Constant warmth punctuated by repeated winter heatwaves stymied Arctic sea ice growth this winter, leaving the winter sea ice cover missing an area the size of California and Texas combined, and setting a record-low maximum for the third year in a row.

Even in the context of the decades of greenhouse gas–driven warming, and subsequent ice loss in the Arctic, this winter’s weather stood out.

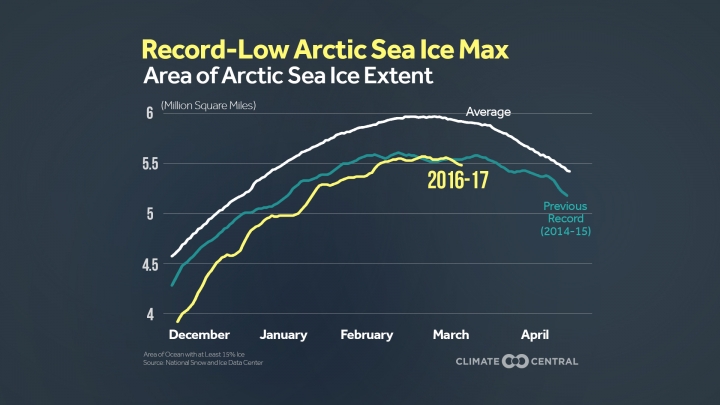

Arctic sea ice extent as of March 20, 2017, compared to the previous record low year and the 1981–2010 average.

“I have been looking at Arctic weather patterns for 35 years and have never seen anything close to what we’ve experienced these past two winters,” Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, which keeps track of sea ice levels, said in a statement.

The sea ice fringing Antarctica also set a record low for its annual summer minimum (with the seasons opposite in the Southern Hemisphere), though this was in sharp contrast to the record highs racked up in recent years. Researchers are still investigating what forces, including global warming, are driving Antarctic sea ice trends.

Sea ice is a crucial part of the ecosystems at both poles, providing habitat and influencing food availability for penguins, polar bears, and other native species. Arctic sea ice melt fueled by ever-rising global temperatures is also opening the already fragile region to increased shipping traffic and may be affecting weather patterns over Europe, Asia, and North America.

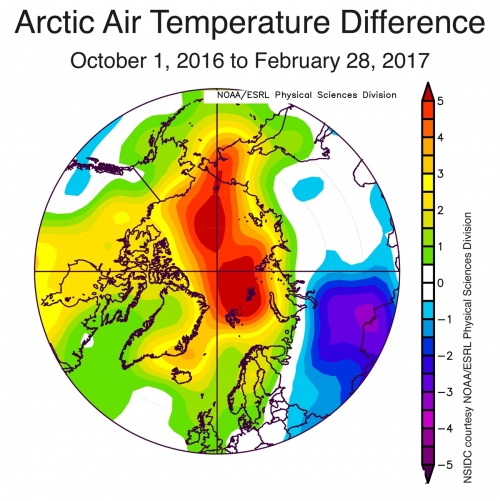

Arctic air temperature differences about 2,500 feet above sea level in degrees Celsius from Oct. 1, 2016, to Feb. 28, 2017. Yellows and reds indicate temperatures higher than the 1981 to 2010 average; blues and purples indicate temperatures lower than the 1981 to 2010 average. NSIDC

The area of the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice usually hits its winter peak in early to mid-March, as the freeze season ends with the reemergence of the sun above the horizon.

This year’s maximum was likely reached on March 7, the NSIDC said Wednesday, when sea ice covered 5.57 million square miles, the lowest in 38 years of satellite records. This area came in just under 2015’s maximum of 5.605 million square miles (the NSIDC slightly revised its numbers for last summer, so 2015’s maximum actually ranks lower than 2016) and 471,000 square miles below the 1981–2010 average, an area larger than California and Texas combined.

Arctic sea ice was also thinner this winter than in the past four years, according to data from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite.

Much of the reason for this thinness and smaller ice area was the consistent warmth throughout the autumn and winter. Across the Arctic Ocean, temperatures during this period were about 4.5 degrees F (2.5 degrees C) above average, with parts of the Chukchi and Barents seas coming in at 9 degrees F (5 degrees C) above average. (The Chukchi Sea lies between Alaska and Russia, while the Barents Sea sits to the north of Scandinavia.)

The Arctic was one of the clear global hotspots that helped drive global temperatures to the second-hottest February on record and the third-hottest January, despite the demise of a global heat-boosting El Niño last summer.

That background warmth was amped up by repeated incursions of warm air brought by storm systems from the Atlantic. During one such episode in early February, temperatures above 80 degrees north latitude reached nearly 30 degrees F (15 degrees C) above normal winter temperatures of about -22 degrees F (-30 degrees C).

The record-low winter maximum doesn’t necessarily herald a record low end-of-summer minimum come September, as summer weather patterns have a large effect on sea ice area. Sea ice was at record-low levels going into last summer, but fairly cool, cloudy conditions during the season held back the melt somewhat. A late-season surge in melt still pushed the summer minimum to the second lowest on record.

In general, though, a low winter maximum means sea ice is already starting off the melt season on the wrong foot.

“Thin ice and beset by warm weather — not a good way to begin the melt season,” NSIDC lead scientist Ted Scambos, said in a statement.

The rate of ice loss has been much steeper for the summer minimum than for winter maximum, with declines of 13.7 percent and 3.2 percent per decade, respectively.

But “while the Arctic maximum is not as important as the seasonal minimum, the long-term decline is a clear indicator of climate change,” Walt Meier, a sea ice researcher at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement.

The recent string of record-low winter maximums could be a sign that the large summer losses are starting to show up more in other seasons, with an increasingly delayed fall freeze-up that leaves less time for sea ice to accumulate in winter, Julienne Stroeve, an NSIDC scientist and University College London professor, previously said.

The Antarctic summer minimum was 813,000 square miles, or 900,000 square miles below the 1981–2010 average and 71,000 square miles below the previous record low set in 1997. In general, Antarctic sea ice is much more variable than the Arctic, and scientists are still grappling with how climate change and various natural climate cycles might be interacting to affect sea ice levels there.