Last year, Beluga Shipping discovered that there’s money in global warming.

Beluga is a German firm that specializes in “super heavy lift” transport. Its vessels are equipped with massive cranes, allowing it to load and unload massive objects, like multi-ton propeller blades for wind turbines. It is an enormously expensive business, but last summer, Beluga executives hit upon an interesting way to save money: Shipping freight over a melting Arctic.

Beluga had received contracts to send materials on a sprawling trip that would begin in Ulsan, South Korea, head north and west to the Russian port city of Archangelsk—located near the border with Finland—and wind up in Nigeria. Normally, this route requires Beluga’s ships to navigatea 11,000-mile route through the Suez Canal. But in 2008, executives for Beluga Shipping decided that global warming had eroded the Arctic’s summer sea ice significantly enough that their ships could travel the Northeast Passage [PDF] along the north coast of Russia. Previously,a cargo ship could only safely navigate that route if an icebreaker went ahead, smashing a route through thick ice.

Now, a warming climate had—for six to eight weeks beginning in July—transformed much of the route into mostly open water, studded with ice floes that the Beluga ships could navigate. So its executives got permission from the Russian government to travel along the coast, paid a transit fee of “a comparably moderate five-digit figure,” and sent the ships on their way. Four months later, they’d finished the trip. Compared to the old Suez Canal journey, this shorter route saved an enormous pile of money: It cost $300,000 less per ship in lower fuel and bunker costs. Global warming had boosted the company’s revenues by more than half a million dollars in one year alone.

Now, a warming climate had—for six to eight weeks beginning in July—transformed much of the route into mostly open water, studded with ice floes that the Beluga ships could navigate. So its executives got permission from the Russian government to travel along the coast, paid a transit fee of “a comparably moderate five-digit figure,” and sent the ships on their way. Four months later, they’d finished the trip. Compared to the old Suez Canal journey, this shorter route saved an enormous pile of money: It cost $300,000 less per ship in lower fuel and bunker costs. Global warming had boosted the company’s revenues by more than half a million dollars in one year alone.

When I interviewed Beluga CEO Niels Stolberg via email this spring, he said he envisions using the Northeast Passage regularly. Indeed, he’s planning on another trip this summer. He said that since the shorter passage requires generating far less C02, it’s “greener”; it’s also more ironic, since it was high concentrations of C02 that helped melt the route in the first place.

“I am convinced,” Stolberg added, “that the Arctic will become an area of quite regular sea traffic at least during summer.”

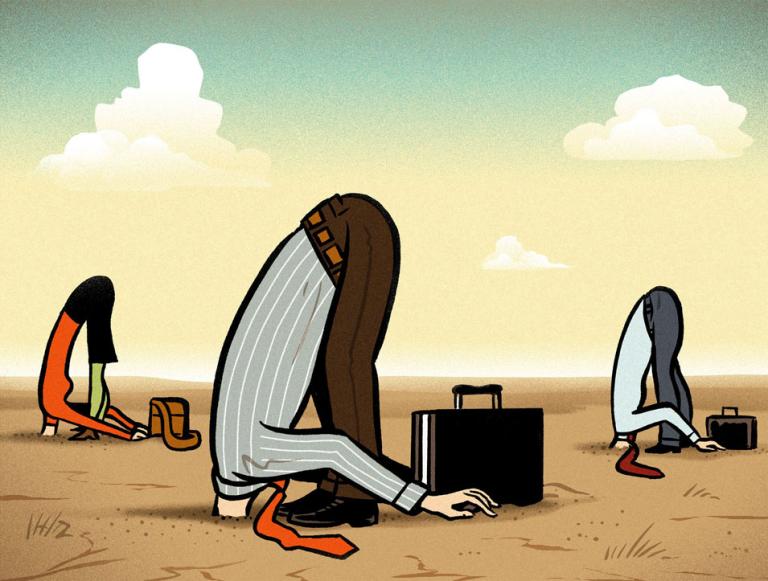

If you looked merely at the realm of politics, it would be easy to believe that the question “Is climate change really happening?” is still unresolved. In recent months, skeptics have attacked climate science with renewed vigor. Doubters seized on “Climategate“—leaked emails from bickering atmospheric scientists—to argue that the evidence in favor of warming is being cooked. Other skeptics unearthed shoddy parts of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s main report, such as the fact that it cited non-peer-reviewed work by an activist group when it predicted that the Himalayan glaciers would melt by 2035. And all along, conservative politicians have hissingly denounced global warming as a shady liberal scheme: Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma has famously called it “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people.” These attacks appear to be working. A spring Gallup study found that Americans’ concern over global warming peaked two years ago, and has steadily declined since.

But there’s one area where doubt hasn’t grown—and where, indeed, people are more and more certain that climate change is not only real, but imminent: The world of industry and commerce.

Companies, of course, exist to make money. That’s often what makes them seem so rapacious. But their primal greed also plants them inevitably in the “reality-based community.” If a firm’s bottom line is going to be affected by a changing climate—say, when its supply chains dry up because of drought, or its real estate gets swamped by sea-level rise—then it doesn’t particularly matter whether or not the executives want to believe in climate change. Railing at scientists for massaging tree-ring statistics won’t stop the globe from warming if the globe is actually, you know, warming. The same applies in reverse, as the folks at Beluga Shipping adroitly realized: If there are serious bucks to be made from the changing climate, then the free market is almost certainly going to jump at it.

This makes capitalism a curiously bracing mechanism for cutting through ideological haze and manufactured doubt. Politicians or pundits can distort or cherry-pick climate science any way they want to try and gain temporary influence with the public. But any serious industrialist who’s facing “climate exposure”—as it’s now called by money managers—cannot afford to engage in that sort of self-delusion. Spend a couple of hours wandering through the websites of various industrial associations—aluminum manufacturers, real-estate agents, wineries, agribusinesses, take your pick—and you’ll find straightforward statements about the grim reality of climate change that wouldn’t seem out of place coming from Greenpeace. Last year Wall Street analysts issued 214 reports assessing the potential risks and opportunities that will come out of a warming world. One by McKinsey & Co. argued that climate change will shake up industries with the same force that mobile phones reshaped communications.

Consider, as one colorful example, the skiing industry. Beginning ten years ago, the Aspen Skiing Company began noticing that European ski lodges were being slowly destroyed by warmer weather. Europe’s ski resorts tend to be located on lower mountains—about 6,000-8,000 feet high, compared to American peaks up around 11,000 feet—so they’re vulnerable to even extremely tiny increases in global temperature. The 2 percent rise in the 20th century was enough “to put a lot of them out of business,” says Auden Schendler, executive director of sustainability for the Aspen Skiing Company, which operates two resorts spread across four mountains.

But now Aspen’s own season is getting shorter: “More balmy Novembers, more rainy Marches,” Schendler says. “That’s what we’re seeing, and that’s what the science suggests would happen. If you graph frost-free days, there are more and more in the last 30 years.” Climate-change models also predict warmer nights. Aspen Skiing has noticed that happening too, and the problem here is that nighttime is when ski lodges use their water-spraying technology to make snow—”and if you make it when it’s warmer it’s exponentially more expensive.” The increasing volatility of weather overall—another prediction of climate change—poses a particular danger for ski resorts, because they operate in the red most of the year, making up their deficit during the ultra busy spring break in March. So if the weather is terrific for the entire winter but suddenly balmy during March break, that can ruin the whole fiscal year.

Schendler has also learned firsthand a point that climate scientists have been making for some time: With climate change, “warming” isn’t the only—or even the most serious—challenge. The sheer interdependence of complex ecosystems systems can grease you. For example, recent droughts in Utah have kicked up red dust clouds that settle on Aspen’s snow. This makes the snow melt more quickly (because the red absorbs more heat from the sun) while also making it too gritty to ski on.

Are all Aspen Skiing’s recent weather problems caused by global warming? It’s impossible to tell. But as Schendler notes, the last few years certainly mimic the precise effects that climate models predict, so it is at least a taste of what’s to come. During a recent dust storm on Aspen’s slopes, Schendler’s boss wandered into his office looking morose. “He said, ‘Auden, if climate change is the scary thing for the future, this is the apocalypse now. What if you get this in March?”’ Schendler recalls.

Now, all this tricky weather hasn’t exactly destroyed Aspen Skiing; the firm could probably survive even worse stuff. The top of the mountain is so high “we can ski it in 50 years and it’ll be great,” Schendler notes. But it could certainly erode Aspen’s profits, and Colorado would suffer: The ski industry overall is a $2 billion business for the state, employing fully 8 percent of the workforce.So to try and preserve its profit margins, the Aspen Skiing Company has recently become a loud voice in favor of congressional action on the climate. In 2007, Schendler testified before the House Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment, calling for a cap on carbon emissions—among other things.

“Our attitude when we go to Congress is, look, we’re a business!” he adds. “We didn’t ask for this. We just started looking at the data and the science dispassionately and said, look, we’ve got a problem.”

Another industry that can’t pretend climate change is a myth is insurance. Insurance firms have always carefully studied real-world data to figure out what, precisely, constitutes a risky activity. As a result, they were among the first to notice that weather was getting more violent, and more unpredictably so.

“It’s just a logical consequence,” says Peter Hoppe, head of the “Geo Risks Research” division of Munich Re, the multinational reinsurance firm. “Global warming affects our core business. We have seen changes already in some readings.” Worldwide, Munich Re has found that “great catastrophes”—act-of-god weather events that cause more than a billion dollars of damage— have tripled since 1950. In 2008, even though there weren’t any Katrina-level disasters, weather-related events were so severe that “catastrophic losses” to the world’s economy were the third-highest in recorded history, topping $200 billion globally—including $40 billion in the United States. Hoppe doesn’t think global warming is all to blame; some of these events are likely due to natural cycles like the 30-year “North Atlantic Oscillation” that is currently warming the Atlantic. But Munich Re’s policy is that anthropogenic global warming is already making things worse, and that governments ought to act quickly while they still can.

Granted, a warming globe isn’t just downside for insurance firms. There are also profitable new business opportunities, as Hoppe points out. Munich Re is now offering coverage for renewable energy products, because wind farms and solar parks need insurance against the possibility that low wind and weak sunlight will reduce their output. “It’s very important for investors to dampen and level out the volatility from season to season,” Hoppe says. Munich Re has also developed a product to cover solar cells that wear out before their expected 30-year lifetime.

Buying insurance against bad weather isn’t entirely new. Farmers have done it for years. But back in the late ’90s, before Enron imploded, it created a huge new market of selling “weather futures” to electric utilities—hedges that would pay out if, say, a mild summer hurt their sales (because people would use less air conditioning.) After Enron pancaked, weather futures stayed around—still mostly for utilities and farms—but buying them wasn’t easy: You had to personally contact one of the few weather-futures traders who’d set up their own trading desks in the wake of Enron’s dissolution. But with climate-change models predicting increasingly erratic weather, a new generations of startups is heading into the field, figuring that almost any firm might want to hedge against the bad economic effects of weather—such as clothing manufacturers (who could suffer massive losses in coat sales if an unexpectedly mild winter emerges) airlines (since weather is the top cause of delays) or sporting-event promoters (when it’s rainy, everyone stays away).

Weatherbill is one such startup. Founded three and a half years ago by Google expatriates, it lets anyone use their website to quickly create weather insurance for almost anything. Type in the thing you’re trying to insure—say, an Iowa county fair in the third week of July—and the Weatherbill system calculates the probability of what the local weather will be like up to two years out, down to a 100-mile-wide area. It then uses that guess to instantly price a weather future or insurance contract. CEO Dave Friedberg told me Weatherbill had already sold contracts to the likes of the US Open, and that he envisions worldwide opportunities: Global agriculture suffers billions in weather-related losses each year, for example, yet many countries don’t have any institutions offering easy weather insurance. That’s especially true for countries likely to be the first to experience the dire consequences of climate change, such as coastal regions of Asia or Latin America.

“If you think about Brazil, their two biggest industries are mining and agriculture,” Friedberg says. “That’s billions of dollars, and there’s a massive market for developing crop insurance. If we can figure out agriculture and do it right, the opportunity is huge to go country by country.” Does he believe that global warming is already noticeable? “Oh yeah,” he says. In just the three years that Weatherbill has been collecting data, extreme weather events have risen 8 percent.

One of the big political questions of climate change is how far we’ve gone: Have we passed a tipping point of no return? Has the atmosphere already accumulated such high levels of greenhouse gases that even if we manage to cut back on emissions, we’ll still wind up with a globe so much hotter that everyday life will change significantly? One emerging sector built on the assumption that we have is the “adaptation marketplace“— firms offering new products and services to help companies and cities cope with changes. A 2009 study by Oxfam identified seven potentially lucrative adaptation areas, such as water management and disaster preparation; one firm in this field—the Minneapolis-based Pentair Inc., which makes pumps and filtration systems—has soared to $3.35 billion in annual revenues, partly due to contracts from the Army Corps of Engineers to provide massive pumps that will protect New Orleans against another Katrina. Another firm, North Carolina’s WeatherPredict, has developed a technique to retrofit roofs with aerodynamic edges, reducing the damage they sustain in hurricane winds. Firms that produce genetically engineered crops are also predicting they’ll reap profits from climate change: Monsanto, Bayer, BASF, and their sister firms have registered 55 worldwide patents for “climate ready” seeds designed to thrive in conditions of drought or other stress, according to a 2008 report by ETC Group, an environmental advocacy organization.

Will all this climate-propelled economic activity be good for the planet? Sure, it can be satisfying to see some major CEOs agree that climate change is a real and present danger. But many environmentalists predict that the flurry of new economic activity will create its own new problems.

The melting Arctic, in particular, gives many observers the willies. It’s likely to see an explosion in seabed oil-and-gas exploration and tourism. (Cargo shipping, interestingly, is likely to increase at a slower rate, partly because cargo ships ferrying “just in time” products can’t abide the delays that even small ice floes would cause—and nobody thinks the Arctic will be entirely ice-free for 100 years or more.) Arctic experts—and the Navy—predict a catastrophe the first time a tourist vessel or oil tanker hits an iceberg and cracks up. “Tourist vessels aren’t ice-hardened, and in the polar regions “there’s no search and rescue or salvage,” standing by says Lawson Brigham, a University of Alaska professor who chaired the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment, a four-year study of how the commercial activity will progress in the warming north. “The water’s near freezing. All you need is one good Titanic.”

Other realms of climate-change commerce aren’t much prettier when you look at them closely. In agriculture, the advent of climate-ready crops is clearly useful, maybe even crucial, for adaption. But it also concentrates ever more power in the hands of a small coterie of firms that own the patents to drought-resistant seeds, and the cost could cause serious hardship in the desperately poor countries of Asia or Africa, where the seeds might be most needed.

And it’s also true that the number of climate visionaries in industry is still quite small. Certainly, companies with skin in the game are preparing for a warmer world. But as the McKinsey report found, they’re in the minority. The grand majority are deeply myopic, focused narrowly on goosing profits in the next quarter—who cares what’ll happen ten years from now? (Read Felix Salmon what makes most businesses so shortsighted here.) In a sense, that makes them mildly agnostic force. When climate change finally does impinge on their business, they’ll probably take action to adapt to it. But it also means that if they can see a short-term profit from fighting against climate science and sowing doubt, they’ll do that, too. This is precisely what’s still happening in the energy industry, where many firms that pay lip service to the reality of climate change also quietly funnel millions to lobbyists who fight ferociously to prevent Congress from passing laws that curtail C02 emissions.

“We all know big companies who are doing all this green stuff, and their lobbyists are trying to kill the carbon bill as quickly as they can,” says Mindy Lubber, president of Boston-based CERES, an association of environment-minded investors whose members have $10 trillion under management.

It may be that the corrective force comes not from inside corporations, but from investors. Many large investors, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System—the nation’s second largest public-pension fund—have begun demanding that firms examine and disclose any potential risks from global warming. Shareholder resolutions demanding action on climate change have nearly doubled in the last two years, rising from about 55 in 2007 to 99 in 2009, Lubber notes. In February, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued guidelines requiring that publicly traded firms better disclose their climate-change risk, including potential “physical” risks. (Read a live Grist forum on the new SEC regulations here .)

“Anyone that’s building out new manufacturing facilities without working out water shortages related to climate change is getting itself into trouble,” Lubber adds. “Or anyone that’s building on waterfront property.” Another common request from shareholder resolutions is for companies to calculate the cost of their carbon footprint. Even if electric utilities and the US Chamber of Commerce are fighting against carbon-limiting legislation, investors seem to believe it is inevitable—indeed, they evidently think the government might cap carbon even in the next few years, which could dramatically increase the cost of electricity.

To make corporations true partners in tackling climate change, Lubber thinks investors need to push for basic changes in the way their companies function. CEOs whose bonuses are based on bumping next-quarter results will make short-term decisions. Those who are paid based on reducing carbon usage will make long-term ones—investing in technology and processes that reduce greenhouse gases. “If they’re compensated for producing 86 percent more widgets, they’ll do that. But if they use less fuel, they ought to be compensated for meeting their carbon-reduction goals.”

In the short run, though, there’s probably only one force that will get today’s blithe firms to snap to attention–and that’s legislation. If Congress actually puts a price on carbon, it’ll hit the world of industry with tsunamic force. At minimum, it would probably goose the price of electricity and make emissions-heavy industries instantly less profitable. (Indeed, this is one of the things the SEC and many investor groups are urging firms to do: calculate how badly they’ll be shellacked if new regulations make carbon expensive.) Not everyone will be a loser. The McKinsey study calculated that alternative-energy firms will do quite well (for obvious reasons), but so will less-predictable sectors like the construction industry, as people rush to retrofit buildings with extra insulation and energy-saving rebuilds. The farsighted firms—and the ones who work on the colder fringes of the world—can see the future clearly, because they’re living it. But with the stroke of a pen, Obama can bring it a lot closer. Whether it’s a melting Arctic or a bold new law, the biggest forces shaping industry are, as it were, man-made.