Comparisons between Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick (D) and President Barack Obama are tough to avoid. Both spent formative years on Chicago’s South Side, both are Harvard Law graduates, both are post-Civil-Rights-era African Americans who ran on hopeful themes (Obama’s “Yes we can” in 2008 and Patrick’s “Together we can” in 2006).

They’ve also both adopted forward-looking energy plans — and they’ve both seen them constrained by economic calamity set in motion before they took office.

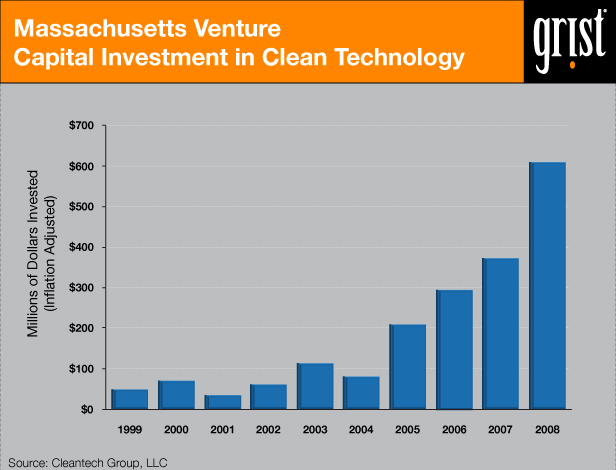

Still, Patrick has racked up a number of environmental accomplishments in the past four years, backing and signing climate and “green communities” bills and forming a Clean Energy Center that provides financing and counsel to the state’s fast-growing cleantech sector. Massachusetts’ cleantech venture funding has risen more than 12-fold in a decade, higher than any state but California, according to a Pew Charitable Trusts report.

This fall, Patrick is defending this record against two challengers from the right who say economic recovery hasn’t come quickly or efficiently enough, and one from the left who says he hasn’t made enough environmental progress. Republican Charlie Baker, a former health-care executive and state finance secretary, presents the biggest threat, running within four points of Patrick in recent polls. Independent Tim Cahill, who’s polling at 10 percent, could end up helping Patrick by splitting the anti-incumbent vote. But Green-Rainbow candidate Jill Stein, polling at 4 percent, could cut into Patrick’s support from progressives.

This fall, Patrick is defending this record against two challengers from the right who say economic recovery hasn’t come quickly or efficiently enough, and one from the left who says he hasn’t made enough environmental progress. Republican Charlie Baker, a former health-care executive and state finance secretary, presents the biggest threat, running within four points of Patrick in recent polls. Independent Tim Cahill, who’s polling at 10 percent, could end up helping Patrick by splitting the anti-incumbent vote. But Green-Rainbow candidate Jill Stein, polling at 4 percent, could cut into Patrick’s support from progressives.

No issue has crystallized the major candidates’ differences on energy more than Cape Wind, the much (much, much) delayed wind farm planned for Nantucket Sound. As the country’s potential first offshore wind installation, it’s taken on symbolic significance. It has actual significance too: The project would generate about three-fourths of the electricity for Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard (combined summer population: 350,000).

Patrick has been a vocal Cape Wind defender, noting the estimated 1,000 jobs it would create and the start it would give the state in the offshore wind industry. Baker and Cahill oppose it based on projected electricity rates, with Baker suggesting instead that the state get more power from the Canadian utility Hydro Quebec. It’s become one of the few energy issues playing a prominent role in a gubernatorial race anywhere this fall.

Another important issue is the state’s participation in the Northeast’s 10-state cap-and-trade system, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Patrick’s predecessor, Mitt Romney (R), originally joined RGGI, then pulled the state out as he prepared for a presidential run. Patrick rejoined the system in one of his first moves as governor. In RGGI’s two-year history, greenhouse gas reductions have been meager (as designed), but the sky hasn’t fallen as cap-and-trade doomsayers warned. Clean-energy businesses have responded with growing investment, and allowance auctions have generated a tidy $729 million for broke state governments, including $115 million for Massachusetts.

Patrick remains committed to the system, but Baker gave a noncommittal assessment last week: “I’m willing to participate as long as it doesn’t cost Massachusetts jobs and money … I don’t know if I’m against it or not. I view that as something that needs to be reviewed.” Earlier this year, Baker said he didn’t know whether climate change was human-caused. He later said that it was human-caused but added that he opposes cap-and-trade (it wasn’t clear whether he meant a national system or RGGI).

One state environmentalist who has worked with Baker said the candidate, despite some of his public comments, aligns with other moderate Republican governors in Massachusetts who’ve worked for environmental goals. “I think he’s is smart enough to know the importance of climate change and efficiency,” he said. “[Although] some of his campaign rhetoric is worrisome.”

Charlie Baker

Charlie BakerPhoto: John GilloolyBaker’s political experience comes from his time as secretary of administration and finance under former Govs. William Weld and Paul Cellucci, where he helped design the financing plan for Boston’s Big Dig tunnel project. His chief business experience comes from 10 years as CEO of the nonprofit Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Charlie BakerPhoto: John GilloolyBaker’s political experience comes from his time as secretary of administration and finance under former Govs. William Weld and Paul Cellucci, where he helped design the financing plan for Boston’s Big Dig tunnel project. His chief business experience comes from 10 years as CEO of the nonprofit Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

He hasn’t said much about energy or climate on the campaigned trail and skipped a candidates’ forum on the environment. But his website offers more nuance and understanding than the average Republican this year, mentioning the economic potential of clean energy and efficiency.

“I’m concerned about the effects of climate change on our environment,” he says on the site. “… Massachusetts is uniquely poised to take advantage of alternative energy sources, which have the potential to save taxpayers and businesses money on their electric bills and will reduce our dependence on foreign oil.”

He backs an LED rebate program to promote more efficient lighting and wants to waive sales tax on energy-efficient appliances and renovations.

Lora Wondolowski, executive director of the state League of Environmental Voters, which has endorsed Patrick, is not impressed by Baker. “He’s not thinking expansively enough about things we could be doing to create jobs in Massachusetts,” she said. “There seems to be a lot of looking to the past instead of the future from Baker and Cahill.”

Baker’s comment about “reviewing” the regional cap-and-trade plan has stirred up concern in the MIT- and Harvard-centered cleantech industry, even if he doesn’t intend to pull out, according to Berl Hartman, an industry consultant and board member for the New England Clean Energy Council. “That makes the clean energy community very, very nervous,” she said. “Most people in the clean energy community think that RGGI is doing quite well and needs to be strengthened.”

Baker hasn’t said much on smart growth or transportation. He opposes a $2 billion South Coast commuter rail project that Patrick backs, saying the area needs school funding more than train service. (This puts him in the same camp as a number of other Republican governor candidates opposing rail projects this year.)

Deval Patrick

Patrick worked as an assistant attorney general for civil rights under President Clinton, and later led an equality and fairness task force at the oil company Texaco.

In his 2006 campaign, he promised to promote the cleantech industry. Hartman says he took a number of important steps to fulfill that pledge, including rejoining RGGI and signing the Global Warming Solutions Act , which requires a greenhouse gas cut of 10 to 25 percent by 2020, and 80 percent by 2050. He also signed the Green Communities Act , which requires utilities to meet their needs through efficiency rather than new generation whenever it’s cost-effective, sets stronger building efficiency codes, and allows net metering so renewable-energy producers can sell their power at competitive rates. It also created a host of incentives, funded by the RGGI cap-and-trade auction, for cities and towns that take steps to cut energy waste and develop in ways that are transit- and pedestrian-friendly. Patrick pushed to make the law stronger than it might have been, Hartman said.

Patrick has been eager to talk about his energy vision. “Climate change is the challenge of our times and we in Massachusetts are rising to that challenge,” Patrick said at a signing ceremony for the Green Communities Act.

He also gave vocal support to the state’s Oceans Act, signed in 2008, which created a first-in-the-nation ocean management plan, essentially a zoning law for state-controlled waters that considers fishing, shipping, potential wind and tidal energy farms, and other uses all together, rather than through separate offices.

Patrick’s record on land and transportation planning has been less distinguished. His predecessor, Romney, created an innovative Office of Commonwealth Development to integrate smart growth considerations of housing, transportation, and economic development in one high-level office, and tapped prominent state environmentalist Doug Foy to run it. The Obama administration used it as a template when it created the Partnership for Sustainable Communities among three cabinet agencies. But Patrick dismantled the office. Several sources also fault Patrick’s administration for not using transportation funding strategically to promote smart growth.

Tim Cahill

Cahill, the independent candidate and current state treasurer, earned a spot on the League of Conservation Voters’ “Dirty Dozen” list this year for opposing Cape Wind and mass transit and generally being skeptical that environmental and economic improvements could go hand in hand. At a forum, the former Democrat said he would promise environmentalists “a seat at the table,” but nothing more until the economy improves. His running mate quit this week to endorse Baker, an embarrassing setback.

Jill Stein

The Green-Rainbow Party candidate is running to the left of Patrick, calling him overly friendly to big business and too timid on clean energy. On her website, she proposes creating a “jobs bonanza” by building a “secure renewable energy economy rather than continuing to waste money on an unsustainable oil-addicted economy.”

——-

Note: Some of the comments below pre-date this story, since we launched our Gubernatorial Tutorial series before publishing this article. Let the conversation continue!