Despite all the dire warnings, corporate pledges, and tree-planting promises, forests keep falling at an alarming pace. In a report out Wednesday morning, experts tallied up all the acres of the most important forests lost in 2020 and found that it amounts to an area the size of the Netherlands.

“Those dense forests can be hundreds of years old and store significant amounts of carbon. Losing them has irreversible impacts on biodiversity and climate change,” said Rod Taylor, director of the forest program at the nonprofit World Resources Institute, which produced the report with Global Forest Watch. The two organizations have been monitoring the world’s forests for 20 years with satellite images.

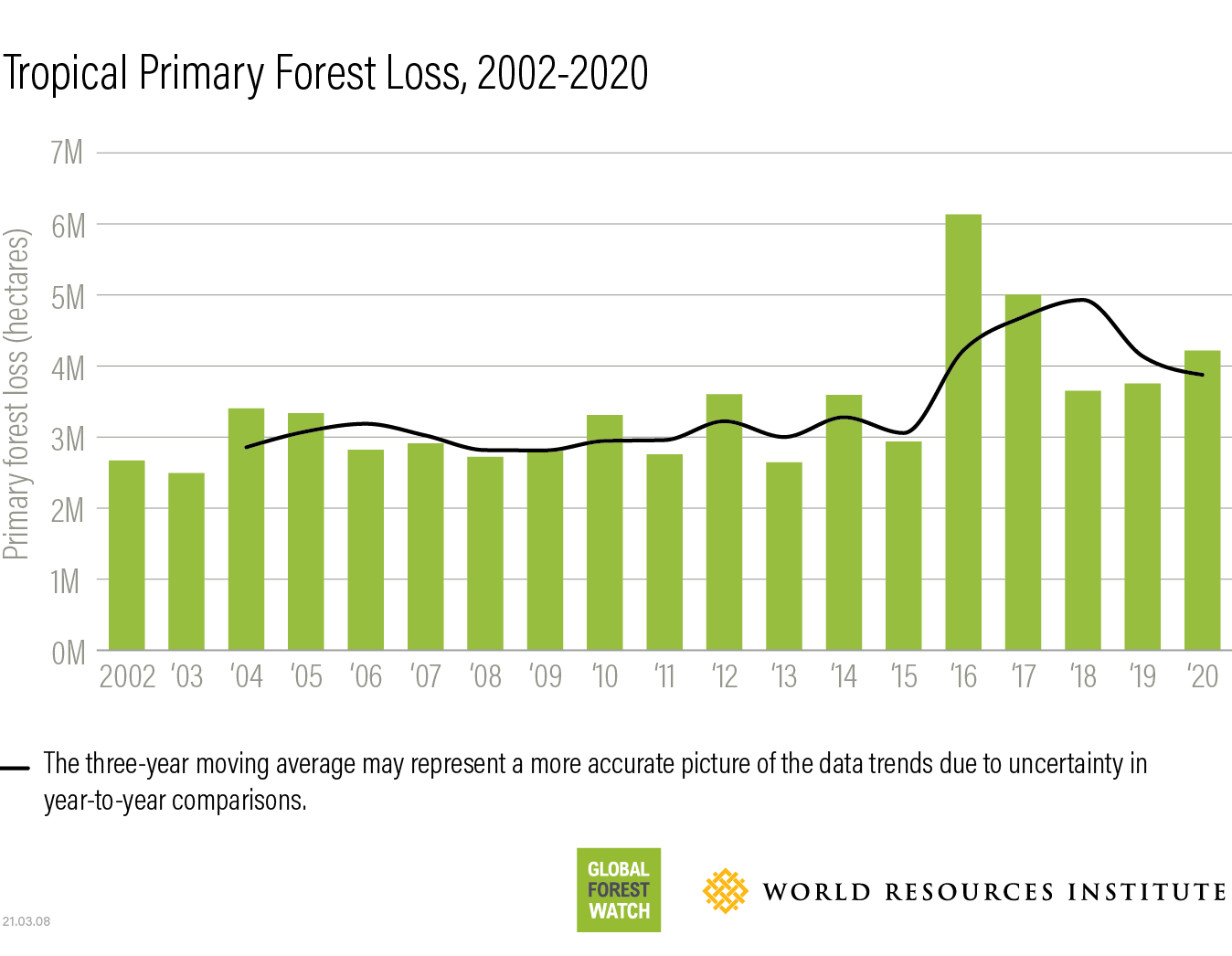

These tropical old-growth forests that WRI focused on don’t go through regular cycles of harvesting and regeneration, like those managed by timber companies. In a better world, the 4.2 million hectares of primary tropical forest that fell this year would have remained standing forever. Levelling them resulted in the release of some 2.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide, according to the report, equivalent to twice the annual emissions from automobiles in the United States.

Weather has become a driving force in forest loss. In places where weather was abnormally hot and dry last year, like Australia, Brazil, Bolivia, Germany, and Russia, forest fires flared and tree-cover loss spiked. The swampy Pantanal region in west-central Brazil lost nearly a third of its tree cover after a drought. In contrast, the numbers improved in Canada and Indonesia, where the weather was cooler and wetter.

It’s clear that forests are growing more vulnerable to severe weather as the climate warms, said Francis Seymour, an WRI fellow. “I mean wetlands are burning!” she exclaimed. “Nature has been whispering this risk to us for a long time, but now she is shouting.”

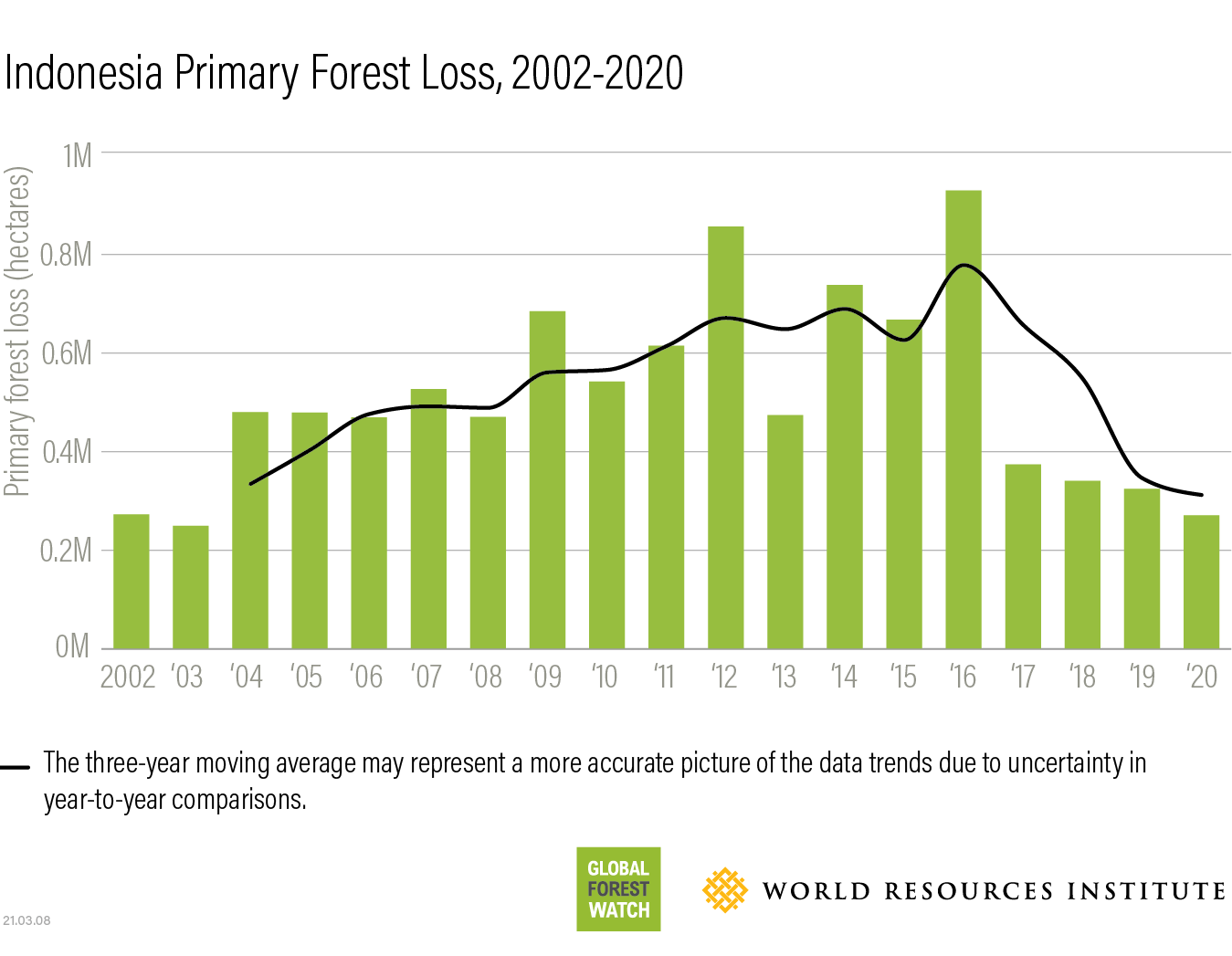

But there was some cause for hope: Indonesia, which has been among the top three deforesters for the previous 19 years, dropped into fourth place in 2020. That’s after four years of declining tree-cover loss.

Indonesia had good luck with the weather, with unusually heavy rains last year. Falling prices for palm oil during the pandemic relieved economic pressure to clear forests for palm plantations. But some of the credit should also go to the government, which took decisive action after devastating fires in 2016 and 2017 to squelch deforestation, Seymour said.

Cargill, the Singapore-based Wilmar International, and other big corporations involved in the palm oil trade have promised to freeze out plantations that bulldoze forests, but there are still bad actors. Palm oil prices have rebounded this year, which might make it tough for them to keep their promises. “I think this year and the next two to three years will be a real test to see if Indonesia can maintain its performance in reducing deforestation,” said Andika Putraditama, sustainable commodities and business manager, at WRI Indonesia.

In Africa last year, deforestation seemed to be primarily driven by small-scale farmers moving from one spot to the next rather than big corporations with big plantations. Trees are falling to farmers just growing food to feed their families, or woodcutters harvesting fuel for cooking. So in central Africa, keeping trees upright requires improving agriculture practices, rather than restricting farming. People have been expanding into forests because they don’t have the basic resources, like fertilizer, to keep renewing existing farmland, said Elie Hakizumwami, WRI’s country manager for the Democratic Republic of Congo.