This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

The California water wars of the early twentieth century are summed up in a famous line from the 1974 film Chinatown: “Either you bring the water to L.A., or you bring L.A. to the water.” Nearly a hundred years have elapsed since the events the film dramatizes, but much of the West still approaches water the same way. If you don’t have enough of it, go find more.

As politicians across the West confront the consequences of the climate-fueled Millennium Drought, many of them are heeding the words of Chinatown and trying to bring in outside water through massive capital projects. There are at least half a dozen major water pipeline projects under consideration throughout the region, ranging from ambitious to outlandish. Arizona lawmakers want to build a pipeline from the Mississippi River more than a thousand miles away, a Colorado rancher wants to pipe water 300 miles across the Rockies, and Utah wants to pump even more water out of the already-depleted Lake Powell.

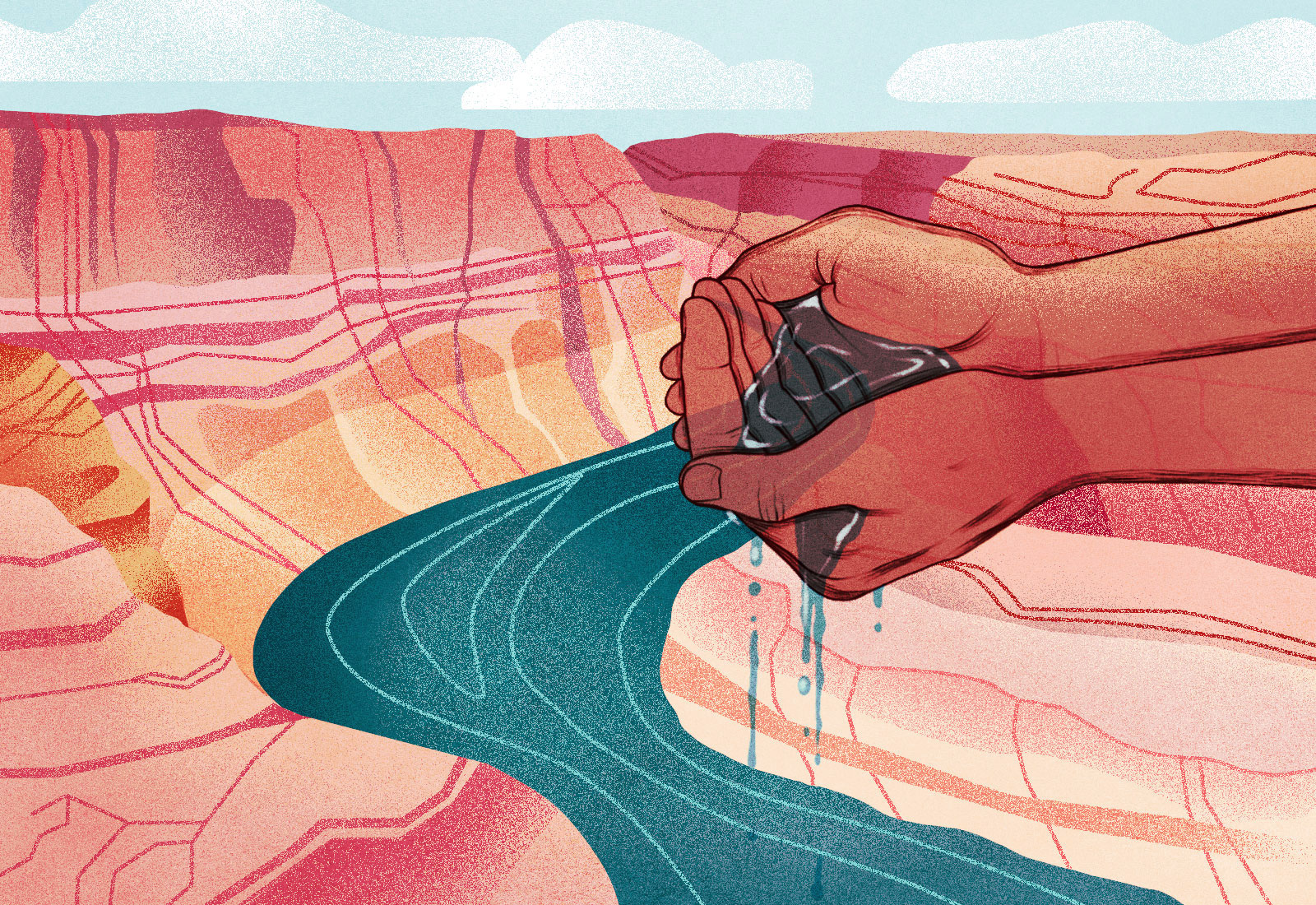

Proponents of these projects argue that they could stabilize western cities for decades to come, connecting populations with unclaimed water rights. Their detractors counter that, in an era of permanent aridification driven by climate change, the only sustainable solution is not to bring in more water, but to consume less of it. Either way, most of these projects stand little chance of becoming reality — they’re ideas from a bygone era, one that has more in common with the world of Chinatown than the parched west of the present.

As western states grew over the twentieth century, the federal government helped them build several massive water diversion projects that would hydrate their growing urban populations: The Central Arizona Project aqueduct brought water from the Colorado River to Phoenix, for instance, and the Big Thompson system piped water across the Colorado Rockies to Denver. Each state along the Colorado River basin had the rights to a certain quantity of river water, divided among major users like farms and cities, and the projects were designed to help the states realize those abstract rights.

“States have [historically] been very successful in getting the federal government to pay for wasteful, unsustainable, large water projects,” said Denise Fort, a professor emerita at the University of New Mexico who has studied water infrastructure.

It’s easy to understand why politicians want to throw their weight behind similar present-day projects, Fort told Grist, but projects of this size just aren’t practical anymore. For one, there’s no longer enough unclaimed water to make most pipeline projects cost-effective. Additionally, building large infrastructure projects in general has become more difficult, in part thanks to reforms like the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires that detailed environmental impact statements be produced and evaluated for large new infrastructure projects.

These realities haven’t stopped the West’s would-be water barons from dreaming. The hypothetical Mississippi River pipeline, which gained new life last year amid devastating drought conditions, is a case in point. The basic idea is to take water from the Mississippi River, pump it a thousand miles west, and dump it into the overtaxed Colorado River, which provides water for millions of Arizona residents but has reached historically low levels as its reservoirs dry up. The Arizona state legislature allocated seed money toward a study of a thousand-mile pipeline that would do exactly this last year, and the state’s top water official says he’s spoken to officials in Kansas about participating in the project. Meanwhile, a rookie Democrat running for governor in California’s recall election last year proposed declaring a state of emergency in order to build a similar project.

The most obvious problem with this proposal is its mind-boggling cost. A federal report from a decade ago pegged an optimistic cost estimate for a similar pipeline at $14 billion and said the project would take 30 years to build; a Colorado rancher who championed the idea around the same time, meanwhile, estimated its costs at $23 billion. The actual costs to build such a pipeline today would likely be orders of magnitude higher, thanks to inflation and inevitable construction snags. Even at its cheapest, the project would cost about twice as much per acre-foot of water delivered than other solutions like water conservation and reuse.

Even if the sticker price weren’t so prohibitive, there are other obstacles. The project would have to secure dozens of state and federal permits and clear an enormous federal environmental review; moving the water would also require the construction of several hundred megawatts of power generation. Plus, the federal report found the water would be of much lower quality than other western water sources.

Even if the government could clear these hurdles, the odds that Midwestern states would just let their water go are slim. A multi-state compact already prohibits any sale of water from the Great Lakes unless all bordering states agree to it, and it’s almost certain that Mississippi River states would pass laws restricting water diversions, or file lawsuits against western states, if the project went forward.

“If this gets any traction at all, people in the flyover states of the Missouri River basin probably will scream,” one water official told the New York Times when the project first received attention. A man from Minnesota wrote to the Palm Springs Desert Sun earlier this month and expressed similar sentiments, warning, “If California comes for Midwest water, we have plenty of dynamite.”

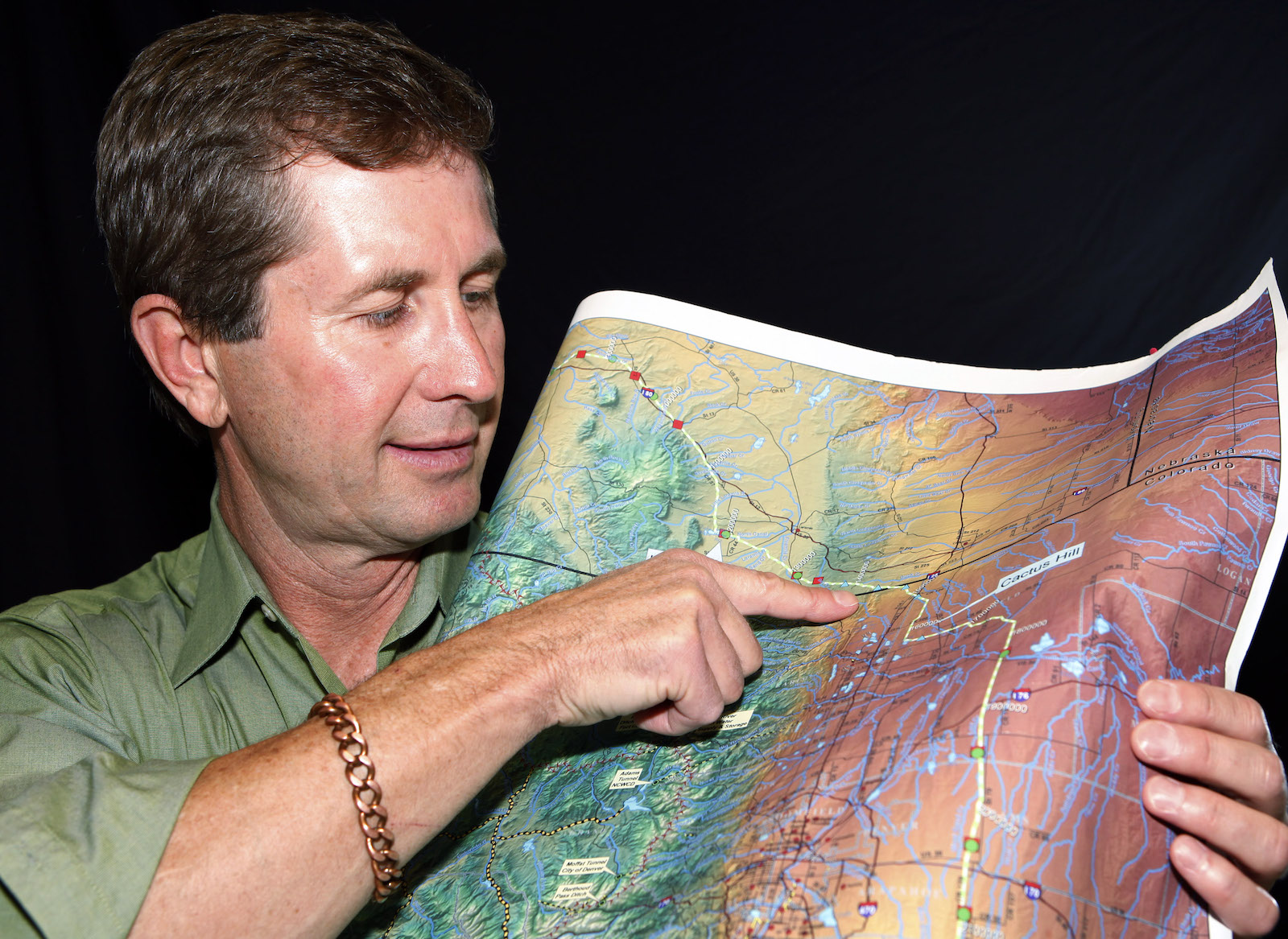

Even smaller projects stand to be derailed by similar hiccups. Take for instance the so-called Water Horse pipeline, a pet project of a Colorado investor and entrepreneur named Aaron Million. Almost two decades ago, when Million was working on a master’s thesis, he happened upon a map that showed the Green River making a brief detour into Colorado on its way through Utah. It dawned on Million that Colorado had unclaimed rights to water from the Green, since the river was part of the Colorado River system, and he devised a plan to build a pipeline that would pump water around the Rockies to the city of Fort Collins, where he lives. He frames the pipeline as a complement to water-saving policies.

“The state should do everything possible to push conservation, but that’s not going to cure the issue,” he told Grist. “Infrastructure is one of the few ways we’ll turn things around to assure that there’s some supply.”

In the 20 years since he first had the idea, Million has suffered a string of regulatory and legal defeats at the hands of state and federal agencies, becoming a kind of bogeyman for conservationists in the process. At one point, activists who opposed the project erected three large billboards warning about the high cost and potential consequences, such as the possibility that drawing down the Green River could harm the river’s fish populations. Nevertheless, Million hasn’t given up, and he’s currently working to secure permitting for the fourth iteration of the project.

This latest version would curve up through the Wyoming flatlands and back down to Fort Collins, a distance of around 340 miles. It would carry about 50,000 acre-feet of water per year, much less than the original pipeline plan but still twice Fort Collins’ current annual usage. Million told Grist that he’s secured partial funding for the project from multiple banks and the infrastructure company MasTec, but it remains unclear how much he would have to charge to make the project profitable. In any case, Utah rejected a permit for the project in 2020, saying it would jeopardize the state’s own water rights. Million sued, and he says he expects a ruling this year.

The list of projects that run on similarly magical thinking goes on: Utah wants to build a pipeline of its own from Lake Powell to the fast-growing city of St. George, but Lake Powell has almost no water left. Another businessman in New Mexico has pushed plans to pump river water 150 miles to the city of Santa Fe, but that water would have to be pumped uphill. California wants to build a $16 billion pipeline to draw water out of the Sacramento River Delta and down to the southern part of the state, but critics say the project would deprive Delta farmers of water and destroy local ecosystems.

Fort, the University of New Mexico professor, worries that the bigwigs who throw their energy behind large capital projects may be neglecting other, more practical options.

“The other alternatives have political costs, and they have costs that are maybe more likely to be borne locally,” including by farmers and other large water users, she said. “It’s much easier to [propose] a shining pipeline from the Mississippi River that will never be built than it is to grapple with this really unpleasant truth.”

Conservation alternatives are less palatable than big infrastructure projects, but they’re also more achievable. Arizona, for instance, has invested millions of dollars in wastewater recycling while other communities have paid to fix leaky pipes, making their water delivery systems more efficient. The elephant in the room, according to Fort, is agriculture, which accounts for more than 80 percent of water withdrawals from the Colorado River. If a portion of the farmers in the region were to change crops or fallow their fields, the freed-up water could sustain growing cities.

“There are no easy fixes to a West that has grown and has allocated all of its water — there’s no silver bullet,” she said. A water pipeline like Million’s would help, if he could wave a magic wand and build it, but Fort believes the present scramble over the Colorado River will likely make such projects impossible to realize.

Million himself, though, is confident that his pipeline will get built, and that it will ensure Fort Collins’ future.

“We’re not looking for the last dollar out of this project,” he told me. “We’re doing everything we can to minimize impacts, maximize benefits, and this project has a lot of benevolence associated with it.” In his vision of the West’s future, urban growth will necessitate more big infrastructure projects like his.

Still, he admits the road hasn’t always been easy, and that victory is far from guaranteed. “I’ve cowboyed enough in my life to know that you just got to stick to the trail,” he said. “We’ve had a few blizzards along the way, and some gun battles, but it is what it is.”