Imagine you were just elected governor. Congrats! OK, enough with the celebration already, Grist wants to know: How are you going to clean up your state’s greenhouse gas emissions?

You might push for a carbon tax, or subsidize clean energy, or ban cars from city centers. Even if your strategy is just “do it all,” you still need to figure out what comes first, or what to do if you are low on money. And how do make sure your policy really works?

Here’s where Hal Harvey, head of the clean energy think tank Energy Innovation, steps in. Harvey crunched the data from dozens of countries to see what worked for his new book, Designing Climate Solutions.

“This is kind of a handbook for an energy advisor to a governor, or somebody who is a serious activist who doesn’t just want to write a letter, but wants their activism to be informed by analytics,” Harvey said when we called him up to ask him about it.

He wrote it because no guidebook existed for one of the biggest problems in the world. “It’s not a sexy book,” he said with a laugh, but it offers plenty of surprising insights. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q.Why do we need a book like this?

A.One of the things that worries me is that there’s been a lack of discipline in how we approach climate change. There’s no strategy if everything is equally important. So if we have to divest and become vegans and save the rainforest in Guyana and get a renewable portfolio standard and so on and so forth, there becomes a point where instead of an answer you actually have a suite of non answers or the answers are buried. One of our goals with this book is to create a much sharper focus on how to win, what you have to do if you really want to avoid serious climate change.

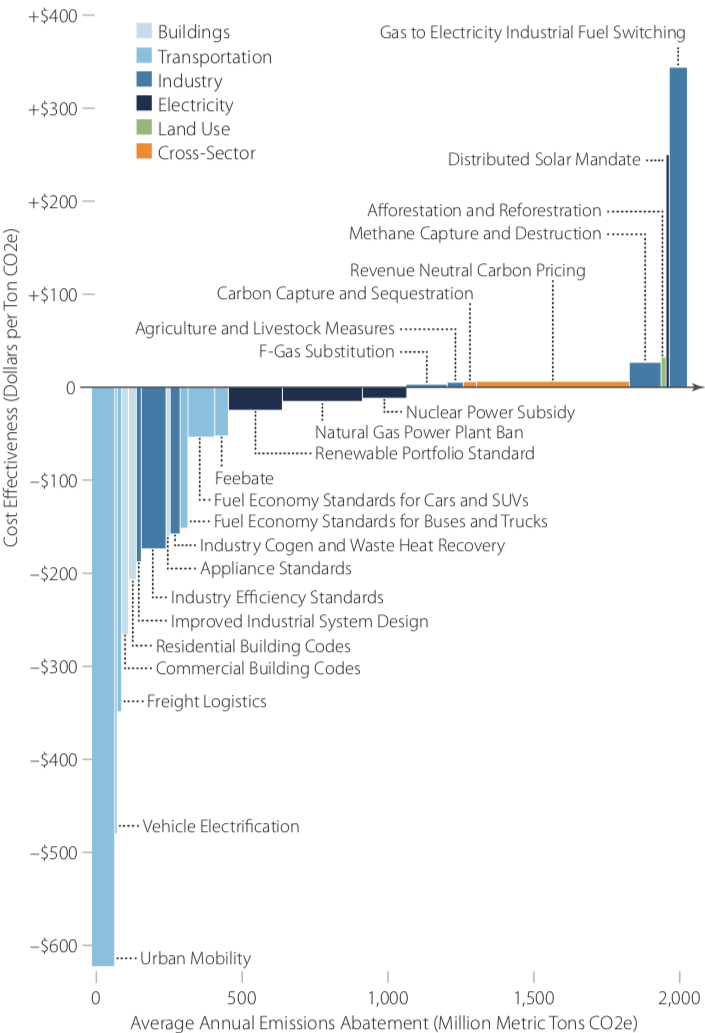

Q.I want to look at one graph from the book, because it demonstrates your point and also contains all sorts of surprises. Can you just explain what this is and how you read it?

A.Each of the bars on this graph is a potential policy. The height of the bar is the cost, or savings if it’s negative, of that policy. The width of the bar indicates how much carbon it would cut. So if you wanted to do best buys first, you’d start on the left and work your way over to the right. If you wanted maximum impact for a single policy, you’d look for the ones spread out the widest.

Energy Innovation

Q.What does it mean that some of these policies cost less than nothing? Take urban mobility: The graph says you can save more than $600 for every ton of pollution you eliminate. What’s stopping people from, say, starting up bus lines to grab it?

A.So, if you have a good urban transit system, for instance, it saves land space that would have been used for parking, it makes the streets less congested, it reduces pollution and health costs, it increases livability. But those do not show up in government budgets, where we can see their costs. Right? We give the atmosphere away for free to pollute, we give the streets away for free to clog with cars.

Q.I see. So every time I get in a car I’m imposing a cost on everyone else by spitting out pollution and making traffic jams worse, though I never have to pay for that. And in this graph, you are making those costs visible.

A.Right. A simpler example, where it’s all private costs, are fuel economy standards. Those make cars cost a little more up front [because engineers need to figure out how to give cars better gas mileage], but you end up saving even more over the long run because you burn less fuel.

Q.You have two types of policy options here: One is “performance standards,” basically rules like gas mileage requirements. Can you tell me about how they work?

A.Performance standards are things like fire codes and meat inspections. We’re used to them. When you take a drink of water, you expect it to be healthy. When you take a bite of meat, you expect it not to be poisoned. When you spend a night in the hotel, you expect that it won’t burn down.

A.We scoot though life taking for granted that elevators aren’t going to plummet down, but all these things are safe because people worked out the particulars. We haven’t done that for clean energy. California has almost the best thermal building code in the world; Texas has none. In Texas, you can build a house with no insulation whatsoever. You can put in the crappiest heater and single pane windows, and you can sell it for a little less. But you’ve created a one-hundred year liability both for the homeowner and for society that has to absorb all the pollution from heating and cooling that house.

Q.So it sounds like performance standards are useful when it’s hard to see the long-term cost of something. I’m realizing that when we bought our house, we didn’t consider its lack of insulation.

A.Even if you could get that information, it would be number 15 on the list of 10 things you were considering. And the people who build and design buildings never have to pay the utility bills. So here’s an instance of where it makes sense for the government to step in and help.

Q.You also talk about economic incentives, like a subsidy for clean energy and carbon taxes. When are they the right choice?

A.If there’s a pretty small cost for switching from dirty to clean — and especially if it’s a complicated business like manufacturing — then an economic incentive can be great. A carbon tax is good for industry, because it has rational engineers working every day to figure out how to minimize costs and maximize profits. It’s useful where energy is a large portion of your expenses, like with aluminum smelters and steel furnaces. And it’s useful to complement performance standards.

Q.On that graph, rooftop solar is relatively expensive and not all that effective, whereas a nuclear-power subsidy saves money and cuts more carbon. California is shutting down its last nuclear plant while requiring solar panels on new houses. Does this graph suggest California is making the wrong moves?

A.Not necessarily. It’s a really good idea to overpay in the early days of a new technology if it promises steep price reductions in the future and being scalable. Solar fits that.