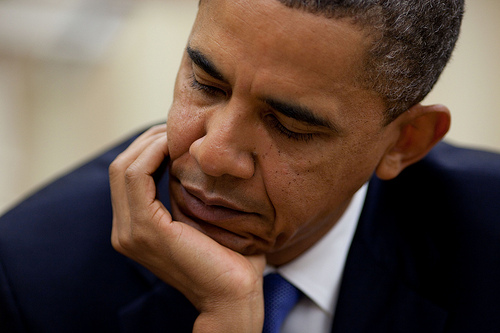

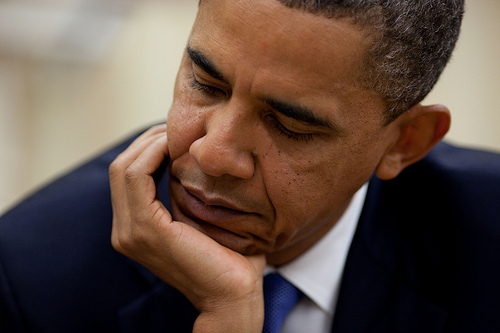

Is Obama’s style of American exceptionalism on its last legs?Arguably the central provision of President Obama’s State of the Union address last night was the proposal to generate 80 percent of the nation’s electricity from clean energy sources by 2035 — including nuclear energy and “carbon capture and storage” coal technology. Getting there will take a miracle, the same sort of pie in the sky thinking that allowed our president to also present the daft notion of giving 80 percent of Americans access to high-speed rail by 2035. This in a country that last built a great rail station over a century ago.

Is Obama’s style of American exceptionalism on its last legs?Arguably the central provision of President Obama’s State of the Union address last night was the proposal to generate 80 percent of the nation’s electricity from clean energy sources by 2035 — including nuclear energy and “carbon capture and storage” coal technology. Getting there will take a miracle, the same sort of pie in the sky thinking that allowed our president to also present the daft notion of giving 80 percent of Americans access to high-speed rail by 2035. This in a country that last built a great rail station over a century ago.

Both ideas, of course, fit neatly into the necessary big box of ideas that can generate the innovation, imagination, inspiration, and transition-era job growth that rebuilds the American economy, and especially the “be all you can be” contract with its people.

But neither is likely to happen. To achieve either goal will take a sharp shift in the political geography on the right and the left, as well as much larger public investments in innovation and financing than the country has been willing to make to date. In an era of fierce and fast-paced transition prompted by the new markets of the 21st century, Americans have expressed time and again their resistance to doing anything more than staying firmly in place. I’ve begun to call our predicament the “amber alert” because we’re so determined to wrap our personal gains and communities in amber.

Republican governors in the Midwest, for instance, want to give back the federal high-speed rail construction money made available last year, and are governing against the clean energy investments that have helped turn solar, wind components, and lithium-ion battery manufacturing into the fastest growing new industrial sectors in Ohio and Michigan.

Let’s quickly evaluate the 80 percent electrical generation goal. To achieve 80 percent clean energy generation essentially means replacing at least 500 gigawatts of conventional coal-fired generation with cleaner alternatives. In essence, the U.S. would have to nearly completely rebuild its electrical generating infrastructure, which last year had about 940 gigawatts of electricial generating capacity. By 2035, according to Department of Energy projections, electrical generating demand in the U.S. could grow to 1,200 gigawatts. Today, less than a quarter of electrical generating capacity is supplied by nuclear power, hydro, wind, and geothermal in the U.S — roughly 225 gigawatts.

To date, the nation has indicated no proclivity to launch a crash program for clean energy investment. The $100 billion provided in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, now threatened by the Republican House majority, is merely a down payment. In fact, the largest energy investment in the nation is being made to drill, mine, process, and transport the unconventional oil and gas reserves being tapped in the middle part of the country.

Moreover, while the right discounts the science of climate change and expresses skepticism about the costs of clean energy subsidies, the grassroots left is digging in to fight clean energy projects of scale. Opposition campaigns are occurring in at least 35 states and focus on every available alternative — wind, solar, geothermal, biomass, and nuclear. Here in Benzie and Manistee counties where I live in northern Michigan, a $330 million proposal by Duke Energy to build 112 wind turbines is the focus of a fear-based opposition campaign that includes scientifically unfounded assertions that the turbine blades generate dangerous sound waves that can cause farm animals to spontaneously abort.

The country that is responding to the new energy market opportunities of the 21st century is China, which commands nearly all of those very same markets. I just returned from a long reporting trip to China for Circle of Blue, the first-rate independent news organization that covers the freshwater crisis. I serve there as senior editor. I visited the largest clean energy industrial park in the world in Gansu Province, as well as some of the largest steel plants, solar farms, and coal mines.

China has set a goal to drive their clean energy diversification program for electrical production — wind, solar, hydro, nuclear, IGGC — from 200 gigawatts currently to over 630 gigawatts by 2020. The breakdown by 2020 looks like this: wind (150 gigawatts), solar (20 gigawatts), nuclear (60 gigawatts), hydro (400 gigawatts).

Still, because of China’s rapidly growing demand for energy — total energy consumption has tripled since 1995, reaching over 100 quadrillion BTUs this year from 35 quads 15 years ago — coal will still be responsible for more than 70 percent of total electrical supply, a little less than it is today.

All that energy supports the world’s largest markets for steel, glass, cement, energy, cars, residential construction, nuclear and coal-fired power plant construction, hydro dam construction, highways, high-speed rail, and a dozen other critical products of modern society. China’s transportation infrastructure has surpassed the United States, as have its grade school students, now the best in the world.

Americans note that China’s political economy is founded on a system that has no veto power. The country acts on what it decides regardless of public opinion. But you have to wonder whether there are facets of that system that are more fit for the time. China also produced 70 million new jobs in the last decade and the incomes of 400 million people are rising, in contrast to diminishing job numbers and steadily declining incomes in the U.S.

President Obama set out worthy goals last night to light at least a spark of national motivation to fix America. But moving forward on any idea of real significance is so difficult he declined to lay out even the most modest specific steps. You wonder whether a quarter century from now a U.S. president will still be able to say, “And yet, as contentious and frustrating and messy as our democracy can sometimes be, I know there isn’t a person here who would trade places with any other nation on Earth.”

Related:

- Obama’s State of the Union energy proposals are … thrilling? bipartisan? misleading?

- Obama’s energy gambit: a call for less coal

- David Roberts on why Obama was wrong not to mention climate change in his State of the Union