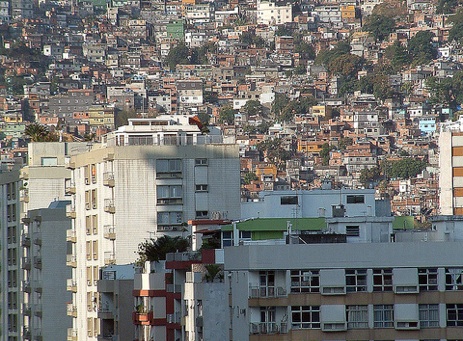

In Rio de Janeiro, the city’s slums are a world away from more modern highrises.Photo: Domenico MarchiThe glossy cities of the world’s wealthiest nations could learn a thing or two about sustainable living by studying the downtrodden slums and shantytowns around the globe, where a billion people make their homes.

In Rio de Janeiro, the city’s slums are a world away from more modern highrises.Photo: Domenico MarchiThe glossy cities of the world’s wealthiest nations could learn a thing or two about sustainable living by studying the downtrodden slums and shantytowns around the globe, where a billion people make their homes.

That’s what architects and urban designers Pavlina Ilieva and Kuo Pao Lian are saying, in an article first published at The Futurist and reprinted at Shareable.

Ilieva and Lian, who live and work in Baltimore, aren’t trying to sugarcoat the poverty and misery found in the favelas of Rio or the barrios of Mexico City. They do think that the folks who live in the planet’s most economically privileged enclaves could learn a lot by looking at these less well-endowed places with an open mind.

It’s not a new idea — back in 2009 Prince Charles famously called the Dharavi slum in Mumbai, where the film Slumdog Millionaire was set, a model for the Western world. Said the prince: “I strongly believe that the West has much to learn from societies and places which, while sometimes poorer in material terms are infinitely richer in the ways in which they live and organize themselves as communities … It may be the case that in a few years’ time such communities will be perceived as best equipped to face the challenges that confront us because they have a built-in resilience and genuinely durable ways of living.”

Charles was blasted by some for his naivete. But Ilieva and Lian agree with him. In an increasingly crowded and urbanized world, they write, planners shouldn’t ignore the successful aspects of slums:

Environmental futurist Stewart Brand and San Diego architect Teddy Cruz have spent years trying to learn and communicate the lessons of these places: They’re high-density and walkable, two goals most urban designers consider of utmost importance when planning multibillion-dollar neighborhoods for hip, wealthy Americans. Commerce and housing in these informal cities mingle freely to the betterment of both residents and shopkeepers. In the West, we hear a lot about the need to recycle. Slum residents have always made use of post-recycled material more effectively than anyone else, including the stuff no one else will take …

The total absence of planning is not a goal for urban planners to strive for. But people in these areas have been surviving and developing with very little capital or government involvement, and they’re becoming increasingly good at it. If we can learn what these places have to teach us, we can find better ways to live in our own local habitats …

Modern life is frustrating and disappointing; we work too hard to spend too much for things we hardly want. The most obvious alternative to our feelings of technological discontent and disconnect is leaving the world behind, quitting the high-stress job, abandoning society with its regulations and failing institutions, moving somewhere temperate, and looking out for oneself. This is popularly referred to as “going off the grid,” meaning the electrical grid, but really referring to any and all sense of society or obligation.

We propose living on the grid of a new urban fabric that distributes self-generated resources — food, learning, skills, human talent, and labor — and creates natural connections among inhabitants and nature. This way of living draws from the lessons that the world’s poorest inhabitants have to give us without romanticizing the difficult and unfortunate aspects of impoverishment.

The developed world has been a lot better at exporting its highly planned, auto-intensive design practices than it has been at creatively incorporating the best of more informal urban patterns.

That may be changing, though. In the United States, crumbling Rust Belt cities like Detroit are providing a sort of experimental space where people can try out this kind of “on the grid” solution — producing their own food, bartering with neighbors, sharing labor, and reusing discarded resources. In the process, they’re transforming blighted neighborhoods by using exactly the kind of approach that Ilieva and Lian are advocating.

No one wants to live in a slum. But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn from them.