In the southeast corner of Washington, D.C., the capital of the most powerful nation in history, lies a polluted, neglected neighborhood known as Anacostia. Slated for a grand renewal project centered on the local river that gives it its name, the area stands at the juncture of poverty and opportunity. If plans move forward, it will one day be a showcase of urban design, with revitalized neighborhoods, verdant parks, rolling pedestrian and bicycle paths, and an occasional eagle soaring overhead — in other words, a paradise. Today, Anacostia is more of a nightmare.

Capital improvements are coming to

D.C.’s other river.

Older residents of the area recall a time before incomes and population plummeted, a time before the exodus of the black middle class, a time when the banks of the Anacostia swelled with beaches, bathing, and fishing. But for decades, the story of the river — which is fed by Maryland tributaries, then melds with the Potomac on its way to Chesapeake Bay — has run a different course.

“Washington has always been a tale of two rivers, what you could call the white river and the black river,” says Jim Dougherty of the D.C. Sierra Club, who sits on the national board of directors. While the Potomac has been blessed with plentiful green space, with the Jefferson Memorial and the Marine Corps War Memorial gracing its banks, the Anacostia has been home to the jail, incinerators, and power plants. Activists have continually fought projects that threaten to encroach upon the already degraded corridor — projects that, according to Dougherty, “would never be allowed in western D.C.”

As a result, the place and its people are suffering. Old tires are only the most ostentatious artifacts, with great mounds of litter here and there, and speckles of glass and paper woven among grassy banks. Contaminants affect such bottom-feeding fish as the brown bullhead, which have cancerous growths on their skin and in their livers, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others. With a 100-year-old, combined-use sewage system intended for a much smaller population, the river suffers dozens of overflows a year, during which strong rains bring untreated human waste rushing to its waters.

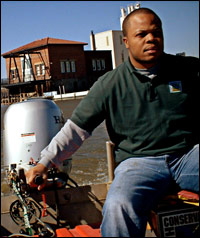

Glen O’Gilvie.

Photo: Ethan Goffman.

“The state of the river has an impact mentally,” says Glen O’Gilvie, president and CEO of the Earth Conservation Corps, which has worked with local residents to clean up the area since 1989. For those who live in the most impoverished portion of our nation’s capital — where violence, unemployment, and lack of opportunity have shrunk the population to well under 100,000, with 38 percent living below the poverty line — O’Gilvie says, “this is one more avenue of hopelessness.”

Six years ago, full-scale plans to revamp the area began in earnest with the signing of the Anacostia Waterfront Initiative, a favorite project of D.C. Mayor Anthony Williams (D). The manager of the ambitious project, Uwe Brandes, explains that it reflects a “new perspective, that rivers can play an important role in the regeneration of cities. Historically they’ve been seen as a way to dump pollution. Now, the national resurgence of the river itself can be the green engine of growth.”

While Brandes’ optimism is reflected by supporters of the city’s efforts, others are more guarded, wondering what price local residents will pay in exchange for an “improved” neighborhood. “Restoration is always a two-edged sword,” says Robert Boone, president of the Anacostia Watershed Society, a community group based in Bladensburg, Md., which bleeds into the blighted urban areas of D.C. He worries that the city’s efforts will end up benefiting those who need them least: “When you start restoring, the poor get forced out. That’s inevitably how our culture works.”

It Runs Through a River

The city’s 25-year redevelopment plan includes creating a network of paths to nearby neighborhoods by restoring green spaces long turned brown. These areas, such as Kenilworth Park & Aquatic Gardens, Kingman Island, and Watts Branch Park (soon to be renamed Marvin Gaye Park), are saddled with trash, frequented by drug dealers, and often contaminated with toxic chemicals. Leaders also seek to create new housing, including low-income options, and to connect isolated neighborhoods with a trolley system. And after a century’s worth of sewer overflows, relief is expected soon: newly installed pumps and valves should result in 40 percent less raw sewage making its way to the river.

Residents get a raw deal.

Photo: Ethan Goffman.

A more complete solution to the sewage problem is some 25 years removed, according to Brandes. Pollutants flow from the Anacostia’s numerous Maryland tributaries, thousands of little capillaries and veins that zigzag just north of the district. “Over 80 percent of the watershed is in Maryland, so automatically there’s an environmental-justice issue there,” Brandes explains, “and that is that the District of Columbia, being downstream, is essentially the recipient of all of this pollution.” From the Anacostia, the combined waste flows onward to Chesapeake Bay, itself the subject of grand and unfulfilled cleanup aspirations.

The Waterfront Initiative is coordinating efforts on the part of community groups, businesses, and local governments to minimize tributary runoff through such techniques as rain gardens, swales, and green roofs. (Known as “low-impact development” and largely pioneered in Maryland’s Prince George’s County, these techniques are now integral to numerous D.C. projects.) All told, says Walter Smith of the advocacy group D.C. Appleseed, “It’s going to be a huge, costly, and a decades-long process.” Brandes agrees: “There’s a lot of goodwill, but there’s a long way to go.”

Despite the long haul, local communities are ready to dig in. “All of the communities that reside east of the river have been advocates for revitalization,” says southeast D.C. resident and Sierra Club D.C. environmental-justice organizer Linda Fennell. “They have always been at the forefront.” Fennell believes the passage of the Waterfront Initiative prompted “an increased level of energy, with communities advocating for better libraries, better parks.”

According to Smith, development plans include significantly more low-income units than projects in the 1990s that displaced low-income residents as western D.C. gentrified, and will also reserve 51 percent of jobs for the local labor force. As Brandes puts it, “We’re attacking this in terms of jobs, in terms of housing affordability, but we’re not limited to that. We’re also attacking it with regard to actual capital-equity participation.” As Anacostia redevelops, existing neighborhood businesses will be drawn into the process. “In other words,” says Brandes, “we have requirements that local, small, disadvantaged businesses in the District of Columbia participate in the redevelopment process directly.”

While D.C. community organizers believe those behind the initiative are seriously concerned with helping the community, they worry that the efforts will not be enough. “Everyone’s saying the right things, and everyone’s heart is in the right place,” says Robert Nixon, chair of the Earth Conservation Corps, “but I haven’t seen a plan yet that involves the entire community.”

Many longtime residents of the watershed are also skeptical, fearing deeply entrenched historical patterns will play out here. Impoverished areas have commonly been denied amenities and granted minimal basic services. As they begin to attract attention and become desirable, environmental degradation is cleaned up and services are enhanced — but swelling housing prices often drive away those who have suffered through the worst years.

Alexandria Lloyd, a resident of Prince George’s County, expresses a common fear. Revitalization, she says, “pushes poor people back into other neighborhoods. Then [rich] people tend to get antsy, taking over neighborhood after neighborhood — and then the gentrification cycle begins all over again.”

Hopes and Fears

The Earth Conservation Corps holds classes, planning sessions, and activities in a historic pumphouse on the river’s banks. Prior to its 1994 restoration, the structure was a blighted shell surrounded by “a snowplow graveyard, with snowplows piled 50 feet high,” says O’Gilvie. Inside, bird droppings reached knee-level, while holes in the floor allowed a glimpse of the brown water below. The degraded pumphouse served as a fine metaphor for the state that has been allowed to fester along the Anacostia. Amid such despair, violence is endemic: the corps suffered a murder each year during its first decade.

Still, the number of participants has continued to grow. Today it stands at 45, and the group’s influence has expanded exponentially. Its first river cleanup attracted 300 people; this year, 5,000 volunteers picked up some 30 tons of trash and debris. The pumphouse, too, has altered dramatically; today it is a tidy brick building full of life. The group’s most prominent achievement, perhaps, is helping to return the bald eagle to the nation’s capital. But as its film Endangered Species asks: if the bald eagle can be restored, why do the youth of Anacostia remain endangered?

During their year of service, corps participants cultivate skills that create future opportunities, from cleaning and operating equipment to learning the ins and outs of computers and boats. O’Gilvie explains that the program seeks to help “solve youth crime and violence, train local residents, and allow them to compete for jobs.”

Indeed, the program claims an 85 percent success rate, based on graduates’ education, employment, and continuing community involvement. As the Waterfront Initiative brings new opportunities, O’Gilvie says, local residents will have the background to fill positions that would once have gone to outsiders: “Skills and training cannot be gentrified.”

His fellow community organizers hope that he’s right. D.C. Appleseed’s Smith fears that the restoration process will be subverted, that it will fail to help those who most need it, that if planners get behind in their goals, “there’s a risk they’ll never catch up.” And the history of the region suggests little margin for error.