This post was written by Alexandra Giese, staff researcher at the Earth Policy Institute.

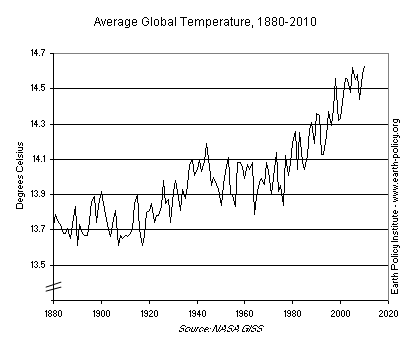

Topping off the warmest decade in history, 2010 experienced a global average temperature of 14.63 degrees Celsius (58.3 degrees F), tying 2005 as the hottest year in 131 years of recordkeeping.

This news will come as no surprise to residents of the 19 countries that experienced record heat in 2010. Belarus set a record of 38.7 degrees Celsius (101.7 degrees F) on August 6 and then broke it by 0.2 degrees Celsius just one day later. A 47-degree Celsius (117-degree F) spike in Burma set a record for Southeast Asia as a whole. And on May 26, 2010, the ancient city of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan hit 53.5 degrees Celsius (128.3 degrees F) — a record not only for the country but for all of Asia. In fact, it was the fourth hottest temperature ever recorded anywhere. (See data at www.earth-policy.org/indicators/C51.)

The Earth’s temperature is not only rising, it is rising at an increasing rate. From 1880 through 1970, the global average temperature increased roughly 0.03 degrees Celsius (0.054 degrees F) each decade. Since 1970, that pace has increased dramatically, to 0.13 degrees Celsius (0.23 degrees F) per decade. Two thirds of the increase of nearly 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees F) in the global temperature since the 1880s has occurred in the last 40 years. And nine of the 10 warmest years happened in the last decade.

Global temperature is influenced by a number of factors, some natural and some due to human activities. A phenomenon known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation is characterized by extremes in Pacific Ocean temperatures and shifts in atmospheric patterns. The cycle involves opposite phases, both of which have global impacts. The El Niño phase typically raises the global average temperature, while its counterpart, La Niña, tends to depress it. Temperature variations are also partly determined by solar cycles. Because we are close to a minimum in solar irradiance (how much energy the Earth receives from the sun) and entered a La Niña episode in the second half of 2010, we would expect a cooler year than normal — making 2010’s record temperature even more remarkable.

Since the Industrial Revolution, emissions from human activities of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide have driven the Earth’s climate system dangerously outside of its normal range. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have risen nearly 40 percent, from 280 parts per million (ppm) to almost 390 ppm. As the atmosphere becomes increasingly overloaded with heat-trapping gases, the Earth’s temperature continues to rise.

Even seemingly small changes in global temperature have far-reaching effects on sea level, atmospheric circulation, and weather patterns around the globe. Climate scientists note that increases in both the frequency and severity of extreme weather events are characteristics of a hotter climate. In 2010, the heat wave in Russia, fires in Israel, flooding in Pakistan and Australia, landslides in China, record snowfall across the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and 12 Atlantic Ocean hurricanes were among the extreme weather events. The human cost of these events was not small: the Russian heat wave and forest fires claimed 56,000 lives, while the Pakistan floods took 1,760.

Although the weather of 2010 seems extreme compared with that of earlier years, scientists warn that such patterns could become more common in the near future. And while no single event can be attributed directly to climate change, NASA climate scientist James Hansen notes that the extreme weather of 2010 would “almost certainly not” have occurred in the absence of excessive greenhouse gas emissions. Warmer air holds more water vapor, and that extra moisture leads to heavier storms. At the same time that precipitation events are becoming larger in some areas, climate change causes more intense and prolonged droughts in others. By some estimates, droughts could be up to 10 times as severe by the end of the century.

Like a growing number of extreme weather events, an increase in the number of record-high temperatures — and a concomitant decrease in the number of record lows — is characteristic of a warming world. For instance, while 19 countries recorded record highs in 2010, not one witnessed a record low temperature. Across the United States, weather station data reveal that daily maximum temperature records outnumbered minimum temperature records for nine months of 2010. Over the last decade, record highs were more than twice as common as record lows, whereas half a century ago there was a roughly equal probability of experiencing either of these.

Temperatures are rising faster in some places than in others. The Arctic has warmed by as much as 3–4 degrees Celsius (5–7 degrees F) since the 1950s. It is heating up at twice the rate of the Earth on average, making it the fastest-warming region on the planet. Disproportionately large warming in the Arctic is partially due to the albedo effect. As sea ice melts, darker ocean water is exposed; the additional energy absorbed by the darker surface then melts more ice, setting in motion a self-reinforcing feedback.

In 2010, Arctic sea ice shrank to its third-lowest extent on record, after 2007 and 2008, and also reached what was likely its lowest volume in thousands of years. At both poles, the great ice sheets are showing worrying signs: recent calculations reveal that Greenland is losing more than 250 billion tons of water per year, and 87 percent of marine glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula have retreated since the 1940s. There is enough water frozen in Greenland and Antarctica to raise global sea levels by over 70 meters (230 feet) if they were to melt entirely.

Unless global temperatures are stabilized, higher seas from melting ice sheets and mountain glaciers, combined with the heat-driven expansion of ocean water itself, will eventually lead to the displacement of millions of people as low-lying coastal areas and island nations are inundated. Sea level rise has been minimal so far, with a global average of 17 centimeters (6 inches) during the last century. But the rate of the rise is accelerating, and some scientists maintain that a rise as high as 2 meters (6 feet) is possible before this century’s end.

It is not only coastal populations that are threatened by rising global temperatures. Higher temperatures reduce crop yields and water supplies, affecting food security worldwide. Agricultural scientists have drawn a correlation between a temperature rise of 1 degree Celsius above the optimum during the growing season and a grain yield decrease of 10 percent. Heat waves and droughts can also cause drastic cuts in harvests. Mountain glaciers, which are shrinking worldwide as a result of rising temperatures, supply drinking and irrigation water to much of the world’s population, including hundreds of millions in Asia.

More than any natural variations, carbon emissions from human activities will determine the future trajectory of the Earth’s temperature and thus the frequency of extreme weather events, the rise in sea level, and the state of food security. The 2007 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected that the Earth would warm 1.1–6.4 degrees Celsius (2–11 degrees F) by the en

d of the century. Yet a rise of 2–3 degrees Celsius will make the Earth as hot as it was 3 million years ago, when oceans were more than 25 meters (80 feet) higher than they are today. Subsequent research has projected an even larger rise — up to 13.3 degrees Fahrenheit — if the world continues to depend on a fossil-fuel-based energy system. But we can create a different future by turning to a new path — one with carbon-free energy sources, restructured transportation, and increased efficiency. By dramatically reducing emissions, we could halt the rapid rise of the Earth’s temperature.

Data and additional resources at www.earth-policy.org.