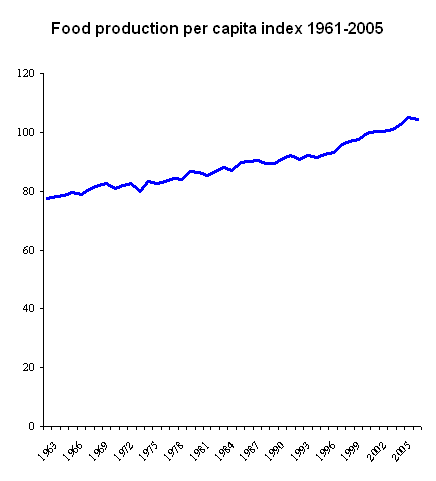

More food than ever — yet hunger persists. Chart: FAOMore than a billion people are hungry worldwide, reports the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations — and the hunger rate has been rising since 2006. Why? The FAO does not mince words:

More food than ever — yet hunger persists. Chart: FAOMore than a billion people are hungry worldwide, reports the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations — and the hunger rate has been rising since 2006. Why? The FAO does not mince words:

Hunger has increased not as a result of poor harvests but because of high domestic food prices, lower incomes, and increasing unemployment due to the global economic crisis. Many poor people can not afford the food they need.

The chart at right underscores that point. Global food production has more than kept up with population growth — there’s been steady growth in per-capita food production. Yet nearly one in six people on the planet go hungry. The problem is complex — but it clearly can’t be solved merely by growing more food. We need economic models that spread income more equitably; and food production models that promote food security within communities.

For agrichemical industry executives, though, such considerations are meaningless. They make money by moving product, not by rethinking economic models. The current global food system, for all its obvious flaws, has been very good to them. Their pitch is simple: Forget about the underlying causes of hunger and strive to grow more food … using our pesticides, fertilizers, and patented GMO seeds.

That evidently, is the main message of a D.C. conference recently put on by Croplife America, the main trade group for U.S. agrichemical interests. (This is the outfit that rebuked Michelle Obama for not using “crop protection” — synthetic pesticides — on her organic garden.)

Now, I have to acknowledge that I was invited to speak at the conference but could not attend, and that two of the fiercest and most cogent critics of the agrichemical industry, Margaret Mellon of Union of Concerned Scientists and Andrew Kimbrell of the Center for Food Safety, were on hand. Croplife deserves praise for inviting high-profile industry critics to its soiree. We need more, not less, blunt debate about how to “feed the world.”

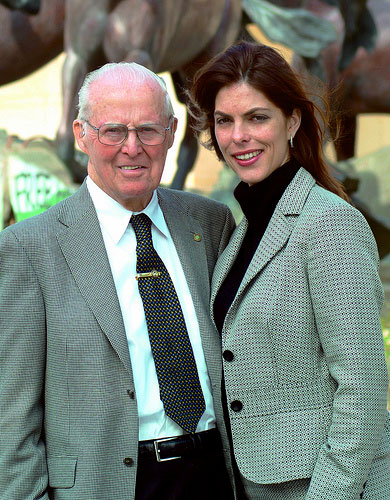

Norman and Julie BorlaugPhoto courtesy AgriLife via FlickrEven so, from what I’ve seen, industrial-ag cant filled the area like pesticides spewing from a cropduster.

Norman and Julie BorlaugPhoto courtesy AgriLife via FlickrEven so, from what I’ve seen, industrial-ag cant filled the area like pesticides spewing from a cropduster.

According to a blog report, Julie Borlaug, granddaughter of Green Revolution architect Norman Borlaug (1914-2009), was on hand to soothe the gathered execs with industry-friendly platitudes. The younger Borlaug, who now serves as a functionary at the academic center at Texas A&M that bears her grandfather’s name, reportedly declared:

It is a production problem … if they cannot produce the food, if we cannot get the food to where it needs to be … it’s not just global justice, it’s global production. If they don’t have the inputs, if there’s no infrastructure, they don’t have any technology, you can’t say it’s an equity problem — it’s a production problem for the people, where they are.

Peel away the Palinesque syntax and you get a straight industry talking point: hunger can only be solved with ever-spiraling doses of “inputs” and “technology”: the very wares being peddled by the assembled executives.

According to the venerable website Farm Chemicals International, Borlaug added a plug for transgenic seeds, aka genetically modified organisms: “My grandfather thought that the only way we will feed all the people in 2050 is through technology, specifically GMOs.”

Invoking her grandfather, whose name is spoken in awed tones among the agrichemichal execs whose products he did so much to promote, gave her argument the aura of finality, of “case closed.” It’s like quoting Jesus Christ to settle an argument among Pentecostals, or Ronald Reagan to quiet some warring Tea Partyers.

But Holy Writ often crumbles under scrutiny. Julie Borlaug’s GMO statement hinges on two assumptions: that ever-increasing yields are needed to “feed the world,” and that only GMOs can deliver them.

Both are dubious claims. For the past half century, billions of dollars in research cash have been poured into increasing yields — and global hunger remains persistent. And GMOs have thus far utterly failed to increase yields.

Rather than adding to a serious debate about the future of agriculture, Borlaug was merely flattering her hosts. I’m glad Mellon and Kimbrell were there to challenge this August assembly — and I wish I had been there, too.