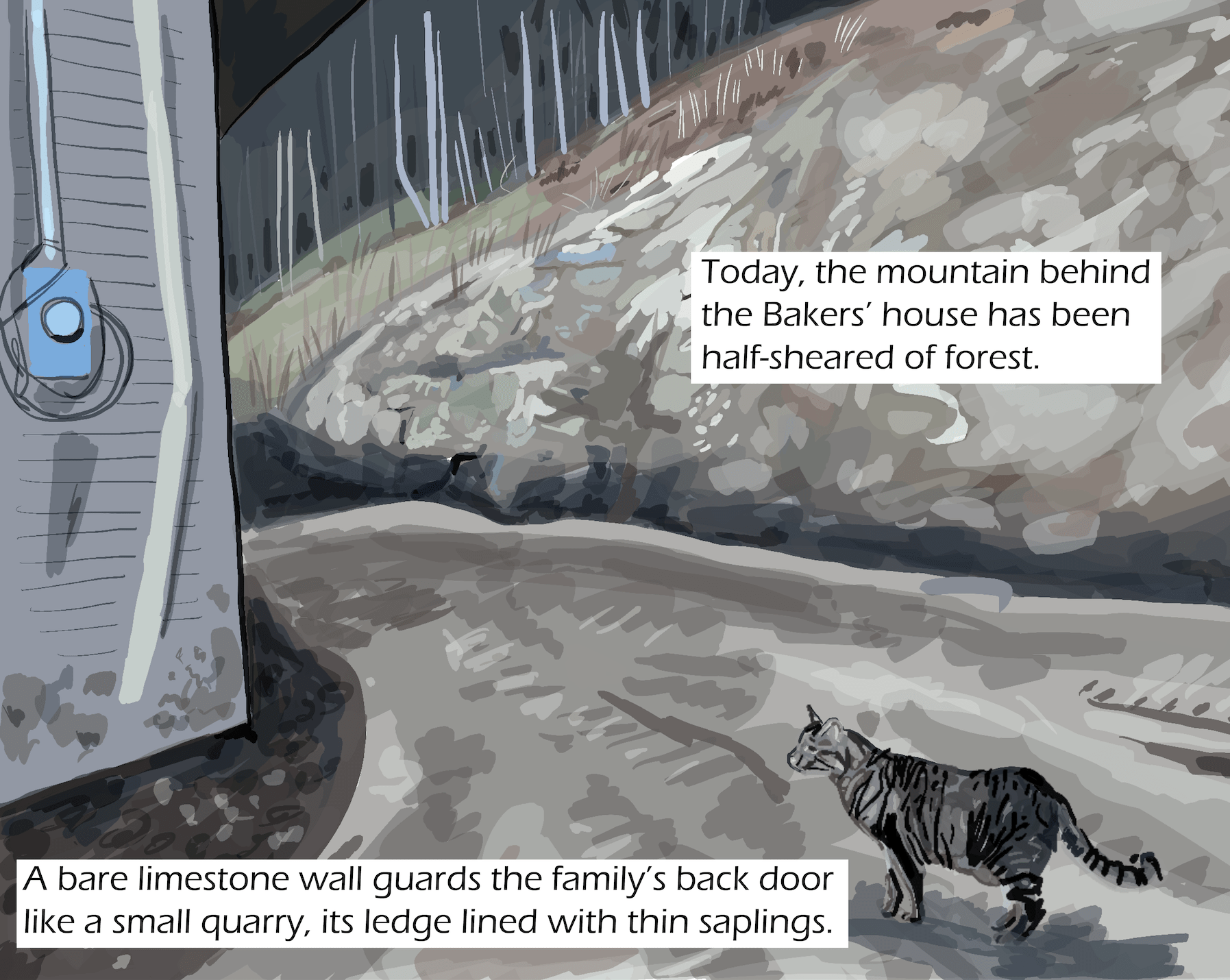

For weeks, plywood covered the window where Ian slept. The Small Business Administration told the Bakers it was swamped for requests for assistance. Today, the mountain behind the Bakers’ house has been half-sheared of forest. A bare limestone wall guards the family’s back door like a small quarry, its ledge lined with thin saplings.

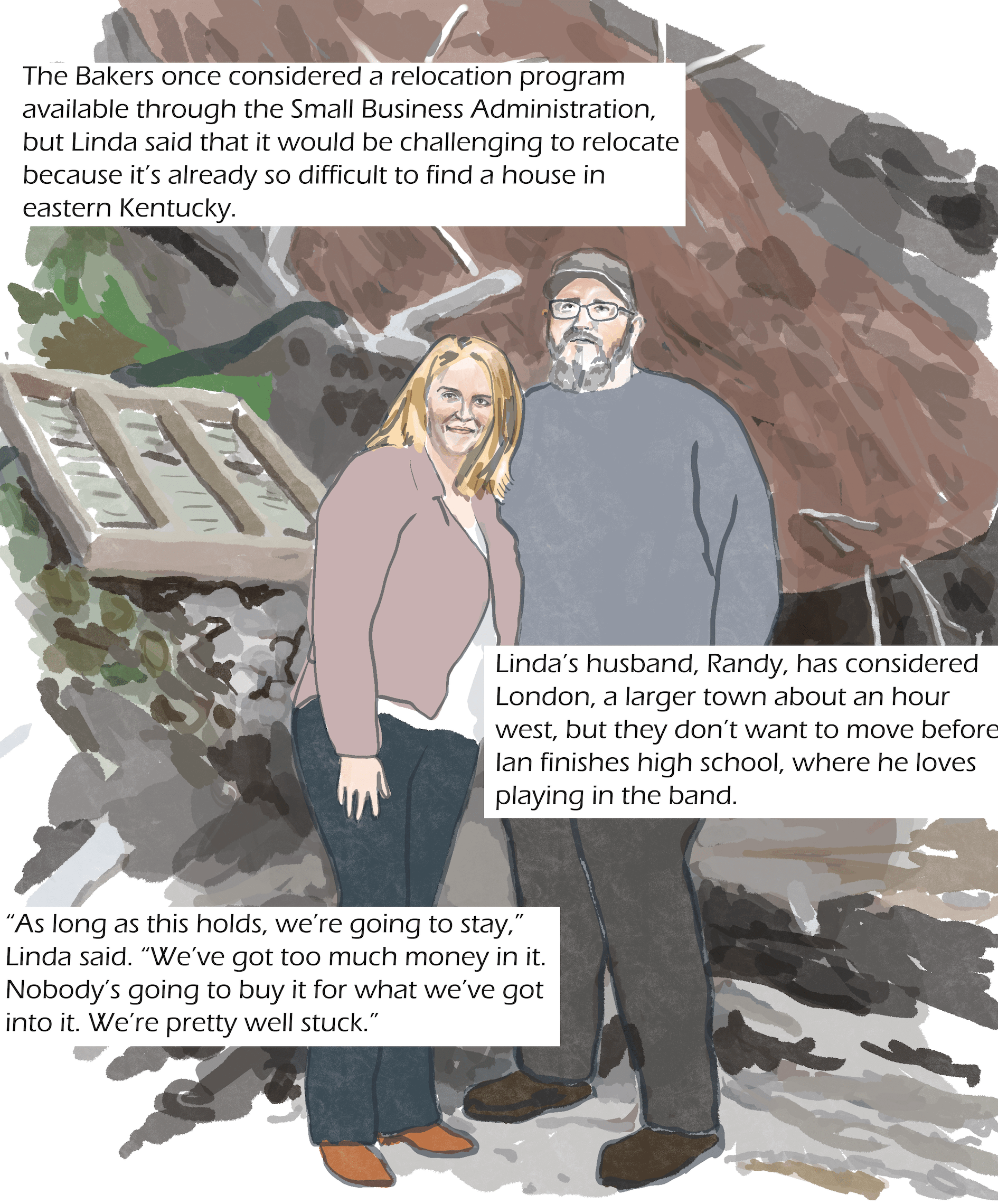

The Bakers once considered a relocation program available through the Small Business Administration, but Linda said that it would be challenging to relocate because it’s already so difficult to find a house in eastern Kentucky. Linda’s husband, Randy, has considered London, a larger town about an hour west, but they don’t want to move before Ian finishes high school, where he loves playing in the band.

“As long as this holds, we’re going to stay,” said Linda Baker. “We’ve got too much money in it. Nobody’s going to buy it for what we’ve got into it. We’re pretty well stuck.”