Dead bodies starting to thaw on Mount Everest, flooding from glacial lakes, dams bursting and destroying villages: This is a picture of global heating in the Himalayas.

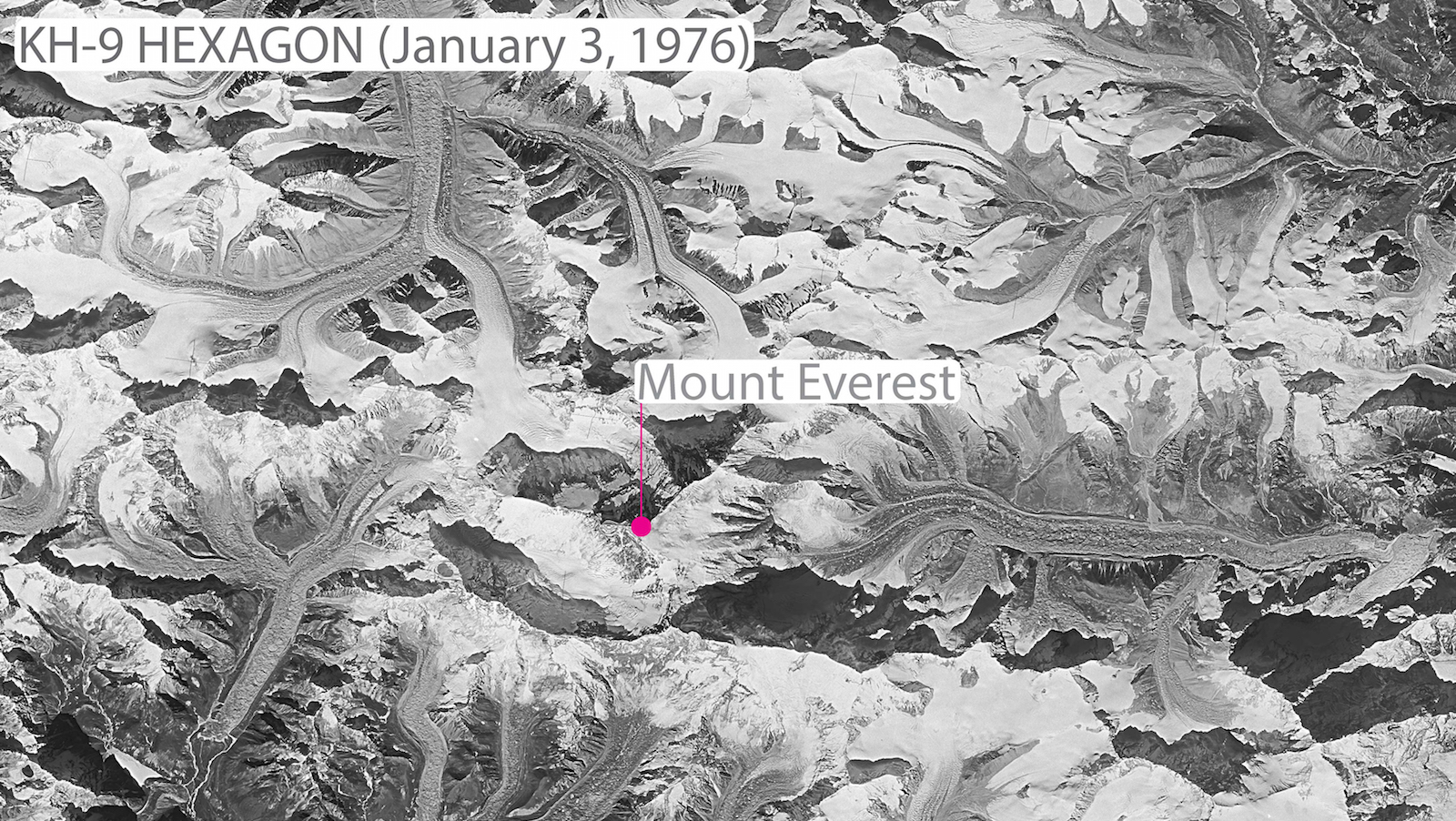

A group of researchers have managed to essentially 3D-map the slow descent of glacial ice in the region over the last four decades using declassified black-and-white film images from Cold War-era spy satellites. The glaciers may have lost as much as a quarter of their mass over the last 40 years due to rising temperatures, said lead author Joshua Maurer, a PhD candidate at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“This is the clearest picture yet of how fast Himalayan glaciers are melting over this time interval, and why,” Maurer said. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The amount of ice loss from 2000 to 2016 was double that from 1975 to 2000. Since 2000, the glaciers have lost enough water to fill 3.2 million olympic-sized swimming pools every year, Maurer said.

A landmark study from earlier this year says we’re already too late to save many of the glaciers in this renowned region; even if the world meets the most ambitious of the three Paris Climate Accord scenarios, over one third of Himalayan glaciers will be gone by 2100 (if no progress is made on emissions, two thirds will melt). The melting could impact drinking water for 1.65 billion people in surrounding countries (China, India, Bhutan).

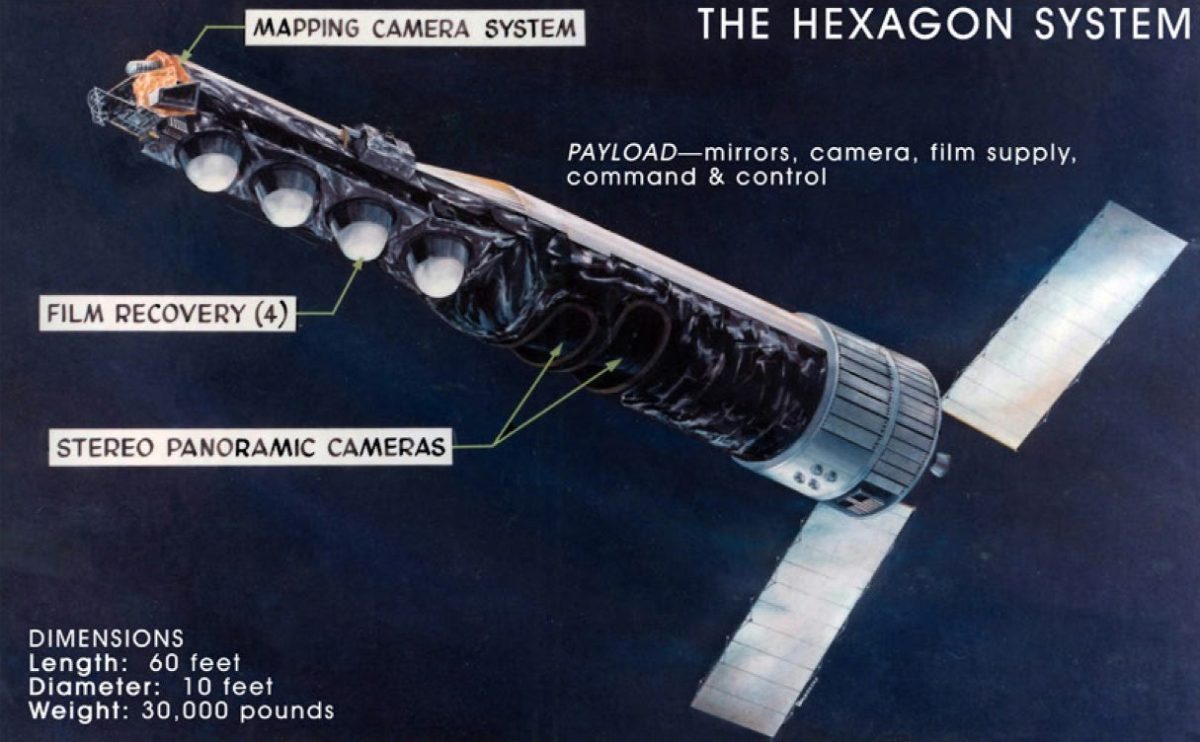

Maurer’s study was made possible by a remarkable data collection. The Hexagon military spy satellites were created during the Cold War to help the U.S. track Soviet troop numbers and weapons development, among other things. Decades before Google maps, the military was able to create high-resolution imagery so accurate, you could supposedly see a picnic blanket from space.

The satellites the U.S. launched into the atmosphere during the Cold War were roughly the size of school buses, and took thousands of images on black and white film. To get the pictures back down to command, the satellite would wait until a film canister was full, then eject it into the Earth’s atmosphere, where it would parachute down until a plane grabbed it with a grappling hook, Maurer explained.

National Reconnaissance Office

The images were classified until then-Vice President Al Gore learned about them, and started the MEDEA program to give environmental scientists access to the data. President Bill Clinton eventually declassified most of it for scientific use in a 1995 Executive Order. Now, “a lot of the actual imagery is open and available for download on the USGS website, and people can use it,” Maurer said.

So what else can this once-secret data tell us about our changing environment? Over the years, NASA scientist Robert Bindschadler used it to study Antarctic ice streams, and environmental scientists were able to track desert expansion in Sudan, Arctic ice melt, and tree growth in Siberia.

As for Maurer, he said he hopes to apply this treasure-trove of declassified data to predict the rate of Himalayan ice loss, so governments can begin to prepare (for example, forgoing building new hydropower dams) and mitigate the damage to villages and people near melting glaciers.

And next, Maurer wants to use the same method to profile ice loss in Chile’s Patagonia region.