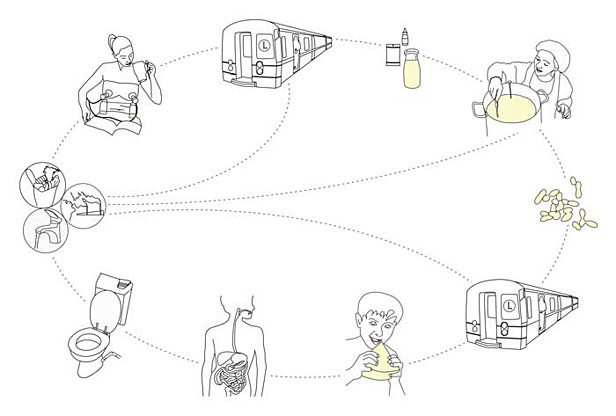

Pondering a lifecycle analysis of human cheese. (Image by Miriam Simun.)

Would you try a slice of human cheese?

I’ve asked this question at a dinner of artists and sustainable food advocates, at dinner with my family, and in conversation with friends. There are the brave few who say they’d be interested in tasting some, but most people react in utter disgust.

After the shock of imagining what it would be like to consume cheese made from human milk, the real question becomes: Why does it make us so uncomfortable?

A Human Cheese tasting at Postmasters Gallery. (Photo by Miriam Simun.)

New York University graduate student Miriam Simun created her Human Cheese project as a way to engage people in conversation about biotechnology, food systems, and the human body. The project originated as part of Marc Alt’s Living Systemscourse at NYU’s Interactive Technology Program, but she plans to continue her research.

I usually focus on information technology, but I was particularly interested in Simun’s innovative approach to exploring the ethics of biotechnology and sustainable food production. She pushes the boundaries in the already contentious and topical conversation of biotechnology, and I wanted to have my assumptions challenged.

How about you? Does the idea of human cheese fascinate or disgust you? Can you articulate why?

Read about Simun’s approach, then share your thoughts below.

Q. What was the inspiration for creating human cheese?

A. I love cheese. I’ve been trying to eat better recently, and there’s so many different considerations that go into “better” food — organic, natural, local, sustainable, free-range, ethical, fair trade. It’s really overwhelming. It makes buying a wedge of cheese this complicated endeavor. So I started thinking: What would be the most natural, local, ethical cheese possible?

Q. How do people respond to your project?

A. It definitely runs the gamut. Everything from “this is such a great idea” to “this is the most disgusting thing I’ve ever seen.” Overall, response has been pretty overwhelmingly positive, which I didn’t really expect. Maybe it’s New York — we’re pretty adventurous eaters.

Human cheese is initially a pretty shocking concept to most people. In that way its a great conversation starter — people very quickly bring up all sorts of different issues. I’ve had questions come up like, is it OK for a vegan? Is it empowering or exploitative of the woman? Is it dangerous, or actually healthier?

Many people feel uncomfortable because they don’t know the woman, or what she is eating — but how often do you know the cows whose milk make your cheese, and what they are eating? The sustainability question is great, too, a lot of people totally get it, they love that I’m using human extracts to make human food, while others think of cannibalism. But the best is when people are tasting it (or not). There’s something really visceral and instinctual about eating. It’s no longer an idea to play with, but something you have to chew and swallow.

Q. Where did you procure the milk? How expensive was it?

Breast-milk in the freezer waiting to be turned into cheese. (Photo by Miriam Simun.)

A. I used two different sources. One woman lives here in New York, and she very kindly donated it to me — she has been overproducing, filling up her freezer, and was finding it painful to just throw it away. I purchased the milk from the another woman, and she shipped it to me in ice, from Wisconsin. I am working to make a delicious Wisconsin human cheddar. I found both the women on an online marketplace for breast milk — where women regularly arrange to sell and donate their milk. It’s pretty interesting: women set the price of their breast milk depending on if they provide blood work, and also the health of their diet.

I am currently looking for more New York City–based women who are interested in working with me.

Q. You pose some really fascinating questions in the description of your project, quoted below. Can you share what, if any, resolution you came to about each?

As global urban populations increase, developing nations industrialize, and energy, water and land become ever more scarce resources, how will we redesign our food systems to produce healthier, kinder, more sustainably and efficiently produced food?

I’m realizing just how hard it is to create a sustainable food within our current system. The infrastructure we’ve built makes it so much easier to participate in the global system than the local one. One of my goals is to make 100 percent local NYC cheese (especially borough-specific: I would love to see the Manhattan vs. Brooklyn Cheese-Off). To be truly local cheese, it must include not just the milk, but also other ingredients (salt, enzyme, etc.) coming from NYC, as well as all the tools and energy used in the process.

Well, I can source milk from midtown, transport it by bicycle, cook it over a fire — but where do I find vegetarian rennet, or a stainless steel pot manufactured in NYC? And that’s not even getting into the food the woman consumed to make the milk.

As we navigate the complex landscape of technologically modified food production, how do we understand what is natural, healthy, ethical?

As far as “healthier” and “kinder” — I think those are actually a bit easier than the sustainability question. They do require dedication, time, and expense. This is in large part due to the way our food systems have been created and regulated, in which unhealthy and/or unethically produced food tends to be cheaper. But this is our food — the substance we are putting inside our bodies. I can’t think of many things more worthy of our time, money, energy.

What we understand to be natural and healthy changes easily, and is often a sign of the times. What is healthy, exactly: Low fat? Organic? Sugar free? Wild-caught? What is natural also stumps me — I mean, farming is a technology, one of the first — so is only wild-growing food actually natural? That’s pushing it to the extreme, but a useful one to think through our definitions of “natural” and “organic.”

Our ideas about what is natural fluctuate easily — it’s fascinating to watch this with Human Cheese. Many people’s immediate reaction is almost visceral, they exclaim “Ooh!” or “Gross!” Often those very same people within 5 minutes start nodding their head and saying “OK, yeah, that makes sense … ”

Human cheese is in a particularly interesting place — eating human milk after you’re done being a baby, especially from someone other than your mother, is such a huge taboo

— and yet, human milk is arguably the most natural food in the world. Certainly drinking milk meant for other animal’s babies is kind of strange. Unnatural? The great thing about food is that it elicits something visceral — so suddenly you are dealing with these ideas not just rationally, but your body is often responding physically in some way.

The ethics question is a complicated one that I don’t have the answer to. I actually struggle a lot with this issue. Many of people have asked me if I plan on starting a Human Cheese business, or suggest that I do. What would that mean? I am currently producing ethically sourced, boutique human cheese — if it were for sale it would be incredibly expensive.

Does food have to be affordable to be ethical? Affordability, then, often requires large-scale production. But thinking about a large-scale industrialized production in this case, you quickly arrive at the exploitation of poor mothers, who might sell their milk and use formula for their children. An unsettling thought, but how does it compare to the current practice of women in India renting their uteruses to Western couples for in-vitro fertilization, and being confined behind gates for nine months until they deliver the child? These women make the decision to do this, in exchange for around $7,000. Is it exploitation? I’m not sure.

Making human cheese has brought me closer to these questions, even if I still don’t see a clear answer. I hope that for others, deciding to eat or not eat the cheese made from women’s milk might bring these kinds of questions closer to home. As technology makes new uses of the human body possible, and new foods possible, what are we comfortable with? What do we want?

As humanity gains the power to design life on molecular, genetic, and even nano level, how do we, as a species, develop ethics to guide our design of living systems?

This question is a central one in my work. I have just started to scratch the surface of what this means with the people I’ve had a chance to talk to over some cheese. I can say that ethics seem to be pretty heavily tied into our ever-fluctuating idea of “normal.” I’m really eager to continue thinking through these questions over more cheese and wine.

Q. What’s next?

A. A lot! I have a 100 percent pure human cheese in the works. [She currently blends it with goat or cow milk.] It’s a bit tricky, but experimentation is under way. I’m also spending some time this winter seeking out more collaborators — mothers, scientists, cheese makers — food making is, after all, the oldest social ritual and much better done in groups. I also have a series of human cheese tastings coming up this winter and spring. [See her website for more information.]

Q. What was the most interesting or unexpected thing you learned throughout this experience?

A. The culture that exists around making food with breast milk — women make bread, yogurt, ice cream, soup … you name it. I never expected it. Cheese is a bit more complicated, because of the unique properties of human milk. But it’s great to know that I’m not too off-base with human cheese — in some ways, I’m just bringing a niche food product to the mainstream. Kind of like caviar.

For more crazy food news on Grist, check out:

- Bunnies: They’re what’s for dinner

- How to date a vegan

- Worms are the latest sustainable meat

- Organic milk really is better for you

A version of this post was first published at Food + Tech. Used with permission.