Gov. Jerry Brown recently unveiled a $1.25 billion plan to spend the money raised from California’s cap and trade program. It would put millions of electric cars on the roads, clear tinder from the state’s flammable forests, and replace exhaust-belching motors with cleaner engines. But, according to critics, it wouldn’t do enough for Californians hardest hit by fossil-fuel pollution.

“In terms of allocating funding to disadvantaged communities, it falls real short,” said Emi Wang, environmental equity manager for the Greenlining Institute, a nonprofit working to give people of color a level economic playing field.

In previous years, part of the cap and trade money was spent on creating parks, planting street trees, and helping low-income families make their homes more energy efficient. Brown’s latest budget would scrap all that. There’s also less money than anti-poverty advocates wanted to fund grassroots community projects and monitor potentially harmful pollution. The big winners in the budget are people who want zero-emission vehicles — the spending plan includes rebates for buying electric cars and money for new charging stations.

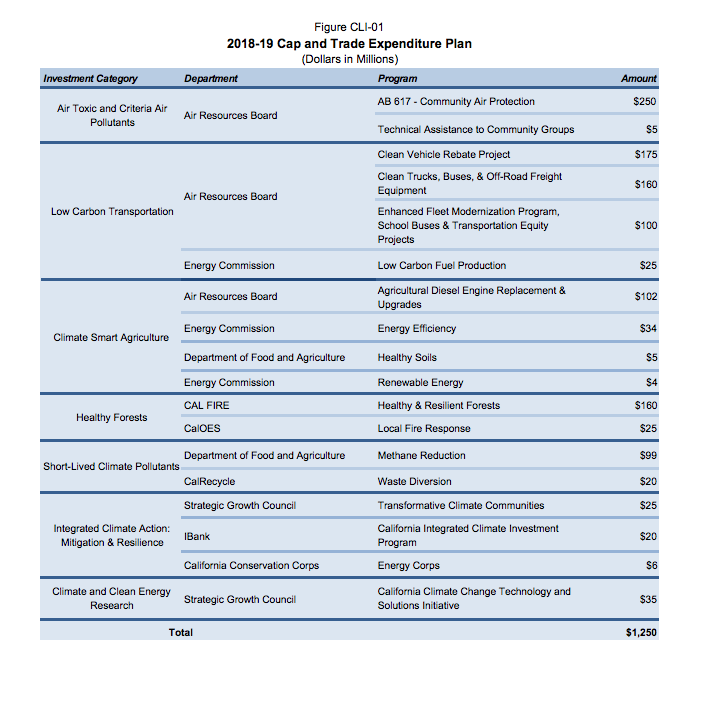

In California, the money flowing from the state’s carbon cap goes into its own bucket, not into the general fund. The governor proposes a separate budget for this money, which the legislature can use as a starting place as it negotiates over the final budget. Here’s an overview of Brown’s initial proposal:

Office of Governor Jerry Brown

Parin Shah, senior strategist for the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, says that California needs to curb vehicle emissions but “what we’d really like to see is money going to programs that have direct benefit to the Californians who have most suffered from the fossil fuel economy.” For instance, installing sensors to watch for harmful pollutants in befouled neighborhoods, or paying for insulation for low-income people to cut their power bills.

There’s some version of this conflict in every debate over how to put a price on carbon. Do you pour the money raised into building the low-carbon infrastructure of the future? Do you use the funds to redress injustice? Do you make a carbon tax revenue-neutral by giving the money back to the people with tax rebates? Often the debate happens in the abstract, before it’s even clear if there’s the political will to tax or cap carbon. In California, we can see how this debate plays out after cap and trade has become a reality.

So who benefits? Is all the money going to help Tesla buyers?

In short, no. “Generally speaking the state has been quite good at getting that money into the hands of the people who need it,” Shah said.

A 2016 California law requires the state to spend a third of the cap and trade money within low-income and polluted communities. For the last two years, the state has been exceeding those standards.

But the rural interior of the state still gets short shrift according to, Nikita Daryanani, policy coordinator for the Fresno-based Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. “Funding leaves out many smaller communities,” she said. A lot of the money is distributed in the form of competitive grants, and small groups from small towns often don’t have resources to figure out how to apply for them, she said.

The Greenlining Institute is trying to fix that. The organization just launched a website to guide people through the process of applying for grants backed by cap-and-trade money. “The state websites are very wonky and enormously complicated,” Wang said. “It’s completely dizzying to figure out for an individual or nonprofit.”

The Greenlining alternative provides access to all that information in a much more user-friendly fashion:

Yet, as Greenlining steps up, Brown has proposed stepping back, with less money for the kind of bottom-up organizing that might provide small community groups the assistance to ask for the help they need.

The governor is taking feedback and will revise the budget in a few months, and the legislature is supposed to hash it over before voting on a final budget by June 15.

Greenlining and the other groups will be lobbying for changes. “While some parts of the proposed budget could help vulnerable communities, these cuts could do real harm to them,” Greenlining wrote in a press release.