This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

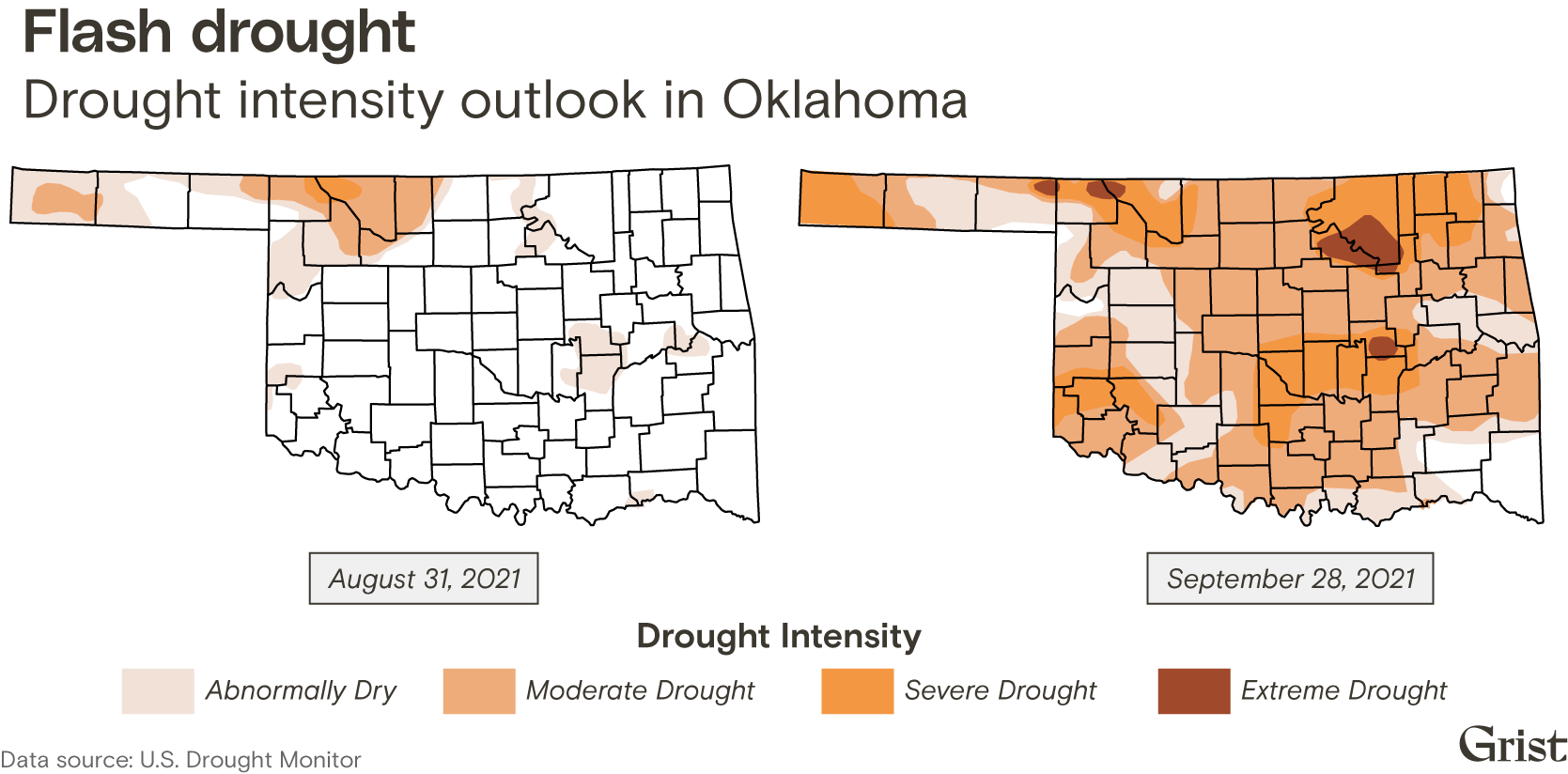

September in Oklahoma is typically a rainy season, when farmers take advantage of the state’s third-wettest month to plant winter wheat. But last year, many were caught off guard by abnormally dry weather that descended without warning. In the span of just three weeks, nearly three-quarters of the state began experiencing drought conditions, ranging from moderate to extreme.

Fast-moving droughts like this one are developing more and more quickly as climate change pushes temperatures to new extremes, recent research indicates — adding a new threat to the dangers of pests, flooding, and more long-term drought that farmers in the U.S. already face. Known as “flash droughts,” these dry periods can materialize in as quickly as five days, often devastating agricultural areas that aren’t prepared for them.

During last year’s drought in Oklahoma, Jonathan Conder, a meteorologist for a local news station in Oklahoma City, marveled at the speed and severity of the event. Tulsa, the state’s second-largest city, went 80 days without more than a quarter-inch of rain, while temperatures in southwestern Oklahoma climbed into the triple digits.

“This is huge for Oklahoma,” Conder said during his broadcast on October 1. “Our agricultural community, the farmers who plant wheat, they may not even be able to plant if they don’t get two inches of rain.”

The threshold for drought conditions differs by location, with the U.S. Drought Monitor using data on soil moisture, streamflow, and precipitation to categorize droughts by their severity. While typical droughts develop over months as precipitation gradually declines, flash droughts are characterized by a steep drop in rainfall, particularly during a season that normally receives plenty, along with high temperatures and fast winds that quickly dry out the soil. They can wither crops or prevent seeds from sprouting, delaying or diminishing the harvest.

Now, flash droughts are coming on faster and faster — making them more difficult to predict and more damaging, according to a recent study published in Nature Communications. The research, from scientists at the University of Texas and Hong Kong Polytechnic University, found that in the last 20 years, the percentage of flash droughts developing in under a week increased by more than 20 percent in the Central United States.

“There should be more attention paid to this phenomenon,” said Zong-Liang Yang, a geosciences professor at the University of Texas and one of the study’s co-authors, as well as “how to actually implement [these findings] into agricultural management.”

Scientists have long warned that warming temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns due to climate change pose a threat to the cash crops of the Midwest and Great Plains, primarily corn, wheat, and soybeans. But flash droughts are a relatively new area of research, Yang said, with the term gaining usage only in the last couple of decades.

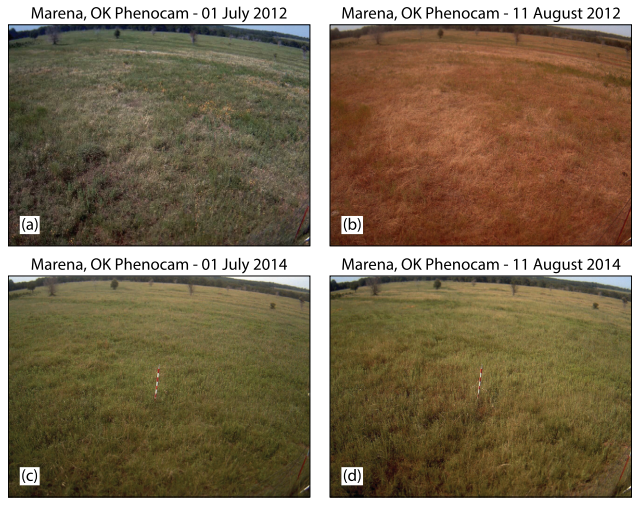

The increase in their severity and frequency, though, is already being felt across the U.S. In 2012, a flash drought struck the Central U.S. in the middle of the growing season, causing an estimated $31.2 billion in crop losses. Another flash drought hit Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota in the spring of 2017, leading to more than $2.6 billion in agricultural losses, along with “widespread wildfires, poor air quality, damaged ecosystems, and degraded mental health,” according to a study published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Flash droughts are also a global problem, with Brazil, India, and multiple countries in Africa facing the worst impacts. In 2010, a flash drought followed by a heatwave in Russia temporarily halted wheat exports, a major disruption for communities across the Middle East that depend on the country’s grain.

The damage flash droughts can cause depends on the crop and the time of year, said Dennis Todey, director of the Midwest Climate Hub for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Corn is the most vulnerable during its pollination season in mid-summer, while soybeans are affected in August and wheat during planting season in the spring.

Drought is a natural part of the climate in this region, Todey said, particularly in the western part of the Corn Belt — a region that encompasses the Midwest and the Great Plains. Many farmers have learned to adapt and integrate dry conditions into their planting cycles. But what makes flash droughts so dangerous is their rapid onset, Todey said, leaving little time for agricultural producers to prepare.

“Drought most times is thought of as a slow-starting and then a slow-stopping event,” Todey said. “In a flash drought setting … instead of just starting to dry out gradually, you have surfaces that dry out very quickly, you have some newly planted crops that are starting to be stressed more quickly.”

Many farmers don’t know if they’re starting to experience a drought, though, until expected rains fail to appear. Rainfall in mid-October helped ease the flash drought that began in Oklahoma in September, but after that a much longer drought set in, said Keeff Felty, a fourth-generation wheat and cotton farmer in the southwestern part of the state. As a result, some of his crop never germinated, while his overall yield dropped when it came time for the harvest.

“There’s a lot of information out there, and you have to avail yourself of what works best for you, but you also have to be prepared for it to go totally south,” Felty said. “Nobody saw [the drought] coming, and it’s just a fact of the weather that we don’t have any control over it. It’s just life.”

Typical droughts can last months or even years — the western U.S. is currently experiencing its third decade of “megadrought” — while flash droughts can end more quickly, within weeks or months, Yang said. And they can hit in relatively wet areas, including the eastern part of the country, where drought conditions are much more rare than in the West.

The main reason they’re occurring faster, Yang said, is climate change. As the air warms, it can lead to more evaporation and dry out the soil. This can occur even in areas that can expect to receive more rainfall overall because of climate change, because scientists project that rainfall will be unevenly distributed — falling in more extreme events and making other parts of the year drier.

“Every [recent] decade we have seen is the warmest decade in history,” Yang said. And with the world on track to blow past a global temperature that’s 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than the pre-industrial average, he expects to see both flash droughts and longer droughts occurring more frequently.

Researchers are working on improving their models to better predict flash droughts, Yang said, with the help of new technologies such as more granular satellite monitoring and machine learning. The main marker they look for is high rates of evapotranspiration, when plants suck up water from the soil and then release it into the air through their leaves — a process that accelerates with high temperatures and winds and can be monitored with special cameras that detect fluorescence, or the heat emitted by plants.

If farmers can know when to anticipate a flash drought, Todey said, they can skip or delay planting, or reduce their fertilizer usage when they know a crop won’t grow. They can also adjust their planting schedule and take better care of their soil by minimizing tillage, which dries it out even more. But with less and less time to prepare for flash droughts, Todey said, some may have to make difficult choices about whether to plant at all.

“Agricultural producers naturally adapt to changing conditions,” Todey said. “But eventually there comes a point where [losses] become more frequent. People start going, ‘Okay, this isn’t working.’”