You don’t need to go to a place like Ethiopia to get a firsthand look at population growth — we can see its impacts all around us, from sprawling suburban subdivisions to crowded highways and mega-malls. But poor, developing countries like Ethiopia have their own kinds of population challenges, a big one being that many women still lack any access to family-planning tools and information. I recently had the opportunity to see some of these challenges with my own eyes — and to see some impressive progress being made to tackle them.

You don’t need to go to a place like Ethiopia to get a firsthand look at population growth — we can see its impacts all around us, from sprawling suburban subdivisions to crowded highways and mega-malls. But poor, developing countries like Ethiopia have their own kinds of population challenges, a big one being that many women still lack any access to family-planning tools and information. I recently had the opportunity to see some of these challenges with my own eyes — and to see some impressive progress being made to tackle them.

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, with almost 90 million citizens, and it has one of the highest fertility rates in the world — 5.4 births per woman. But the country also has a pioneering new program that’s lowering its birthrate even as it works to improve the health of all of the country’s citizens.

Meet Yitayish Tsige, 27 (in the photo below, left), and Aziza Ismael, 24 (right) — they’re on the front lines of Ethiopia’s health-care push and efforts to give women better reproductive care.

They and 30,000 other young women serve as rural community health workers all around the country. They get a year of training in basic preventive health care and then head back to their home communities to teach hygiene and nutrition, administer childhood immunizations, help people put up bed nets to keep out malaria-carrying mosquitoes, offer basic prenatal care, and attend to births if mothers can’t get to hospitals. The health extension workers, as they’re called, operate in pairs and serve about 5,000 people, spending much of their time going door to door, aided by a handful of volunteers.

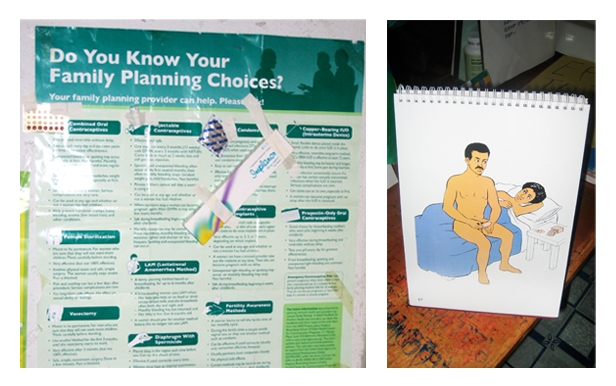

One of the health workers’ big responsibilities is providing family-planning information and contraception. They walk couples through their options with wall charts and an illustrated book:

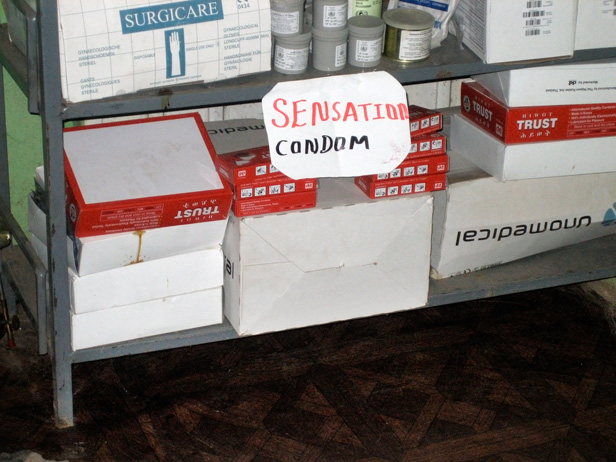

They offer free contraceptives — distributing condoms and the Pill, giving Depo-Provera shots (which work for three months), and inserting Implanon implants (which work for three years).

These family-planning services are transforming lives, like Fatuma Galato’s. Here she is, below, with four of her eight children in front of her home in the rural village of Daka Werekelo, about 150 miles south of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa:

Her first seven children were spaced close together, a consequence of having no access to birth control. When health workers brought contraception to her community, she started using Depo-Provera and was then able to wait six years before having her eighth child (shown here in her arms). He’s the last one, she said; she’s now back on Depo.

Family planning came late to Fatuma. “We suffered a lot from ignorance, but now things are improved for the next generation,” she said. That includes her 17-year-old daughter (on the right below, inside the family’s two-room home), who will have many more options than her mother.

Amina Leriso (left in the photo below), who lives in the village of Galato, is another woman who was only introduced to family planning after she was well into her childbearing years. She started using contraception after her fourth child, then went off it so she could have one more, whom she’s expecting right now. While Amina herself wants a large family, that’s not what she wants for her daughters, including 17-year-old Neima Bederu (pictured here on the right). “My wish for my daughter is to see her complete her education, get a good job, earn a salary, be independent, and live on her own,” Amina said.

Tagesse Atara (left in the photo below) and Beletech Nigatu (right), a married couple, serve as community health volunteers in Galato. They spend two mornings a week spreading information to their neighbors, and they model good health practices for the community. Thanks to family planning, the couple has been able to space out their children — they have a son who’s 7 and a daughter who’s 1. Beletech now has an Implanon implant. They haven’t decided whether to have more kids; they say it will depend on future earnings from their farm.

Chaltu Wata, 20 (left in the photo below), and Aster Roba, 22 (right), are two more health extension workers, based in Daka Werekelo. Aster comes from a family of 10 kids. Her mother, with no birth-control options, had about one child a year, and almost died when her 10th birth turned out to be a complicated one. Aster, who doesn’t want anyone to suffer like her mom did, says that teaching people about family planning is the best part of her job. She herself is unmarried and for the time being uninterested in marriage; she said maybe she’ll get around to it when she’s 35. For now she wants to concentrate on her career and further her education.

Diriba Degeta, 24 (below), is also planning to postpone parenthood. He trained as a nurse and now works in the health system at the district level. He wants to marry in his early 30s and have three kids max, he said.

Ethiopia’s health extension program is simple but ingenious. (Don’t take my word for it; Melinda Gates says so too.) Since its launch in 2004, the program has established 16,000 health posts (small buildings, usually without electricity) in rural communities around the country, where health workers with local roots provide basic preventive services. It makes great sense in a country where 84 percent of people live in rural areas (separated from hospitals by long distances, bad roads, and a lack of cars), and where doctors are in serious short supply (many Ethiopian physicians, when their training is complete, leave the country for more lucrative opportunities). Over the first five years of the program, the ratio of health workers to citizens went from 1-to-30,000 to 1-to-2,500.

The program also appears to be creating a new generation of feminists — young women pursuing careers outside the home, empowered to provide vital services to their communities, earning the respect of their neighbors, and serving as role models for young girls, like these below, who are clustered just outside a health post:

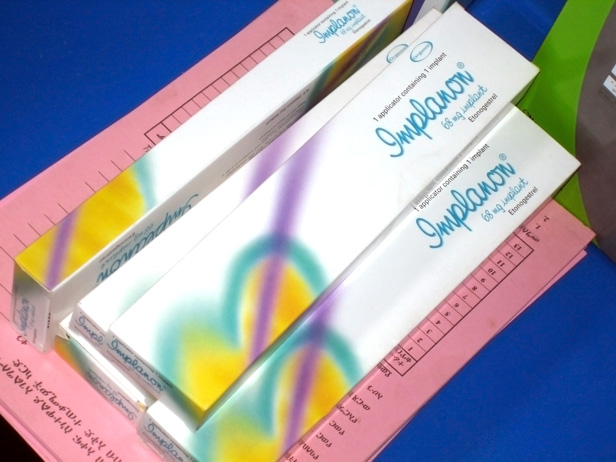

Of course, the health extension program is just a start — Ethiopians need much more. And even the system that’s now up and running has many shortcomings. Take, for one, contraceptive supplies. The health posts aren’t always able to offer what women want. Implanon implants have only been available for a few months in some areas, but they’re already in high demand from women eager for a method that works for three years. One health post I visited had an ample supply of the implants themselves (see below), but didn’t have the kits needed to insert them, which include local anesthetic, a syringe, gloves, and bandages. And while health extension workers can insert the implants when they have all the necessary supplies, they don’t have the skills and training to take them out, so if women have unpleasant side effects or want the implants removed for other reasons, they have to find their way to a higher-level medical professional. Considering the potential side effects of Implanon, this is a serious concern.

Solving these kinds of logistical problems is just one of oh so many challenges facing Ethiopia, complicated by the fact that most of its funding and supplies come via international donors and NGOs, each of which has its own agenda.

If current growth patterns continue, Ethiopia is projected to just about double its population by 2050 to 174 million, making it all the more difficult for its people to climb out of poverty. The government’s official goal is to get the fertility rate down from 5.4 births per woman to 2.1 within five years — extraordinarily ambitious. But even if it isn’t met, the effort to spread family planning far and wide will improve the lives of millions of Ethiopian women and their families.

A big thanks to Population Action International and Pathfinder International, which together sponsored my trip to Ethiopia. They do critical work to spread family-planning services and better overall health care around the world.