Journalist Ross Gelbspan’s new book, Boiling Point (out in late July from Basic Books), reveals how politicians, big oil and coal, the media, and even activists have fueled the climate crisis — and how we might still avert disaster. This excerpt traces what Gelbspan describes as a corrupt relationship between the Bush administration and the fossil-fuel industry.

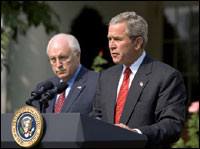

Under the administration of George W. Bush, the White House has become the East Coast branch office of ExxonMobil and Peabody Coal, and climate change has become the preeminent case study of the contamination of our political system by money.

With its heavy bankrolling of the Bush campaign in the 2000 presidential election, the fossil-fuel industry won a victory beyond its wildest dreams. That industry’s long-running campaign of climate-change denial and public deception rapidly became presidential policy. In short order, President Bush reneged on his campaign promise to cap emissions from coal-burning power plants, unveiled the fossil fuel-friendly Cheney energy plan (a fast track to climate chaos), and withdrew the U.S. from the Kyoto negotiations. Then, in a truly Orwellian stroke, the White House altered a U.S. EPA report, removing all references to the dangerous impacts of climate change on the United States.

Apologists for the administration have justified its climate policies by citing politically conservative principles — the withdrawal of onerous regulations, a belief in unencumbered free markets, and the appeal of corporate voluntarism.

In fact, the Bush climate policies have nothing to do with political conservatism. Rather, they represent corruption disguised as conservatism.

Cheney and Bush.

Photo: White House.

For starters, many White House watchers have already documented this administration’s strong ties to the fossil-fuel lobby. The president tops the list of past oil company executives, followed by Vice President Dick Cheney, former CEO of Halliburton, the country’s largest oil-field services firm. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice served on Chevron’s board of directors, while Secretary of Commerce Donald Evans worked for a Denver oil and gas company, Tom Brown, Inc. Philip Cooney, chief of staff for the White House Council on Environmental Quality, was formerly head of the climate unit of the American Petroleum Institute, the main lobbying arm of the oil industry, and a group that is among the most rabid critics of climate science.

Bush’s electoral success, moreover, was heavily funded by big coal and oil. His 2000 presidential win can in large measure be traced to his victory in West Virginia, a state no other Republican presidential candidate had ever won. That win resulted from the substantial support of the state’s coal industry. One coal executive alone, James Harless, raised $275,000 for the Bush campaign in West Virginia, five times more than Al Gore raised there.

Five months after Bush’s inauguration, a West Virginia Coal Association official told a meeting of the organization: “You did everything you could to elect a Republican president. Now you are already seeing in his actions the payback … for what we did.”

That “payback” came in the form of an about-face on a campaign promise Candidate Bush made in 1999 — to repeat nationally what he had done as governor of Texas, imposing a carbon dioxide emissions cap on the state’s coal-fired power plants. In a letter to four Republican senators, Bush said he was backing away from the cap because of the “incomplete state of scientific knowledge of the causes of, and solutions to, global climate change and the lack of commercially available technologies for removing and storing carbon dioxide.”

Particularly pleased by Bush’s flip-flop was Irl Englehardt, chair of the Peabody Group, the country’s biggest coal company. Englehardt had donated $250,000 to the Republican National Committee, and served as an adviser to the Bush-Cheney Energy Transition Team. On May 17, 2001, when the Cheney task force unveiled its new energy plan, it not only called for an expanded role for nuclear power and the opening of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil exploration, but for the construction of between 1,300 and 1,900 new power plants, most of them powered by coal. Within a week of the plan’s unveiling, the Peabody Group — a privately held entity for its entire 120-year life — made an initial public offering (IPO) of shares and went public. Overnight, its stock jumped from $24 to $36.

Exxon, Exx Off

If the administration’s energy plan was covered with the fingerprints of the country’s biggest coal company, its climate policies appear to have been directly dictated by the planet’s largest oil company.

Robert Watson.

Photo: IISD.

Just weeks after Bush assumed office, ExxonMobil official Randy Randol sent a memo to the White House, which was subsequently obtained by the Natural Resources Defense Council through a series of Freedom of Information Act requests. The memo cited a quote from Robert Watson, chair of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: “The United States is way off meeting its targets. A country like China has done more, in my opinion, than a country like the United States to move forward in economic development while remaining environmentally sensitive.” Clearly, Watson’s assertion did not sit well with the memo’s authors, who went on to ask: “Can Watson Be Replaced Now At the Request of the United States?”

ExxonMobil recommended that the Bush administration remove Watson, along with two officials instrumental in producing the U.S. National Assessment on Climate Change, an EPA document that the White House would seek to eviscerate in the spring of 2003. In their place, the oil giant recommended appointing longtime climate “skeptics” John Christy and Richard Lindzen.

Ultimately, the Bush administration did scuttle Watson’s reappointment. But, apparently fearing a major backlash, it decided not to back such vocal contrarians as Christy and Lindzen.

Harlan Watson.

Photo: IISD.

ExxonMobil achieved an even greater success in directing Bush administration climate change diplomacy. Urged on by the company, the White House hired Harlan Watson (no relation to Robert) as its chief climate negotiator. In May 2002, Watson announced that the U.S. would not participate in the Kyoto process for at least 10 years, saying that the White House “wanted no part” of a 2005 international review of greenhouse gas reductions. “The next time we take stock on climate change,” he said, “has been set by the president at 2012.”

In November 2002, in an effort to improve its environmental image, ExxonMobil trumpeted its investment in hydrogen fuel research. But the company’s disingenuous plan was not to derive hydrogen from water, a process that generates no carbon emissions, but to make it from oil and coal — a process that emits so much carbon dioxide as to virtually neutralize the climate-friendly benefits of the new fuel. Two months later, in his 2003 State of the Union address, Bush revealed his own petroleum-based hydrogen initiative. It exactly embraced the ExxonMobil strategy, preserving America’s oil infrastructure at the expense of climate destabilization.

ExxonMobil and the Bush administration have also united in sowing climate change disinformation and deception among U.S. citizens. By 2001, ExxonMobil had replaced the coal industry as the major funder of prominent “greenhouse skeptics,” a handful of “experts” who spout bogus science, raising doubts about climate change to preempt the public’s demand for action. By 2003, ExxonMobil was giving more than $1 million a year to an array of right-wing organizations opposing action on climate change — including the Competitive Enterprise Institute, Frontiers of Freedom, the George C. Marshall Institute, the American Legislative Exchange Council, and the American Council for Capital Formation Center for Policy Research.

The striking success of the fossil-fuel lobby’s disinformation strategy is reflected in two Newsweek polls. The first, in 1991 — prior to the industry’s global-warming misinformation campaign — found that 35 percent of Americans saw global warming as a serious problem. By 1996, that share shrank to 22 percent — despite the advent of far more conclusive science, documenting human-caused global warming.

The usefulness of bogus science was not lost on the Luntz Group, a private consulting firm advising Bush on climate policy presentation. “Americans … believe all environmental rules and regulations should be based on sound science and common sense,” said a Luntz memo. “Similarly our confidence in the ability of science and technology to solve our nation’s ills is second to none. Both perceptions will work in your favor if properly cultivated.”

Sure enough, a new effort by the “skeptics” surfaced in spring 2003. A study by lead authors Sallie Baliunas and Willie Soon at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and published in an obscure journal, Climate Research, concluded that the 20th century is neither the warmest century, nor the century with the most extreme weather, of the past 1,000 years. Both researchers had previously contended that the recent warming was due, almost entirely, to solar variations — a finding long since disproved by peer-reviewed scientific studies.

As it turns out, the report by Baliunas and Soon was funded in part by the American Petroleum Institute. It was also coauthored by Craig Idso and Sherwood Idso, whose Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide has been funded by the coal industry and ExxonMobil.

James Inhofe.

Photo: U.S. Senate.

Predictably, the study was seized upon by Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.), chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, who asserted that this new science showed that natural variability, not human activity, was the “overwhelming factor” influencing climate change. Inhofe received double the campaign contributions from energy companies during the 2002 election than from any other business sector.

In short order, 13 leading climate scientists from the U.S. and U.K. declared in a letter to the American Geophysical Union that the anomalous late 20th century warmth cannot be explained without taking into account the contributions of human activities.

Most telling, perhaps, was another piece of fallout from the Soon-Baliunas controversy that received little news coverage. Three editors of the journal that published the skeptics’ study resigned in protest after they were forbidden from writing an editorial pointing out the methodological errors of the flawed paper by the industry-funded researchers.

While Inhofe attempted to disguise the administration’s fossil fuel-friendly policies under the cloak of “sound science,” the White House worked to scuttle the most thoroughly researched projections of coming climate impacts inside the United States.

The report, known as the “U.S. National Assessment of the Potential Consequences of Climate Variability and Change,” is a meticulously peer-reviewed document, drafted during the Clinton administration. The National Assessment details a range of anticipated, mostly harmful, impacts across U.S. geographical regions and ecosystems.

When previous Bush administration efforts failed to discount and discard the document, the politically conservative Competitive Enterprise Institute, which is partly funded by ExxonMobil, sued the White House Council on Environmental Quality to remove the National Assessment from circulation. In a press release, the CEI dismissed the assessment as “junk science” being used “by global warming alarmists” to hamstring business.

Then, in August 2003, the attorneys general of Maine and Connecticut made an extraordinary discovery. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, they unearthed emails indicating that the White House had secretly urged the private, right-wing CEI to sue it — the White House — in order to have the National Assessment withdrawn.

“It appears that certain White House officials conspired with an anti-environmental special interest group to cause the lawsuit to be filed against the federal government,” said Maine Attorney General Steven Rowe, who complained to the U.S. Department of Justice along with Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal.

Survival of the …?

Stepping back, it becomes clear that the climate crisis represents a titanic clash of interests. It pits the survival, as we know it, of the biggest commercial enterprise in history — big coal and oil — against the survival of the planet and its people. It also pits the fossil fuel industry-dominated Bush administration against the rest of the world.

Oil in a day’s work.

Photo: U.S. EPA.

As of this month, 123 countries have ratified or acceded to the Kyoto Protocol. Several industrial nations have also committed themselves to carbon cuts greater than those mandated by the protocol. Moreover, a substantial number of developing countries that are not required to cut their emissions in the first round of the protocol have begun to do so anyway. Clearly these governments would not be undertaking such massive and wrenching changes if they had any doubt about the climate crisis.

When Bush withdrew the U.S. from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001, he triggered a profound swell of outrage throughout the rest of the world. Given the accelerating momentum of climatic instability — and the willingness of the rest of the world to begin addressing it — the rage against the United States’ indifference to humanity’s common future will only grow worse.

In the early 1990s, when the science was still uncertain, denial and resistance by the fossil-fuel lobby could be excused as a predictable, business-as-usual response. But with the science now so robust, and negative impacts so visible, this behavior is inexcusable. In 2003 alone, 35,000 people died as the result of Europe’s worst heat wave ever, while the World Health Organization reported that climate change is already claiming 160,000 lives annually. If temperatures climb as projected, then the corrupt policies embraced by U.S. industry and government could put the future of civilization at risk.

The industry-driven campaign goes far beyond traditional public relations spin. It has led to the capture of the White House, to gross distortions of science and truth, and to the corporate dictation of public policy. Not that such corruption of the political process by powerful special interests is new to our republic. But the magnitude of the potential consequences is unprecedented.

Our fossil fuels have brought us to a level of abundance and prosperity that was unimaginable a century ago.

Today they are propelling us forward into a century of disintegration.