One of the most encouraging things about the sustainable-food movement is how effortlessly it crosses traditional political-party, religious, ethnic, and other lines. The right to good, clean, and fair food, to borrow Slow Food‘s shorthand, seems to unite people who’d never otherwise find themselves chatting at the same party: Home schoolers and dreadlocked hippies, libertarian DIYers and heartland moms.

But there are little pockets of polarization where brawls can break out. One of them is the so-called elitism of such food. The biggest hot-button issue by far, though, is that of transgenic crops. The food movement’s Christian wing opposes it for religious reasons, the Berkeley brigade for dogmatic ones, the moms out of health fears. Those with science or technology backgrounds, however, tend to see genetically modified organisms as just another tool in the how-we-are-going-to-feed-the-world toolbox — and tend to get pretty impatient with those who fear them.

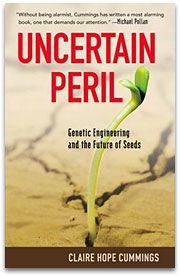

In her new book, Uncertain Peril: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Seeds, Claire Hope Cummings marches through the middle of these often reflexive con and pro positions in search of a more nuanced big-picture view. An environmental lawyer for 20 years, including four spent with the USDA, Cummings now reports regularly on agriculture and the environment. She has also farmed in California and in Vietnam. These experiences inform her book, which chronicles how transgenic seeds came to market; how their corporate backing has affected farmers, biodiversity, and agricultural sovereignty; and what their unfettered spread may mean for humankind.

It’s not a happy picture. Just as Rachel Carson opened Silent Spring with the allegory of a town that woke up to find all the birds gone silent, Cummings said she considered starting Uncertain Peril with a scene in which everyone goes out to check their spring gardens, only to find that nothing has grown. Recently Cummings stopped by my house in Oakland, Calif., (yes, on the Berkeley border) for a chat conducted at her usual breakneck pace.

What motivated you to write this argument against the use of genetic technologies in agriculture?

Because GMOs [genetically modified organisms] don’t seem like an immediate personal threat, their risks to our health and the environment are fairly subtle. They’re real; they’re just not the kind you see on the evening news. There’s a lot of information about those risks already available. I wrote the book because I’m very concerned with the political and moral aspects of the technology. As a public-interest lawyer I was appalled to learn how this was invented and imposed on us. We were never given a choice. There’s a whole matrix of control involved, from the biological level — the way they are engineered — to the social level, how they are being imposed on people and nature.

Let’s start with the biological. Why do you call genetic technology the “defining moral issue of our time”?

Because it dismantles the basic integrity of the natural world. It’s so shortsighted. We don’t know enough about the biological world to know what we’re doing, and we haven’t agreed on an ethical framework for these technologies.

But isn’t the technology itself morally neutral?

Like all tools, technology simply extends the hand of man. But we forget that that hand is connected to the head and the heart. So how it is manipulated is part of the technology. We can talk about science as a set of different tools of inquiry, that can be a little less value-laden, but technology is never anything but a tool that is connected to a value.

Uncertain Peril: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Seeds, by Claire Hope Cummings.

Genetically modifying a plant severs its relationship to its evolutionary course, and inserts into it, by force — using a gene gun or bacteria — some human idea of what the plant should do. The technology is limited both by its violent nature and our imagination. We’re rearranging the molecular structure of these plants because we think we know how this plant should be used. Why, instead of breeding plants with traditional methods and relying on the plant’s own carefully created system for say, drought resistance, would you use a much more expensive, unpredictable process like genetic engineering?

Because of patents. So you can own it. I mean, given all these great tools, what did Monsanto come up with? Herbicide-resistant soybeans to sell more of its chemicals. Most GMOs are plants that don’t die when sprayed with a lethal herbicide, or ones that exude insecticide. That’s Monsanto’s idea of how to use nature to make money. The point of GMOs is control over seeds for profit.

Which brings us to the social-control aspect.

Yes, the ownership issue. For example, Monsanto owns so much of the world’s cotton seed supply now that cotton farmers cannot get conventional [non-GM] seed. It is simply not offered. [Editorial note: Cummings later clarified that while non-GMO conventional seeds may be listed in catalogs, farmers are telling her that when they go to buy it, only GMO seeds are available.] Monsanto also tells farmers they can’t save seeds, reuse them, or even study them. This is the time-honored heart of agriculture. Seeds have always adapted themselves to a specific place and climate. Now, just when we need more food, more adaptability, and natural diversity, millions of dollars’ worth of seeds are being thrown away because of biotech industry contracts.

So this is really about who controls our food supply?

Yes. Is food going to be something the public maintains at the center of our personal and political decision-making, or will we just continue to hand it over to either private corporations (which have a completely different set of interests in mind) or to the government (which is now aligned with these private interests)? That’s what we have now. How are we doing so far? I’d say the sorry state of public health and the environment shows our food system is not healthy.

When Abraham Lincoln created the U.S. Department of Agriculture, he called it “the People’s Department.” The USDA used to send seeds out free every year to gardeners and farmers all over America. The democratic underpinnings of our food system have been dismantled.

Talk to me about the tripod you write about, of “people, plants, and place.”

That’s my favorite way of discussing what we need to return to, what we need to build a productive agriculture on. True productivity, fertility, and health are based on those three things, and all of them are under huge duress right now. We have to go back to understanding that productivity is more of an ecological question and more whole-farm based, looking at the whole farm, the soil. It’s about biodiversity and even the larger human community in and around that farm.

What can we do?

We can save seeds. It doesn’t matter which ones. Calendula is a really pretty, very hardy flower, very generous with its seeds — so easy to save. Have fun and plant stuff. Kids like to see things grow; radishes are easy kid plants. There are so many easy ways to honor our relationship with plants. It’s sort of like a prayer. You may not want to be a priest, rabbi, or the Dalai Lama, but you can have a simple daily prayer of caring for a plant through its entire cycle, and participate in the generosity and integrity of the natural world by growing food and sharing it. It’s a practical spirituality that keeps us grounded in place and community, while giving us the enormous privilege of assisting in the regenerative capacity of the earth.

What it comes down to is whether or not we are going to be allowed to feed ourselves and make informed choices about how we do that — to live in our biological and social reality, which is that people, plants, and place were meant to be working together.