This story was originally published by ProPublica.

By the spring of 2020, the century-old industrial plant on Birmingham’s 35th Avenue was literally falling apart. Chunks of the metal doors fronting several of the 1,800-degree ovens — which heat coal to produce a fuel called coke — had broken off and tumbled to the ground.

With the doors damaged, the toxic chemicals they were supposed to contain within the ovens leaked out at an accelerated rate. The fumes should still have been captured by a giant ventilation hood that had been put in place to suck up emissions. But that system was broken, too, causing plumes of noxious smoke to drift across the city’s historically Black north side, as they had done so many times before.

Months earlier, a regulator with the Jefferson County Department of Health had sent a letter warning the plant’s owners that they could soon be cited for failing to prevent pollution from escaping from the ovens in different ways.

“It seems inevitable,” the letter said.

But in the months that followed, the company that had recently bought the plant told regulators it was unable to make millions of dollars worth of necessary repairs to the oven doors and ventilation hood, records, and interviews show. The delays carried a tremendous cost: Nearby residents were once again being exposed to dangerous levels of cancer-causing chemicals.

No Southern city has experienced a longer and more damaging legacy of environmental injustice than Birmingham. As coke production fueled the city’s rise — powering plants that made everything from cast-iron pipes to steel beams — white leaders enacted housing policies that forced Black people to live in the most hazardous communities. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once called Birmingham America’s “most thoroughly segregated city,” and the evidence of oppressive pollution was blatant. The air in north Birmingham residents’ lungs and the soil beneath their feet became more contaminated than in nearly any other corner of America.

Generations of business leaders amassed fortunes by cooking coke without regard to the pollution raining down on neighboring communities. With few exceptions, each plant owner left the facility in worse shape than they found it, passing off costly upgrades to the subsequent owner, who then passed them on to the next. This pattern was able to continue, in part, because powerful industry lobbyists fended off the kind of proposals and policies that better protected communities in other states. Nowhere was that more apparent than at one of the country’s worst-polluting plants, on 35th Avenue in Birmingham.

It was here, in an area with one of America’s highest poverty rates, that the ultrawealthy owners of a coal company named Bluestone Coke spotted a financial opportunity. Bluestone belongs to the family of Jim Justice, the coal baron who became West Virginia governor in 2017. The Justices had racked up tens of millions of dollars in unpaid bills with smaller companies it did business with, according to a ProPublica investigation in 2020. (Forbes dubbed Governor Justice the “deadbeat billionaire” because of these debts.) After a close business associate suddenly had to offload his Birmingham coke plant in 2019, the Justices bought the decrepit facility, which would prove to be a ready-made customer for the coal their company mined in several Appalachian states.

The Justices, like the owners of other remaining coke plants, sought to preserve the plant’s last years of revenues at a time when steel mill owners around the country were replacing coke-fueled furnaces with cleaner electric ones. To do so, they would cut corners on maintenance on creaky ovens, even though that would dramatically heighten the odds of increased pollution.

In July 2020, after the 35th Avenue plant was found to have released excessive levels of toxic emissions on most days that year, Jefferson County inspectors cited Bluestone for a series of violations. The health department was considering a fine of nearly $600,000, a penalty that’s small compared to fines that regulators in other states have issued for similar infractions but large by Jefferson County’s standards. In fact, it would have exceeded the fines issued to all Birmingham-area industrial sources over the previous decade. Instead of finalizing a settlement that would’ve fined Bluestone, though, Jefferson County scrapped it.

Over the course of the next year, Bluestone committed so many more infractions that it could have owed maximum penalties exceeding $60 million, according to legal filings. The violations got so bad that in August 2021, nearly two years after Jefferson County had warned that citations would be “inevitable,” the health department denied Bluestone’s request to renew the site’s permit. The Jefferson County Board of Health sued the company for damages, alleging that its operations were “a menace to the public health.”

Bluestone appealed the decision to deny its permit renewal and was initially able to stay open, releasing toxic chemicals into the surrounding communities well into the fall. But repeated problems with its equipment forced Bluestone to idle its coke ovens last October. Only then did it promise to make the major repairs needed to renew its permit.

ProPublica has learned that the Jefferson County Board of Health and Bluestone recently entered talks to settle the lawsuit. If Bluestone makes overdue repairs to its pollution control equipment and pays a penalty of $850,000 — less than 2 percent of the maximum possible fine — the company will be able to apply to renew its permit, according to sources who did not want to be named because the settlement is still being negotiated. If the head of the Jefferson County Department of Health approves the permit, Bluestone can resume its production of tens of thousands of pounds of coke each year.

Jordan Damron, a press secretary for Governor Justice, did not respond to ProPublica’s request for comment. Bluestone attorney Robert Fowler, who declined to answer ProPublica’s questions, wrote in an email that the company is committed to “achieving compliance with all local, state, and federal environmental laws.” Bluestone said it has spent millions of dollars to improve the plant and told regulators that it has the funding to make additional repairs. Wanda Heard, a spokesperson for the health department and the health board, declined to answer most questions for this story. Jason Howanitz, a senior air pollution control engineer for the department, said in a statement that he and his colleagues “work with residents and industry to ensure violations are handled swiftly and effectively to prevent violations from escalating.”

The chronic problems with the plant have spurred Birmingham Mayor Randall Woodfin to draft an unprecedented and as-yet-unfunded plan to buy out and relocate hundreds of neighboring residents. But launching the effort could take years — unless industrial companies like Bluestone, and the agencies tasked with regulating such plants, help to right the historic wrongs that plague the city’s north side.

“Bluestone hasn’t been a responsible operator,” Woodfin told ProPublica. “They’ve been blatant. They’ve been disrespectful. Bluestone doesn’t give a damn about people.”

On a recent summer afternoon, Lamar Mabry stepped past colorful toys strewn across the living room floor and went into his backyard. He pointed toward the far end of the nearly 1-acre lot containing several homes belonging to his family, at the five-bedroom brick house where he had grown up, just 600 feet from Bluestone’s front gates. From the front yard there, he could see the plant’s smokestack. As the years passed, pollution from the plant stained the house’s white facade a dark charcoal.

Since the late 1970s, Mabry has been complaining about the pollution from the coke plant and other sites clustered around his historic Black community of Collegeville. The 71-year-old contractor built his current house on the family land, and he and his late wife raised their younger children there. He now helps out with his grandchildren, who visit him often.

The neighborhood where Mabry once played in the streets and where his family gardened vegetables is now filled with abandoned homes and vacant lots. When the plant was running, the smell of pungent chemicals often killed his appetite and at times made him feel dizzy. In a legal filing before the Bluestone plant idled, Mabry said that the toxic emissions from the coke ovens left him “depressed” because his grandkids couldn’t “go outdoors during the summer months because of the pollution.”

He also worries his yard is too contaminated for his grandchildren to safely dig in the dirt. The EPA believes dirt that was given away by local industrial companies in the mid-20th century was spread by residents throughout their neighborhoods — and often contained toxic chemicals. Mabry’s older brother, Charles, who had worked at the 35th Avenue coke plant, brought truckloads of that dirt home to level their yard. Mabry said that in the early 2010s, the EPA sampled his soil but only tested the edges of his yard and didn’t find enough pollutants there to excavate it and replace it with clean soil. (The EPA excavated the yards of both of his neighbors, as well as hundreds of other nearby properties.)

Still, no matter how much pollution fell from the sky or lay beneath his feet, Collegeville had always been home. So for a long time, Mabry clung to the idea that he would die in the only community where he’s ever lived, even after he heard more neighbors’ stories of children with asthma and seniors with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. As the years passed, though, seven of his 14 siblings were diagnosed with cancer. “I’ve got a lot of death certificates,” he said. Enough, in fact, that he recently and reluctantly began to weigh the idea of moving, in hopes of finding a safer place for his grandchildren, all under the age of 14.

“My five grandkids, that’s my whole pride and joy,” Mabry said. But it’s still not an easy decision. “It will hurt me. All my memories are here.”

Mabry and other residents of Birmingham’s north side are worried that if Bluestone is allowed to resume operations at the plant, the government officials who had promised to protect them before will fail to do so again. It is a pattern they knew all too well, a pattern as old as the city itself.

The decade after the Civil War ended, a Confederate colonel named James Withers Sloss created a business empire in Birmingham on his belief that nearby coal deposits were vast enough to revive the region. Like many of his contemporaries, he built his companies on a system of racist labor practices. He invested in mines that shipped coal to Sloss Furnaces downtown, where freed Black people worked the city’s most dangerous ironworking jobs for the lowest pay. In 1883, Sloss told lawmakers that he relegated Black people to those positions because they had more of “a fondness for” that kind of work than white people did. Historian W. David Lewis later wrote that Sloss and other post-Civil War industrialists had turned Birmingham into “an iron plantation in an urban setting.”

When Sloss cashed out by selling his flagship iron furnace for $2 million — more than $60 million in today’s dollars — the investors who bought it relied on forced labor. They paid sheriffs to lease prisoners — many of them descendants of formerly enslaved Black people who were facing trumped-up charges by white people — to mine coal to pay off their fines.

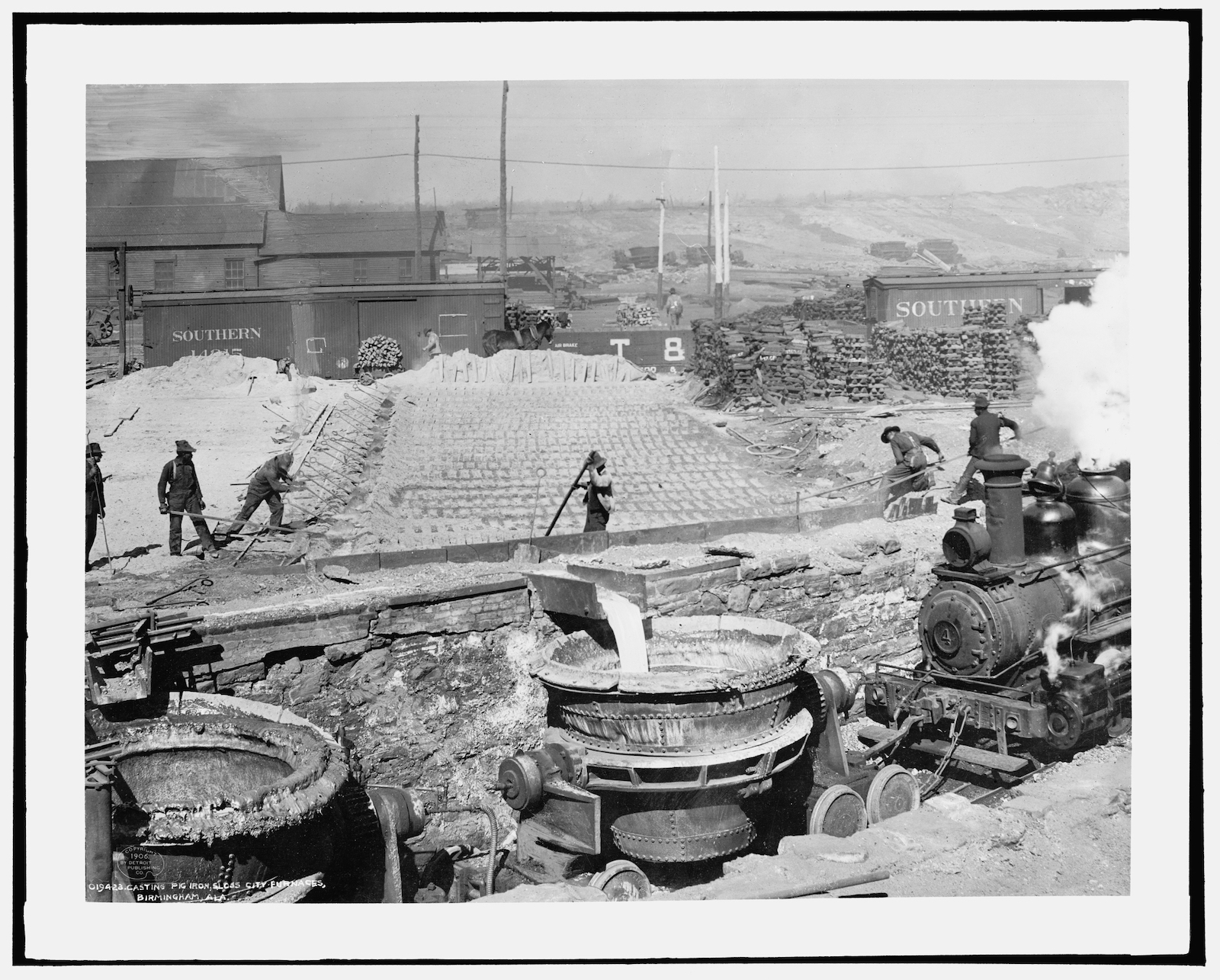

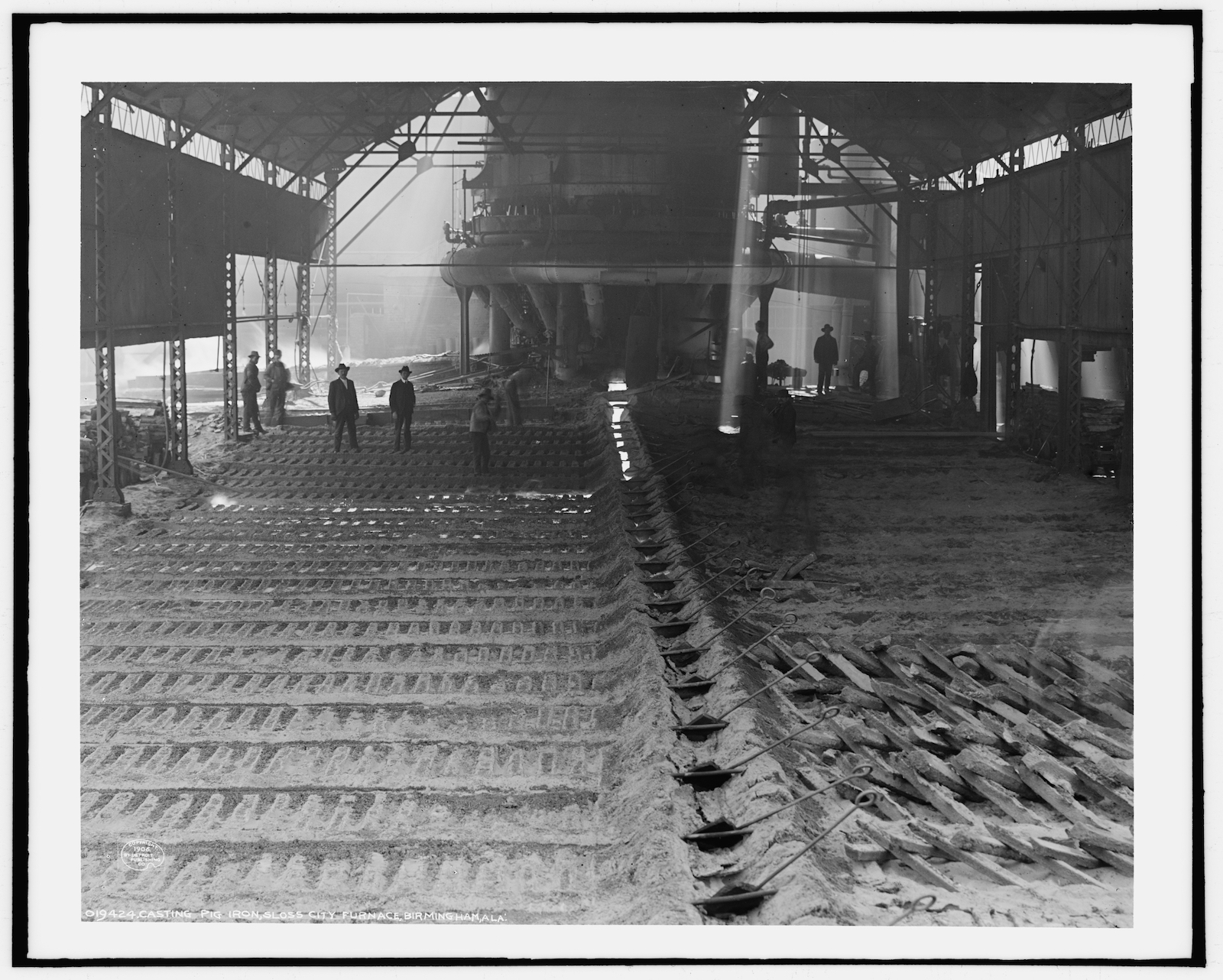

Sloss Furnaces, Birmingham, 1906. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The investors boosted production so much that by the early 20th century the amount of iron forged in Alabama surpassed that of Pennsylvania. To honor Birmingham’s rise, civic boosters paid the Sloss-Sheffield Steel & Iron Company to supply iron for a 56-foot-tall statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and forge, that would stand atop nearby Red Mountain. But in the valley below, Birmingham was heavily obscured by smoke from the growing number of iron and steel mills.

In 1913, city commissioners banned companies from firing up their plants more than three minutes an hour. But after a Sloss-Sheffield executive was arrested for defying the ordinance, local industrialists pressured the commissioners into weakening the restriction and convinced state lawmakers to strip the city of its power to limit industrial pollution. Sloss-Sheffield’s lobbying later helped the company land a military contract so large that it decided to build a new coke plant on 35th Avenue.

Though Alabama would end convict leasing in 1928 — abolishing the practice once exploited by Sloss-Sheffield — Black employees worked in fear of white foremen. “They called you a n—– and you did what they told you to do,” a Sloss-Sheffield worker from the 1920s to the 1940s later said in an oral history interview. “It would make you angry and you’d fret over it but you did it anyway because you didn’t have a choice.”

The year after World War II ended, a 22-year-old dockworker named John Powe came home from overseas and headed to Birmingham to find a job that would support his growing family. Like many rural Black southerners, Powe’s search for opportunity beyond tenant farming — the work his father had done in rural central Alabama — drew him to the industrial mecca, which had grown sevenfold since the turn of the century to more than 260,000 people. After briefly working for another company, he followed his older brother to Sloss-Sheffield.

Working as a laborer at Sloss was “rough,” Powe recounted in his own oral history interview, conducted in 1984. “When I first came out there I stayed on the job for 36 hours.” He added: “I feel lucky to be able to walk around.” Each shift presented potential dangers, from the risk of explosions to toxic chemicals. After a decade on the job, Powe lost a portion of his foot in a workplace accident.

By the 1940s, pollution from Sloss-Sheffield facilities and dozens of other plants across Birmingham was becoming hard for some city officials to ignore. Federal aviation officials blocked funding to expand the city’s airport because of excess smoke and dust, and medical leaders refused to build a tuberculosis hospital in Birmingham. In response, Sloss-Sheffield vowed to lower emissions. But those voluntary efforts failed to protect workers, who were found to have “high disease and death rates,” according to a 1946 report published by health officials in Jefferson County.

Redlining and the city’s racial zoning law prohibited Black people from moving into white neighborhoods. Powe — along with three of his brothers, who each worked for Sloss-Sheffield — moved to one of the few places he could: a short walk from the coke plant, in the tightknit neighborhood of Collegeville. His oldest son, John Henry Powe, remembers his dad coming home from work in the 1950s covered in soot from head to toe and handing his dirty work clothes to his wife, Ruby, who washed out the chemical stains by hand. The particles also landed on neighbors’ cars, leaving a fine layer of soot that covered the hoods like pollen in the spring.

Julia Powe, one of Powe’s nieces, remembers other, more direct threats to her family, beyond those posed by the coke plants. She felt her house rattle after terrorists bombed the nearby home of Bethel Baptist Church Pastor Fred Shuttlesworth, who organized civil rights demonstrations at his sanctuary. Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor — a notorious public safety commissioner with close ties to the Ku Klux Klan — ordered the arrest of hundreds of Black children, including Powe’s daughter, Queen, during a protest to end segregation.

While Black residents fought to desegregate the city, many white families moved “over the mountain,” to suburbs with safer air. Researchers found that remaining Birmingham residents were exposed to so many pollutants — such as cancer-causing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons — that breathing the air was equivalent to smoking two and a half packs of cigarettes a day. From the early 1960s to the early 1970s, the Birmingham area saw emphysema death rates spike by 200 percent, so bad that one federal official declared Birmingham’s air quality to be the worst in the South.

For years, Julia Powe said, her mother wanted to move away from the city’s north side because of its toxic air. But there was nowhere they could afford to go.

“We made do with what we had,” Powe said. “We had to go along to get along.”

By the fall of 1971, Birmingham’s pollution had triggered a full-blown public health crisis. Skyscrapers disappeared behind a hazy blanket of smog. As Marvin Gaye’s environmental anthem “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” was broadcast over radios nationwide (“Where did all the blue skies go? / Poison is the wind that blows”), editors at the Birmingham Post-Herald printed a front-page “pollution count” tracker that told families like the Powes and the Mabrys how much toxic air they would breathe.

Jefferson County officials, stripped of their powers by the state, could only request that plant owners slash emissions. Alabama Governor George Wallace — best known for proclaiming “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” in response to public school desegregation — delayed naming anyone to a state commission that was supposed to decide how to meet standards set by the Clean Air Act of 1970. That federal law empowered the newly created EPA to improve air quality nationwide.

After Birmingham companies continued to ignore requests that they voluntarily reduce emissions, Jefferson County officials persuaded the EPA to ask a federal judge to shut down 23 industrial sites. The judge agreed, lifting the hazy blanket from the skyline. In the weeks ahead, Wallace’s appointees finally met, and they soon created new pollution regulations.

Over the next five years, the quality of Birmingham’s air dramatically improved. But a pocket of toxic emissions stubbornly remained along the city’s north side, in part because of the coke ovens so close to Mabry’s and Powe’s homes.

The thick black smoke that drifted into communities not only contained particulate matter that made it harder to breathe, but also carcinogenic pollutants invisible to the human eye. By the late 1970s, the EPA concluded that “little doubt is left” regarding the cancer risk of emissions from the 60 coke plants then operating in the U.S. Yet each successive presidential administration, facing pressure from steel execs concerned about rising costs, refrained from using its power to protect communities against those emissions. In the mid-1980s, President Ronald Reagan withheld funding for regulators to curb coke plant emissions. In 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed into law an overhaul of the Clean Air Act that mandated stronger emissions controls but granted coke plants three decades to meet the full requirements of the tougher law. And in the final week of President Bill Clinton’s term in 2001, the EPA loosened controls on pollution from coke plants.

“Coke ovens became a classic example of a very old technology that was never forced to modernize,” said Jane Williams, chair of the Sierra Club’s National Clear Air Team, who advises communities impacted by coke oven emissions.

By the early 2000s, the EPA acknowledged in a report to Congress that federal regulations alone wouldn’t stop toxic air pollution in Birmingham and other cities considered America’s worst hot spots. A top EPA official informed Jefferson County regulators that their department had lax coke ovens emission standards that fell short of those in other states. But nothing happened. (Howanitz, a Jefferson County regulator, said in a statement that the EPA’s summary of the county’s standards was an “oversimplification” that “does not accurately reflect the rules of Jefferson County.”)

Birmingham’s northern cluster of aging industrial plants, along with the disinvestment and blight accelerated by the pollution they emitted, had spurred an exodus. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Collegeville’s population shrank from 7,000 to under 4,200 residents. Though Powe and his brothers would spend their golden years in Collegeville, most of their children, including John Henry and Julia, moved elsewhere.

“The businesses moved out, then the people moved out,” said John Henry Powe, who relocated 10 miles northeast to the suburb of Center Point. “People wanted better.”

Residents like Mabry who chose to stay soon learned of another pollution threat. In 2005, the company that then operated the 35th Avenue plant, Sloss Industries Corporation, discovered the presence of cancer-causing contaminants in soil sampled in adjacent neighborhoods. The discovery came on the heels of a 16-year EPA-mandated investigation to determine the extent to which dozens of contaminants had leached out of disposal pits on the roughly 400-acre coke plant site.

It took another four years for the EPA to ask Sloss Industries’ successor, Walter Coke, to sample soil near additional homes and schools. That testing found concerning levels of toxic contaminants, including arsenic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, at roughly two dozen of those sites. The EPA quickly informed school officials that contaminants had elevated cancer risk above what the environmental agency deems acceptable.

Walter Coke voluntarily dispatched bulldozers to several schools to remove the toxic dirt and replaced it with clean soil. But company execs hoped to limit their additional cleanup costs. Chuck Stewart, Walter Coke’s president, told the EPA that assigning blame to his plant alone was “profoundly misleading.” He argued that contamination came from “multiple sources” in a part of town where more than 75 plants had operated since the late 19th century. Given the legacy of the industrial corridor, he urged EPA officials in 2011 to get other companies “to the table to discuss any cleanup.”

Around that time, the EPA declared portions of neighborhoods around the 35th Avenue plant a Superfund site, which allowed the agency to spend millions of dollars to clean up the hazardous pollution. In 2013, the EPA named four more companies — including Walter’s top rival, Drummond — as “potentially responsible” for the remediation costs. Soon after, EPA officials sought to add the area to its National Priorities List, a designation that allows the agency to pool more resources that can accelerate such cleanups.

Fearing a $100 million cleanup bill, Drummond’s vice president convinced Democratic state representative Oliver Robinson to fight the NPL designation. After thousands of dollars were secretly funneled to his foundation by a nonprofit run by the Drummond vice president, Robinson hired a friend to get northside residents to sign a petition expressing concern that being placed on the NPL would lower their property values. A lawyer working with Drummond’s vice president used information collected by Robinson to draft talking points, which Republican officials used to publicly oppose the NPL designation.

The tidal wave of backlash they fomented was successful. The EPA dropped the NPL effort in 2015. EPA spokesperson Brandi Jenkins said in a statement that the agency’s “decisions regarding cleanups are not influenced by lobbying interests.”

Robinson later pleaded guilty to federal corruption charges related to his campaign against the NPL effort. The Drummond vice president was convicted for his role. Hank Asbill, a lawyer representing the Drummond vice president, said in an email that his client “did not get a fair trial and was wrongly convicted.” A lawyer for Robinson did not respond to a request for comment. Drummond representatives also did not respond to a request for comment.

That winter, EPA contractors excavated the soil around a red brick house owned by lifelong Collegeville resident Jimmy Smith. The 82-year-old had worked for U.S. Pipe, which had once owned the 35th Avenue coke plant, for more than four decades. The EPA’s excavation followed its discovery of unsafe levels of arsenic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Smith’s front yard. After that, he became convinced that the polluted air and soil had caused the cancer that afflicted his family. His mother died from lung cancer, and he lost his oldest daughter to multiple cancers.

It was all but impossible for Smith to know the extent to which the cancer-causing chemicals had contributed to his family members’ illnesses, though federal health officials say that long-term exposure to such chemicals increases cancer risk. By the time a backhoe arrived to dig up the toxic soil, Smith thought, it was time to go.

“Once we realized the severity of the pollution, what it was doing to us, what it had been doing to us, we moved out of there,” Smith said.

Six months after EPA contractors excavated Smith’s yard, Walter Coke’s parent company filed for bankruptcy. When a company called ERP Compliant Coke acquired the 35th Avenue plant the following winter, 33-year-old environmentalist Michael Hansen felt what he called a “twinkle of hope.” Hansen, whose nonprofit the Greater-Birmingham Alliance to Stop Pollution had urged the health department to address residents’ concerns about pollution, believed the plant’s change in ownership could signal a new era. ERP’s owner, Tom Clarke, had vowed to plant millions of trees on old industrial sites he’d bought elsewhere to offset their carbon footprints. Hansen had also heard a rumor that Clarke might decommission the plant and convert the property into a land trust to restore it.

However, as Hansen drove through Collegeville in the ensuing months, he could smell the scent of burning rubber and mothballs, telltale signs of coke oven emissions. The sight of plumes of smoke became so common that GASP staffers sent complaints to the health department. But Jefferson County regulators said they never found enough evidence of violations to fine ERP. The plant kept polluting under ERP’s ownership until Clarke ran into financial trouble. In 2018, he missed a loan payment for another of his properties. Following that, his bankers called the full note due immediately. Clarke, who once volunteered to help the Justices confront their long list of mining violations, sold the Birmingham plant to Bluestone. (Clarke and his attorney did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

As the Justices folded the Birmingham plant into their business empire’s future plans, they slashed the costs of running the site. In January 2020, Bluestone laid off dozens of employees, leaving the plant with fewer than 100 workers, according to their union president. Yet once COVID-19 swept the nation, the company applied for PPP loans, claiming that it would protect the jobs of more than 150 people. ProPublica’s PPP loan database shows that federal officials approved $4.6 million in loans and eventually forgave the full amount. Fowler, the Bluestone attorney, declined to comment.

The plant’s purchasing manager, meanwhile, said in a deposition that he was told to ask 50 contractors if they would accept reduced payments for services they had already performed. Everyone from coke oven part makers to fire extinguisher distributors sued Bluestone to get their full payments. (As of July, ProPublica had found that judges had ordered Bluestone to pay in nine lawsuits and had dismissed nine others. It’s unclear how many of the dismissals occurred due to settlements. Eight cases were still ongoing.) Bluestone even delayed payments to contract inspectors who compiled emissions data for the Jefferson County Department of Health.

“It takes an incredible amount of maintenance to keep one of these plants running,” said Erik Groth, an environmental specialist who said Bluestone owes him more than $10,000 for emissions monitoring. “When essential services started disappearing, like toilet paper in the bathrooms, I prepared for the worst.”

Hansen, for his part, was alarmed that Bluestone had not paid the taxes needed to get a business license. If the family wouldn’t take care of the most basic of operational obligations, Hansen reasoned, the company was unlikely to invest in fixing the problems that led to the health department violations.

Since Jefferson County was not regularly conducting toxic air monitoring, GASP collected samples of its own. Shortly after Bluestone arrived in Birmingham, Hansen’s group found evidence of two chemicals often released by coke plants, benzene and naphthalene, at levels that elevated cancer risk. In late 2020, GASP partnered with an expert to place air monitoring devices on church windows and at schools less than half a mile from the coke ovens. After three months collecting samples, Wilma Subra, a Louisiana-based environmental health expert who advises the EPA on community concerns, reviewed the results for GASP. She concluded benzene, naphthalene, and other toxic chemicals were present at levels high enough to have an “extensive and severe” impact on the health of nearby residents.

Following Jefferson County’s denial of Bluestone’s permit in August 2021, a leader with the economic development nonprofit Birmingham Business Alliance emailed health department regulators on Bluestone’s behalf to find a way to “resolve their problems regarding air quality.” The following month, Jay Justice — Governor Justice’s son, who is the head of Bluestone — reached out to one of Jefferson County’s top air pollution regulators to schedule an in-person meeting. He wrote that he was looking “to develop a pathway forward that can allow the plant to continue to operate, provide jobs, pay taxes, and be a great environmental steward while doing so,” according to an email obtained by ProPublica. (The health department’s Howanitz said that he and other air pollution regulators never met with BBA employees or Jay Justice because of the pending litigation. Neither the BBA nor Justice responded to multiple requests for comment.)

One week later, a Bluestone attorney named Alan Truitt stepped inside a courtroom in downtown Birmingham. Truitt, a seasoned defender of corporate polluters, urged the judge assigned to Bluestone’s appeal to give the company more time to repair the plant. Truitt had warned in an emergency filing that if the plant shuttered — even temporarily — it would be damaged beyond the point of repair. He pleaded for the judge to act in a way that would avoid the “permanent loss” of jobs for hard-working Alabamans.

The judge decided to let Bluestone stay open until the appeal was finished. Less than a month later, however, the company suspended production after most of the plant’s coke ovens had broken down.

When asked by a West Virginia TV reporter at a press conference last November about the violations leading up to the shutdown, Governor Justice shifted blame to previous owners, noting that the “plant had been bankrupt, for all practical purposes, bankrupt two different times prior to us getting it.”

Despite Governor Justice’s vow at the press conference “to do the right stuff,” his family was notorious for amassing huge debts that often went unpaid, according to lawsuits. Plaintiffs including miners and the U.S. Department of Justice have won judgments or forced settlements worth more than $128 million against the family’s companies, according to a 2020 ProPublica investigation. Mounting debts slowed the company’s progress to reopen the Birmingham plant. In the three years since the Justices bought the plant, vendors have sued Bluestone for more than $8 million over unpaid bills for equipment, utilities, and services provided.

This past May, at a hearing that concerned nearly $900,000 owed to the city for unpaid business license taxes and fees, Bluestone lawyer James Vercell Seal told the judge that the company is “doing a lot of infrastructure improvements” to get the plant running again. That same day, Seal told another judge that Bluestone was “unable to pay” its $1.8 million water bill because the plant was “not producing” any coke. This double standard frustrated vendors. “I feel like a bill collector,” a water utility attorney told the judge.

When word spread that the Jefferson County Board of Health might settle with Bluestone for less than $1 million, experts familiar with the coke plant’s operations struggled to understand why the penalty was so low. Stan Meiburg, a former EPA Acting Deputy Administrator who now runs Wake Forest University’s Center for Energy, Environment, and Sustainability, said the proposed $850,000 settlement is a “steep discount” from a maximum penalty that exceeds $60 million. (Howanitz said in a statement that the health department “does not comment on specific penalty calculations.”)

If the settlement is finalized, only a few options will remain to protect the people of north Birmingham, according to experts. The head of the Jefferson County Department of Health could deny Bluestone a permit if the company doesn’t fix enough of the problems with its pollution control equipment. If the department fails to do that, Meiburg said, the EPA could intervene by ordering the company to install toxic air monitoring and pay more fines to deter it from repeating its past violations.

Bluestone publicly declared it had spent “tens of millions of dollars” to make the plant “more compliant.” But experts say that figure is far too low: Rebuilding the 35th Avenue plant’s coke ovens, they say, could cost more than $150 million.

“Bluestone should never be given another permit,” said one coke plant expert familiar with the plant’s operations, who did not want to be named out of fear of retribution. “It’s bad for residents. It’s bad for workers. Nobody would win except for Bluestone.”

With each day that passes, the idea of moving away from Collegeville becomes easier for Mabry — but the act itself becomes more difficult. Repeated failures to control emissions from high-polluting plants have contributed to the decimation of his neighborhood’s property values. Homes in Collegeville have sold for as little as $1,000.

Mabry said the four-bedroom house he built with his own hands is worth much less than it should be, effectively trapping him there. That house, along with his childhood home and several other structures on the property, would cost about $350,000 to replace, according to his homeowners insurance policy. But when he recently got an appraisal on his property, it was valued at around $75,000.

Birmingham Mayor Woodfin, who has an ambitious plan to buy out property owners near the plant for a fair price, has seen signs of harm to these communities — Collegeville in particular — throughout his life. He attended elementary school less than a mile from the 35th Avenue plant and as a teenager lived at his aunt’s house, a short walk from Carver High School.

In 2018, during his first year as mayor, Woodfin toured part of the Superfund site near the old Carver High, where EPA officials in recent years have stored mounds of toxic dirt removed from people’s yards. After seeing the neighborhood remain in that condition for that long, Woodfin wanted to do more as mayor. He said his staff has since crafted a $37 million blueprint known as “The Big Ask” to address some of the damage to north Birmingham. The 60-page document, which has not yet been released to the public, calls for more than $19 million to pay for property buyouts within the Superfund site. Another portion would help renters, including those in Collegeville’s public housing complex, relocate. Millions of dollars more would be spent to revitalize the area for those who want to stay.

While Woodfin supports Birmingham funding part of The Big Ask, he believes the city should not pay for the buyouts alone. But no other government agencies have come to the table. Heard, the spokesperson for the Jefferson County Board of Health, wouldn’t say if it would devote the fines collected from a Bluestone settlement to help fund the proposal. The EPA said it doesn’t plan to help fund the relocation of residents. The agency pointed out that it has so far spent $45 million on the Superfund cleanup efforts and intends to spend up to $100 million total, covering the full cost of reducing health risks from contaminated soil. President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure bill is providing $3.5 billion to the EPA for accelerating cleanups at Superfund sites, but agency officials said much of the initial $1 billion installment is meant to clear the backlog of work at previously unfunded sites.

Woodfin said plant owners in north Birmingham should pay their fair share of The Big Ask. Corporations across the country, from Juliette, Georgia, to Murray Acres, New Mexico, have bought out residents after dangerous chemicals leaked out of waste sites. But the odds of Bluestone contributing are slim, considering that the company has told the EPA that it doesn’t even have the money to cover the cost of protecting residents from future harm by cleaning up the legacy waste of the 35th Avenue plant.

But even if Woodfin finds funding for The Big Ask, it only covers buyout offers for a third of the more than 2,100 properties in the Superfund site. When ProPublica pointed out that the plan excludes most property owners in Collegeville, Woodfin acknowledged that everyone in the Superfund site should be eligible. Unless the plan changes, Mabry, whose property is closer to the 35th Avenue plant than almost every other resident, will be left out.

Alex Mierjeski, Maya Miller, Ken Ward Jr. and Lylla Younes contributed reporting.